The train for Budapest (Photo André Cunha)

The journey from Syria to Europe, along the Balkan route. In Hungary: apartheid and solidarity. Third Episode

“Where can I throw this cigarette butt?”, asks a thoughtful migrant, to our surprise.

“I don't know. I'm not from here either”, I answer.

“I'll throw it there, in the rubbish bin.”

“I've just thrown one on the ground”, says one of the Szeged inhabitants there with us in the forecourt of the station where the police have just left about 60 migrants to wait for the first train at dawn, destination Budapest. It leaves at 4.36, in about 7 hours.

After throwing his cigarette butt in the rubbish, the man comes back, breathes, fills his lungs and begins to talk. And he doesn't stop – no need for questions.

“I left Damascus a month ago, at the beginning of June. I went through various checkpoints on my way by car to Beirut. I took a plane to Turkey, then a boat to Greece. I went through Athens, Thessaloniki, Polikastro and Evzonoi. We crossed into Macedonia on foot. In Macedonia we went on bicycles, on foot and by train. In Serbia we also went on foot and by train, and by car as well.

And then on foot, until the Hungarian police caught us. We've used every possible means of transport to get here.

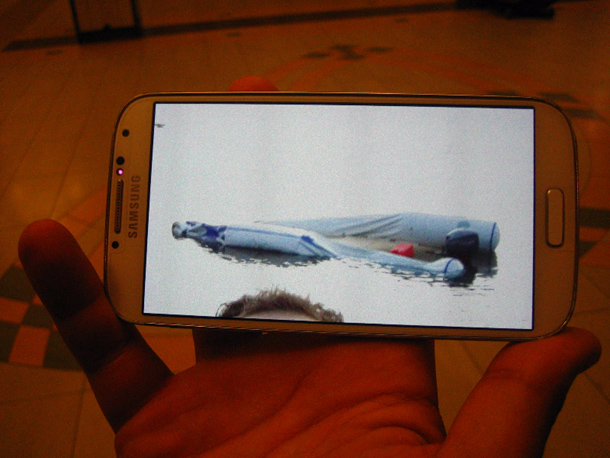

To get into Greece by Turkey we went by boat, leaving from a beach near Izmir and landing on the island of Kos. I paid 900 dollars, but other refugees arriving later paid up to 1,500 dollars. We were really scared. They took us late at night. They told us to stay in complete silence, the children mustn't cry. We couldn't even light a cigarette. While on the beach we put on lifebelts, then got into one of those inflatable rubber dinghies that could carry a maximum of 30 people – it was written. We were 46 adults and 4 children. When we'd all got into the boat we asked the traffickers, “Which of you is coming to steer the boat?” And they answered we had to steer it ourselves. None of us knew how to. They gave us an old cell phone and from the hill above, where they were watching us, they told us on the phone, bit by bit as we went forward, “Left, right”. Over an hour later we arrived on the beach at Kos. It was a miracle, we were so happy, we were in Europe! Do you want to see the video? I've got it here on my smartphone, look...”

He shows us the last part of that video-log-book: in the first light of dawn the boat arriving on the European beach. Then some photos: a view of the beach strewn with hundreds of lifebelts left by migrants before them and a selfie of his enormous smile with the half-wrecked boat in the background.

“The boat began to leak towards the end, then, the last miles, it nearly sank”, he continues.

Here at Szeged a bicycle goes past, then one of the late night trams, Number 2, headed for Europa liget, Europe Park.

“But the worst was yet to come, in Macedonia, with the mafia and traffickers. I think they're in collusion with the police. We were assaulted in the mountains. But a funny thing happened: at a certain point our group, of about 10, had to buy bicycles in order to go on. We all bought them, at 125 euro each. Then, as we were ready to leave, one of the group said, “I can't ride a bike!” Do you know what happened then? We spent half an hour teaching him and he learnt in a hurry, so we continued our adventure. He had learnt to ride a bike in half an hour!

In the end we got to Hungary. We paid 500 euro to the traffickers in Serbia to take us across the border, and if we arrive in Vienna we'll have to pay a further 1,000. It's very expensive, but it's worth it. Do you know how much I've paid so far? Nearly 3,000 euro. One Syrian managed to buy a false passport in Greece from a Greek who looked like him. Do you know how much it cost him? 9,000 euro. A ticket for a direct flight to Germany! It was expensive, but that way was also much easier. I would have done the same...”

