Gjirokastër, the bazaar built of stone

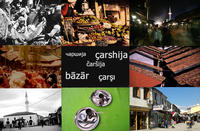

Kadaré defined it “the steepest town in the world” – Gjirokastër, in Southern Albania, on the border with Greece. Its çarshija also stretches upwards on sloping streets. Its architecture, although preserved over the centuries, has been slow in developing a new commercial life

“Gjirokastër is a steep town, maybe the steepest in the world”, wrote Ismail Kadaré in “Story on Stone”, one of his master pieces based on his childhood, spent in this town in Southern Albania. Steep too is the town’s Ottoman bazaar, rising and falling continuously following the flowing rhythm of the cobblestones and the rooftops made of limestone slabs.

The bazaar is a combination of shades of grey and the luminous white of the recently restored facades. Since Gjirokastër became a Unesco Heritage Site in 2005 the bazaar has begun to recover its identity, even though there is much left to do.

Gjirokastër is a town made up of two adjacent urban centres, the historical one which climbs upwards and the more recent one down in the valley, built after the Second World War. Living together is not always easy, with conflict between epochs which blend and clash, endangering the equilibrium of one of the most precious historical and cultural sites in the Balkans.

The new buildings, begun in the first years of the Hoxha regime, not only brought many people from the surrounding countryside to live in town, but also attracted the owners of old stone dwellings in the historic part, to the new, more comfortable apartments in the suburbs. Shops in the bazaar closed down and the old centre depopulated. With this the bazaar also died, even if its architectural framework has been very well preserved, thanks to the town being proclaimed a Museum in the 60s and the centre for a number of cultural activities at a national level. The fact that it is the birthplace of Enver Hoxha and the writer Ismail Kadaré has further contributed to the appreciation of its architectural value.

The ancient bazaar

Mobile phone sellers, a dressmaker, a souvenir shop, others selling kilims (carpets), some cafes and heavy traffic – that’s all that remains of the ancient bazaar. It is still situated at a nerve centre, a crucial junction between different quarters, and it pays for it in terms of traffic. Some NGOs, recently interested in revitalising the town, have repeatedly pointed out this problem to the local authorities who have postponed dealing with the issue until a bypass road can be built.

Few people stop to shop in the bazaar or even have a coffee along the street. “The bazaar is dead, it’s gone. It’s all moved down to the valley. They should bring some institution up here to get people to come. The University, for instance; students would liven it up”, comments an elderly lady selling qilim (traditional carpets).

This idea has been around for some time. But it seems easier to say than to do. “It’s difficult to reconcile the historical architecture of the exterior and interior of the bazaar buildings with a modern use like that of a University,” says Elenita Roshi, deputy director of the Organisation for the Conservation and Development of Gjirokastër. Most structures are first and second category heritage buildings, which means there is a ban on altering many of their features.

Restoration issues

Nor is it easy to embark on restoring the buildings, a crucial step which would open the way for revitalisation. The particular architecture of an Ottoman nature – which is mainly the result of cultural exchanges and trade among the Ottoman economic elite in this part of the world – requires extremely specialised technicians. Few now know how to repair the roofs with stone slabs, while the interiors, lined with decorative inlay, need specialised craftsmen many of whom have latterly emigrated to Greece.

It is also true though that being a Unesco Heritage Site has brought financial contributions for the renovations – in particular from the Packard Humanities Institute and the European Union – and, thanks to the various donors, teams of architectural students coming from all over Europe have been organised. But the process is still at the start and the results scarcely visible. What are most worrying are the uncoordinated efforts at reconstruction. Here and there the colour of the stone slabs has been substituted by the red of common tiles. “The roof was falling in, I asked the authorities, but no-one helped me. The stone slabs are very expensive. I would have used them if I could have afforded them”, says an elderly man.

Paradoxically the first obstacle to be overcome is not to do with funding, but is the question of the ownership of the abandoned buildings which are to be restructured. It is in fact necessary to obtain the consent of all owners that, for each building, are multiple and scattered around the world. “We are presently collecting the signatures of the Kokolari family of 70 members to be traced in Gjirokastër, Tirana, England, the United States and Canada”, explains Elenita Roshi.

The negative repercussions of the Albanian situation in the 90s have been felt in this town too. In 1997 during the political and economic crisis the land registry office was set on fire and the NGOs responsible for revitalising the bazaar also have the difficult role of dealing with the legal problems among the owners.

Tourism and the bazaar

Something, however, is moving. Tourists come from Northern Europe, Italy and Greece but the number coming from other Balkan countries is growing as well. Some inhabitants are thinking of converting properties lying on the bazaar’s main thoroughfare into Bed and Breakfast accommodation. And in one side street a craftsmen’s organisation has just been formed with the aim of encouraging emigrants to return (mainly from Greece) and give them economic support.

