copyright: Kai Vöckler

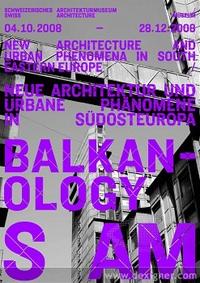

With his eclectic studies, urban researcher Kai Vöckler, curator of the exhibition Balkanology: New Architecture and Urban Phenomena in South-eastern Europe is trying to accomplish a "mission impossible": to prove that a participatory and sustainable urban life is also possible in South-eastern Europe. First part of an interview

The exhibition Balkanology: New Architecture and Urban Phenomena in South-eastern Europe explores the urban dimension of socio-political transformation in South-eastern Europe. Why did you choose ex-Yugoslavia and Albania and what do you want to suggest through this title?

War is the only point that comes to mind for most people in Western Europe - but also in new EU member countries like Romania or Bulgaria - when they think about the Western Balkans. On the contrary, I think it is extremely important to have a closer look at what's actually going on there and I focused on the countries I know best, thanks to my background as programme manager for Archis Interventions, an NGO working on urban development in South-east Europe.

Concerning the title, we debated about whether to use the term Balkan or not because in the German language, it has quite a negative connotation. Anyway, this term pops up every time one deals with the region, so we decided to use it very offensively to break its cliché and to show the real driving forces behind this "mess." Moreover, I wanted to avoid an "exotic" approach. I invited many local colleagues - architects, planners, architecture historians - to participate in the exhibition and to show how professionals are tackling urban development in South-eastern Europe. In this sense, I thought that the term Balkanology could helpfully suggest a more "scientific" point of view.

Introducing the exhibition, you say that you tried to avoid giving an overall image valid for the whole region. Does Balkanology suggest that it is possible to organise different urban processes under the same concept, something like "Balkan architecture?"

In the exhibition there is an architecture section and an urbanism one. We addressed architecture separately, focusing only on Yugoslavia because Yugoslav architecture was extremely high-level, even if it is mostly unknown and not documented. But Yugoslavia also reached very high standards in planning and it exported a lot of planning, as you'll see if you go to the so-called "non-aligned countries" in Africa or Asia. Look at the the extension of Calcutta (India) in the '60s: it was Yugoslav planners who did it. To let Western architects understand the so-called "turbo-urbanism," it was necessary to show them that in the socialist time, there was architecture as elaborate as there is now by looking at social housing in Croatia and Slovenia. I would say it's better nowadays than what we built in Germany!

When the breakdown happened, Yugoslav countries suffered two transformations at the same time: both war and the collapse of the socialist system. This meant huge refugee flows and the complete crash of state sovereignty. Here is the starting point of what we call "turbo-urbanism." In the exhibition, we tried to show why this could happened in the middle of Europe in a country that had such an elaborated architecture and planning culture.

At the same time, I wanted to avoid giving a unique interpretation valid for the whole Western Balkans. My aim was to show the different positions in urban development and the concrete solutions adopted by people working in the region. The selected research presents how people deal, in different ways, with such urban development. As nobody believed before, in Montenegro or, even more astonishing, in Tirana, they are very much ahead now in these processes: Albanians have been doing a lot since 1997-8 (when the state collapsed because of the breakdown of the Pyramid Schemes) and Tirana is now really an example of how you can deal with informal settlements and how you can improve your city.

You mentioned that some collaborators see some positive aspects. Which are they?

For example, Srdjan Jovanovich Weiss sees this process as a kind of improvisation, how people use their creativity in uncertain situations. He tries to look at what you can learn as an architect from this phenomena. Anyway, I am more critical. I consider these problems not regarding aesthetics. I am not interested in discussing with people whether they like having a mix between a Victorian, American or whatever free-style architecture. What really matters is looking at the level of cities' development: what happens if the state collapses and building laws are not enforced?

What happens? How does it come to turbo-urbanism?

In the case of Kosovo, Kosovo Albanians - circa 90% of the population - had been oppressed and kept out of all official institutions since 1981. When the NATO troops went in 1999 and the Serbian military (together with some of the Kosovo Serbs) left the country, Kosovo Albanians had to install the local institutions again. In post-war situations, institutional building often takes too long. While huge flows of migrants returned to the city, people from rural areas moved to the urban centres and a lot of Western European countries repatriated refugees. Consequently, Pristina exploded: the population at least doubled, if not tripled, in about one or two years. In response to a huge lack of housing, everybody tries to build.

Then, building a house is the only way to make money in post-war contexts: a very big market grows in which the building mafia is active too. UN authorities, who officially had the necessary powers, avoided tackling this very sensitive question because they didn't want any kind of political problems. Especially after 2001, when the director of the city department for urban planning of Pristina, Rexhep Luci, was killed because he touched on this theme, everybody stopped even talking about it. The disaster in Pristina is that, since the war, 75 % of the urban fabric has been destroyed by illegal building and you can't blame people doing it because until 2006, it was impossible to get a building permit. As a result, now we are facing extremely problematic aspects: escape routes are blocked, safety standards are not respected in the city, public ground is occupied, there are big social conflicts between neighbours because people have blocked the windows by building, and so on...

When we started our initial project with Kosovo architects and planners in 2005, everybody told us that it was a "mission impossible." Nevertheless, we are now working with the municipality and things are improving. Change is possible, but it requires political will. Also, the society itself has to decide that it wants to change the situation. Most Kosovo Albanians have been abroad for a long time as migrant workers or refugees. They know very well the way Germans do it and if you talk with them, a lot of them say it should be like in Germany. My reply is that in Kosovo, they have to find their own way of dealing with it: it's a kind of debate going on within the society about what and how we want to live.

So, you are saying that there is a chance for civil society at the domestic and international level to change things. Which tools can be used? You mentioned raising social awareness through public debate about these issues. What else?

In our opinion - which is quite unusual for planners - a regulatory plan, even if necessary of course, is not enough if you cannot enforce it. Politicians usually move if they are under public pressure, thus what we actually do is raise public awareness and bring the issue into public discussion. We combine it with media strategies, and it is working. In December 2007, when the elections for the mayor took place in Pristina, all three candidates considered city development as the main issue for Pristina. After the new mayor was elected, he directly asked us to cooperate with the municipality, developing strategies to improve the situation. For example, we established an advisory board of independent people - planners, but also respected people from society - to which people can go to ask for support and advice in the process of legalisation. In March, we are working with them on the concept of transparency, which is also extremely important since Kosovo is highly corrupt and you need to make such processes as transparent as possible in order to avoid as much corruption as possible.

Go to the of the interview

To Top

To Top