I have a dream

His phone rings. It's a friend in Damascus. He doesn't answer but asks us to excuse him for a moment while he tries to ring home – since his friend managed to call, maybe the electricity is on in Damascus. In fact he only manages to talk to his family when he finds a wi-fi connection here in Europe and when their electricity is on in Damascus – a rare coincidence. He hasn't spoken to his mother for three days; she doesn't know the story of the last border, and she won't get to know it this time either.

“Last night we crossed the border on foot to where a car was waiting for us. We'd just set off when a man came up, dressed in plain clothes, who pointed a pistol at the head of our driver, a Serb. They shouted at each other. We were very scared. Then the police arrived and took us to the police station. It was 11 in the evening and they didn't give us anything to eat until 1 in the morning: bread, a bar of chocolate and a sweet. Then they took finger prints of all our fingers. At the police station I really was scared. One policeman had hit another Syrian refugee on the head and shouted, 'I'll put you in prison!' And my Syrian friend shouted at the policeman, 'I'll report all you're doing to me to the United Nations!' We are trying to escape war and violence, we don't want to have to face more violence. They didn't treat us with humanity. I'm only a human being”.

Before lighting another cigarette, he offers us one. That packet cost him 5 euro, sold to him by a policeman at the police station. Outside a packet costs 3 euro. With his cigarettes in a bag he holds tightly against his belt, he has a cigar he promised himself to smoke when he reaches his final destination. There had been two cigars, the first he smoked when he set out from Damascus.

“I couldn't stay in Syria. A cousin of mine was kidnapped at a police checkpoint. There's no future. I had a towel and table cloth factory at Duma, near Damascus, when I was younger [he's now about 30 years old]. I fell in love, got married; a mistake. Then the war came and destroyed the factory. But from 2011 I was able to take a University course in factory management while I worked as an administrator of a bank. I didn't want to leave Syria. My mother's very sad – I'm the only male child. Now she and my father are alone with my sisters. But there's no solution – I can't set up a new business in the middle of a war, in a country under embargo. I want to build a new future, in Europe. In 4 or 5 years I want to have Swedish citizenship”.

He pauses and tries to talk to his mother, in vain.

“Do you like reading? You should read one of the last books I read before leaving Syria. I read it in one night, straight through. I couldn't stop. The writer is called Moustafa Khalifa and the book Al-Qawqa (The Shell. My years in Syrian prisons - the fictionalised diary of Khalifa's experience in the prison of the Hafez-al-Assad regime, from 1982 to 1994). It's incredible! The story of a man who'd studied film in Paris; on returning to Syria he was arrested by the political police. He was in prison for twelve years at Palmira. It's the true story of a man who is now in exile. You really should read this book”.

He stops for a moment to go and throws his cigarette butt in the rubbish.

“Do you know something? I've lost weight in this month. Look at my belt - I've tightened it by two holes. Sometimes I don't eat much because I'm scared I won't find a decent toilet to use... I prefer to eat Snickers and drink Red Bull to have more energy. Hey, do you want to see how fat I was? I have some photos on my phone of me when I was still in Damascus. Look at this, at my friend's wedding, all well dressed in jackets and ties. I really am thinner, aren't I? This trip is like a diet and sport at the same time! [loud laughs] We have to keep our sense of humour and optimism. I have a dream. I will make it!

Hungarian solidarity

“What's your name?”

“Mohammed.”

“I'm Balázs.”

In this summer cut through with barbed wire, Balázs Szalai has surely spent more hours at the Szeged train station than he has at home. A thirty-year-old freelance journalist, working with Radio Mi and also an activist with Migszol, a Hungarian movement for solidarity with migrants, Balázs had not heard all Mohammed's story because that night in June he was so busy he never had time to stop.

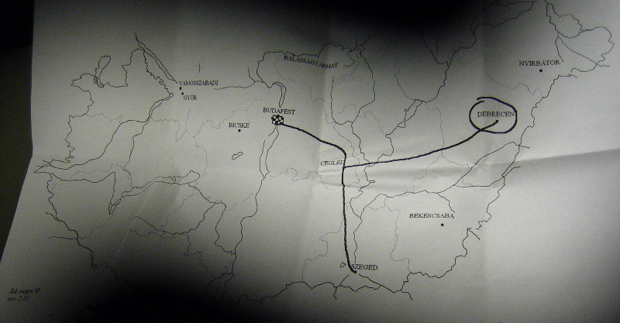

It was Balázs who, with a growing group of local volunteers, organised the food collection for the 60 or so people, including a dozen children, who were there counting the hours till the first train to the future. It was Balázs who, always with a smile, tried to explain what he knew to those men and women, identified by a green bracelet and holding a letter from the police saying, in Hungarian, that they had 3 days to report to Debrecen, the biggest refugee camp for asylum seekers in the country, a camp then on the point of exploding.

