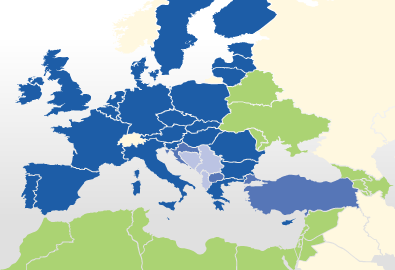

European Union, EU candidates and ENP countries

Countries included in the European Neighbourhood Policy, like the three republics of the South Caucasus and Moldova, are unlikely to join the EU any time soon. Still, according to different rankings, their performance is not so different from that of current candidate countries Croatia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (fYROM) at the time those countries were granted candidate status (2004-2005)

In an effort to avoid new dividing lines, the EU decided in 2007 to create a ‘ring of friends’ by launching the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) with partner-countries as geographically and politically diverse as Ukraine and Morocco. Such an all-encompassing approach has disappointed countries that have long expressed European aspirations and a willingness to be considered for EU membership. Complicating matters further, the visible enlargement fatigue of EU-member countries over involvement in the neighbourhood programme has put a damper on the aspirations of EU hopefuls in the ENP, at least for the near future. In addition, an EU membership offer to the Eastern ENP members may potentially deteriorate relations with Russia, which traditionally considers those countries as part of its sphere of influence. Nevertheless, despite these obstacles, the EU has not only launched the ENP but also presented another policy, the Eastern Partnership (EaP), aimed at cultivating closer relations with Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. These countries have traditionally demonstrated a stronger identification with the EU and openly aspire to membership.

The customary trend of analysis tends to examine the EU’s intentions and policies towards its partners, often blaming the EU for lack of consistency and coherence in its enlargement policies. However, it is also necessary to understand to what extent the European aspirations of the ENP countries are justified. Showing to what extent these countries comply with the EU’s membership criteria is possible by contrasting their democratic and economic progress with the ones of the current candidate countries of Croatia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (fYROM) since the granting of their candidate status.

Frontrunners v/s Laggards...and Those in the Middle

While post-communist countries that are currently EU members have become frontrunners of democratisation and even launched their own democracy promotion programmess, the former Soviet countries are still laggards, mostly paying lip-service to democracy and at the same time striving for EU membership. The Western Balkan countries that received the EU’s consideration for inclusion only in the 2000s have not been among the democratic frontrunners either. However, the ongoing technical and financial support of the EU is supposed to have changed the situation. The prospect of EU membership has seemed to accelerate the process of democratisation being a driving stimulus for domestic reforms. Croatia received its candidate status in 2004 and fYROM in 2005. According to Freedom House, Croatia has qualified as 'free' since 2000, keeping its performance stable. Although it maintained a stable ranking in the period of 2004-2010, fYROM, however, qualifies as 'partly free' according to Freedom House rankings.

Freedom House ranks Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova as 'partly free', with Armenia’s political rights index actually deteriorating within 2004-2009 and worsening in 2010. Following Rose Revolution euphoria, Georgia’s democracy ranking improved in 2005, then again deteriorated in the years 2008-2010. In the period of 2004-2010, Moldova kept a stable 'partly free' ranking, while Azerbaijan kept the status of 'not free'. In this group, only Ukraine has improved its ranking, moving from 'partly free' to 'free' from 2006 onwards. Other democratic indices such as the Bertelsmann Transformation Index and Polity IV give similar scores to these countries, with Ukraine and Moldova being the frontrunners, Georgia and Armenia the runners-up, and Azerbaijan the democratic laggard.

Although usually an elusive concept, rule of law has become the flag of democracy promotion projects and target countries are often judged by their adherence to what is usually measured in levels of corruption and independence of the judiciary. None of the considered ENP countries, with the relative exception of Georgia, performs well in terms of reducing corruption according to the Corruption Perception Index. Azerbaijan has regularly received the worst evaluations from experts and Armenia has been the only one whose position steadily worsened between 2004 and 2009. Georgia, ranked much lower than Armenia in 2004, improved in 2008, jumping ahead of Moldova, Ukraine, and fYROM with evaluations on the level of those of Croatia. While, according to the CIRI judiciary independence index, the judiciary is characterised as 'not independent' in all ENP countries, the judiciary in Croatia and fYROM are considered to be 'partially free'. Similar evaluations are given to all these countries for the handling of human and minority rights.

After the break-up of the Soviet Union, post-communist and post-Soviet states rapidly distanced themselves from the planned economy model and opened their markets to intensive trade with the West, proving that economic reforms were easier to implement and follow than democratic ones. The Index of Economic Freedom (IEF) classifies Armenia as 'mostly free', giving it a stable ranking from 2004 to 2010 and placing it close to Macedonia and well ahead of Croatia. Georgia progressively improved its IEF ranking, moving from mostly 'unfree' in 2004 to 'mostly free' in 2010. According to World Bank rankings, among the countries evaluated, Georgia seems to be the easiest place to do business, with Azerbaijan yet again at the bottom of the list.

Interestingly, the ENP democratic frontrunners, Moldova and Ukraine, show significantly worse results in economic freedom and in doing business than their less democratic counterparts of Armenia and Georgia. Thus, there seems to be a negative correlation in these countries between progress in democracy and progress in economic freedom, as the cases of fYROM and Croatia also confirm. The exception in this case is Azerbaijan, which shows stable low progress in both democracy and economic freedom.

In or Out?

The ENP Strategy Paper identifies the South Caucasus as a region that should receive ‘stronger and more active interest’ than it currently does. After the Orange Revolution, Ukraine has become the ENP favourite of the EU, receiving more funds and technical development assistance. Though, not showing similar democratic progress, Moldova, due to its kinship with the EU member, Romania, also claims its place within both cultural and political Europe. Inclusion of these countries into the ENP marked an step forward in their relations with the EU, but at the same time disappointed them because it shut the door to EU membership opportunities for them in the near future. The disappointment was especially strong for those who openly included EU integration in their foreign policies. However, how justified are these claims for membership opportunity? Although the five post-Soviet countries are behind the current candidates on the democraticy front, some of them are either at the same level or, indeed, ahead in terms of their economy.

The progress of the candidate countries during the years considered is rather limited but they do show better results in terms of democratic criteria. While their scores improve for some components of the rule of law and democracy standards, their results in terms of economic freedom and doing business are more modest. On the other hand, the progress in terms of economic freedom indicators of the ENP countries discussed here is rather high, unlike the progress on their democratic performance. However, the most interesting finding remains the small difference between candidate and ENP countries according to most of these indicators, in particular if comparisons are made between the current standing of the ENP countries with Croatia and fYROM at the time the latter were granted candidate status (2004-2005).

Taking into consideration the EU’s enlargement reluctance and low probability of any fast-track accessions, the ENP countries need to show substantial progress in both political and economic criteria to somehow increase their chances. At the same time, the EU needs to more clearly define its enlargement criteria and borders in order to avoid rhetorically binding itself to membership promises and accusations of double standards.

*Nelli Babayan is a PhD Candidate at the School of International Studies, University of Trento (Italy) and co-editor of Interdisciplinary Political Studies

To Top

To Top