Tbilisi - foto M.Lorusso

Giorgi Bobghiashvili, of the European Centre for Minority Issues, spoke to us about national minorities and inclusive policies in Georgia ahead of the next general elections

In October 2016, Georgia will hold the next general elections. How has the Georgian Dream performed in its first mandate, and which problems and challenges await Georgia in 2016? This first analysis focuses on the situation of minorities, a fundamental perspective for a country that has undergone a profound crisis of sovereignty because of ethnic tensions. Indeed, the two breakaway areas of Abkhazia and South Ossetia founded their declarations of independence in the storming and complex years in between the collapse of the Soviet Union and Georgian national independence. It was a period marked by exacerbated nationalisms and micro-nationalisms which at the time resulted in efforts to concretize forms of statehoods short of inclusiveness, where minorities were suspiciously viewed and largely marginalized. As a tragic consequence many citizens were forced to flee to parts of their country where their safety would be ensured (especially Georgians fleeing secessionist areas). The territorial integrity of the newly-born state was badly affected.

Minorities in Georgia today

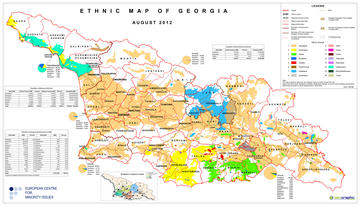

According to the latest census, about 83% of the population identify themselves as Georgians. The largest minority is the Azeri one (about 7%), followed by Armenian (6%) and Russian (1.5%) ones. Other minorities - Abkhazians, Ossetians, Greeks, Ukrainians, Kists, Yezidis, and others - each represents less than 1% of the population. The data do not cover the areas of breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia which do not take part to the national census.

The distribution of minorities varies significantly over the territory, and some regions register a high concentration of communities where they represent the majority. The two areas in which this phenomenon is most visible are the Dmanisi, Bolnisi, and Marnueli provinces of Kvemo Kvartli , which host big Azeris communities, and Akhalkalaki, Ninotsminda, Akhaltsikhe - region of Samtskhe-Javakheti, and Tsalka, province of Kvemo Kartli, traditionally inhabited by Armenians.

Georgia is a member of the Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and its Advisory Committee has recently published the second opinion about the compliance of the government with its obligations.

Since 2009, the legal framework regulating the protection and promotion of minorities’ right has remarkably developed. Georgia approved a Strategy and Action Plan for the integration of minorities, an ambitious plan spanning from education to employment possibilities. A new strategy (the State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration, years 2015 - 2020) was adopted in 2015, and it follows the Human Rights Strategy and Action Plan, dated 2014, which also devoted a part to the promotion of equality for members of minorities. In the same year, the anti-discrimination legislation was drafted and the Body for Equality within the Office of the Public Defender was created. The Ministry for Reintegration, formerly strongly oriented towards the issues of breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia, was renamed the State Minister Office for Reconciliation and Civic Equality, further pursuing the goals of social cohesion, and of a more inclusive society based on civic criteria, regardless ethno-linguistic affiliations. And while Georgian is the official language, the new language law also protects the national languages of minorities. Since 2012, the Criminal Code contemplates discrimination among the aggravating circumstances in crimes.

The incumbent government and voting intentions: an assessment

So much for the overall regulatory framework. But how is actually the situation, how is the Georgian national project evolving, to which extent are minorities part of it, and how can the first term of the Georgian Dream be evaluated?

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso discussed these issues with Giorgi Bobghiashvili, Project Coordinator of the European Centre for Minority Issues . The center is based in Tbilisi, it plays the role of monitoring and advocacy about the situation of ethno-linguistic and religious minorities. To perform its tasks it is in constant contact with various representatives of the civil society, with various state bodies, and is internationally well connected.

The core problems found by the Center with regard to the respect and the promotion of minorities mainly revolve around education, political participation and the perpetuation of patterns of segregation.

As for schooling, the problem lies in the framework of a general deterioration of the education system. Although about 300 schools are able to provide teaching in Armenian, Azerbaijani and Russian, the level of training and updating of teachers remains poor.

Political participation is still influenced by local dynamics, in a complicated context of ethnic but also clan loyalties. The representation and the ability to participate are strongly inhibited by the fact that alternation to power through the elections, and therefore bottom-up accountability, hardly materialize.

As for the dynamics of segregation, poor mobility and exchanges are encouraged by economic stagnation, as well as mixed marriages (which do occur, though, especially between Abkhazians and Georgians, between Georgians and Ossetians) are still greatly hindered by a tradition culturally little trans-confessional. Besides, the media play a fundamental role: Armenians and Azeris tend to watch national or Russian TV programs, therefore being exposed to a different narrative from the majority Georgian.

These critical issues characterized from the very beginning the Georgian national project, and an evaluation of the performance of the incumbent government is, according to Bobghiashvili, mixed. Among positive results of the Georgian Dream, Bobghiashvili lists the efforts towards a general democratization of the decision-making process with respect to the issue of minorities, compared to the times of the United National Movement. Different stakeholders, including the European Centre for Minority Issues, are now involved in government projects, organized civil society is recognized and enabled to play an active role. With the National Movement the entire process was top-down managed, in a not very inclusive way. At the same time, there was - in the transition from one government to another - a loss in terms of professionalism, so what is lacking now is not the political will, but the technical capabilities and the proper background to perform the assigned duties. And this appears to be a factor impacting pretty negatively on the effectiveness of the actions of the current government.

Bobghiashvili also identifies a certain shortage of communicative strategies: the United National Movement - and then President Saakashvili in particular - would visit the regions inhabited by minorities. His visits did not necessarily imply new programs or integration projects, but they made citizens feel less abandoned or alienated from the central government. The Georgian Dream seems to be lacking the capacity to preserve his connection and visibility in the above mentioned regions.

As for the voting intentions of minorities, the outcome is not a foregone conclusion. There is a well established tendency to regard minorities as the stronghold of votes for the majority in office, as the loyalty to the central government is seen as a form of protection for those who feel not sufficiently guaranteed by the state. At present the picture is more complex: the high level of domestic polarization is reverberating in minority communities, who also seem fairly split between the hypothesis of a second term of the Georgian Dream and the search for an alternative.

The competition to win the hearts and minds of this slice of the electorate is open, and the months to come will be critical to influence voting preferences.

To Top

To Top