Some of them had also received an A4 paper, a black and white photocopied map of Hungary, with Szeged, Debrecen and Budapest marked. But hardly anyone takes any notice of the official recommendation to go to the camp indicated; they all intend going to Budapest then Vienna, following the Danube.

The night progresses, the column of mercury falls to a point between 10 and 15 degrees. The station master tells Balázs that despite the unusual drop in temperature, it was necessary to close the station and move “all those people into the road.” Balázs' answer came back, “and if all these people were here because of an earthquake or another emergency?” But the response is dry and incontrovertible: “This is not an emergency.” When the police arrived theoretically to carry out the closing, Balázs stood there with his smartphone filming it all.

That phone and Balázs' eyes formed a kind of wall against inhuman acts, sometimes undertaken with an excess of zeal. He was the only wall there to defend those people. And that night, unlike many others, the station didn't close and the children didn't have to sleep in the open.

The old want to live too

In the atrium the clock has already struck midnight. Fatma and Ahmed are dozing in their parents' arms – a family who have fled from the region of Kamishlié in Syrian Kurdistan, very close to the front line of ISIS. The whole of that night two-year-old Fatma was the only one we heard crying, and that only for a second. Some people are sleeping on the floor, wrapped in a blanket or in a sleeping bag, dirty and frayed from the journey. Some fall asleep sitting against one of the pillars supporting the panel showing departures, where we can see that the first train in the morning is the one everyone's waiting for, the 4.36 to Budapest. Others sit on the stairs, chatting, passing the time on internet or with games on their phones. Every so often someone manages to call their family, on the other side of the war, and we suddenly hear a glowing voice, at low volume, a timid explosion of happiness, in an undertone. On the floor above, the same scene is repeated. If you remove the context, they just seem like a group of travellers who've missed the last train and have to wait for the first one in the morning. But since the context is there, we are intrigued by a lady alone with a stick. She's dozing on the bench, she'll be between 60 and 70. How on earth did she manage to get here? “The old want to live too”.

Three thirty in the morning. There's only one of the group of volunteers left – Balázs, one human being holding a ten litre saucepan of tea for another sixty human beings who would otherwise be having tea in their own homes, if they still existed, in those places where tea is a daily routine. The tea of Szeged could hardly rival the tea of Damascus, Kabul, Sulaymaniyah or Kamishlié, but its flavour will last in these people's memories. They fill the plastic beakers and Mohammed with his companions take them round the group. In the corner, there's someone still in the arms of Morpheus. Mohammed turns to a rather grumpy railway worker who's trying to carry out the order to close up, and offers him a beaker of tea. He too is “just a human being”. He refuses, with the same austere tone he then uses to inform us he had to “put them all in the last carriage of the train”.

Separate carriages

“The train for Budapest is due to leave from platform 1”, announces the loudspeaker.

We've had our last cup of tea. There's the sound of preparation for the umpteenth departure. The sixty people we spent the night with get settled into the various compartments of the last carriage. There's room for everyone – not yet one of those dramatic scenes later to be seen in Macedonia of men, women and children squashed into carriages like matches into a box that's too small.

At the last minute a young Hungarian arrives, dragging her case along the platform, a case much bigger than any of the backpacks the migrants have to carry their whole life in. She starts to get into the last carriage as the train is about to leave, her companion trying to load the case, but they are stopped by the railwayman's imperious voice: “Not there, in the other carriage!” She goes along thirty metres before climbing on board. For this 4.36 train to Budapest, the railwayman seems the one to decide, not the passenger, who he/she will sit next to – a fellow traveller or “another”.

Migrants in the end carriage, Hungarians, Europeans in the other three, up front.

Mohammed waves from his seat while others lean out to shake hands with me, Móni Bense, the teacher and translator accompanying me on this journey along the new wall and, clearly, Balázs Szalai smoking his last cigarette of the night, the first of the morning.

The whistle sounds, the arm-waving accelerates, smiles multiply. “Goodbye”, “Thank you!” “As-salamu alaykum!”

Head bent, the railwayman turns his back to the departing train, but Balázs' gaze stays there, following those arms waving on the horizon. The journey continues, for those who leave and those who stay. Mohammed and Balázs promised to keep in touch on Facebook, wall-to-wall.

To Top

To Top