Amid the neglect and the traffic, in a café, three or four men sing in a polyphonic chorus – this is also part of the Unesco Cultural Heritage – emitting a combination of guttural and high-pitched sounds, following a precise ancient musical procedure: improvised music, characteristic of this town. An ancient song which has survived, but also a glimmer of hope for what the bazaar will become when the craftsmen, traditional vendors and, naturally, the customers return.

Tag: Seenet

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Gjirokastër, the bazaar built of stone

Kadaré defined it “the steepest town in the world” – Gjirokastër, in Southern Albania, on the border with Greece. Its çarshija also stretches upwards on sloping streets. Its architecture, although preserved over the centuries, has been slow in developing a new commercial life

“Gjirokastër is a steep town, maybe the steepest in the world”, wrote Ismail Kadaré in “Story on Stone”, one of his master pieces based on his childhood, spent in this town in Southern Albania. Steep too is the town’s Ottoman bazaar, rising and falling continuously following the flowing rhythm of the cobblestones and the rooftops made of limestone slabs.

The bazaar is a combination of shades of grey and the luminous white of the recently restored facades. Since Gjirokastër became a Unesco Heritage Site in 2005 the bazaar has begun to recover its identity, even though there is much left to do.

Gjirokastër is a town made up of two adjacent urban centres, the historical one which climbs upwards and the more recent one down in the valley, built after the Second World War. Living together is not always easy, with conflict between epochs which blend and clash, endangering the equilibrium of one of the most precious historical and cultural sites in the Balkans.

The new buildings, begun in the first years of the Hoxha regime, not only brought many people from the surrounding countryside to live in town, but also attracted the owners of old stone dwellings in the historic part, to the new, more comfortable apartments in the suburbs. Shops in the bazaar closed down and the old centre depopulated. With this the bazaar also died, even if its architectural framework has been very well preserved, thanks to the town being proclaimed a Museum in the 60s and the centre for a number of cultural activities at a national level. The fact that it is the birthplace of Enver Hoxha and the writer Ismail Kadaré has further contributed to the appreciation of its architectural value.

The ancient bazaar

Mobile phone sellers, a dressmaker, a souvenir shop, others selling kilims (carpets), some cafes and heavy traffic – that’s all that remains of the ancient bazaar. It is still situated at a nerve centre, a crucial junction between different quarters, and it pays for it in terms of traffic. Some NGOs, recently interested in revitalising the town, have repeatedly pointed out this problem to the local authorities who have postponed dealing with the issue until a bypass road can be built.

Few people stop to shop in the bazaar or even have a coffee along the street. “The bazaar is dead, it’s gone. It’s all moved down to the valley. They should bring some institution up here to get people to come. The University, for instance; students would liven it up”, comments an elderly lady selling qilim (traditional carpets).

This idea has been around for some time. But it seems easier to say than to do. “It’s difficult to reconcile the historical architecture of the exterior and interior of the bazaar buildings with a modern use like that of a University,” says Elenita Roshi, deputy director of the Organisation for the Conservation and Development of Gjirokastër. Most structures are first and second category heritage buildings, which means there is a ban on altering many of their features.

Restoration issues

Nor is it easy to embark on restoring the buildings, a crucial step which would open the way for revitalisation. The particular architecture of an Ottoman nature – which is mainly the result of cultural exchanges and trade among the Ottoman economic elite in this part of the world – requires extremely specialised technicians. Few now know how to repair the roofs with stone slabs, while the interiors, lined with decorative inlay, need specialised craftsmen many of whom have latterly emigrated to Greece.

It is also true though that being a Unesco Heritage Site has brought financial contributions for the renovations – in particular from the Packard Humanities Institute and the European Union – and, thanks to the various donors, teams of architectural students coming from all over Europe have been organised. But the process is still at the start and the results scarcely visible. What are most worrying are the uncoordinated efforts at reconstruction. Here and there the colour of the stone slabs has been substituted by the red of common tiles. “The roof was falling in, I asked the authorities, but no-one helped me. The stone slabs are very expensive. I would have used them if I could have afforded them”, says an elderly man.

Paradoxically the first obstacle to be overcome is not to do with funding, but is the question of the ownership of the abandoned buildings which are to be restructured. It is in fact necessary to obtain the consent of all owners that, for each building, are multiple and scattered around the world. “We are presently collecting the signatures of the Kokolari family of 70 members to be traced in Gjirokastër, Tirana, England, the United States and Canada”, explains Elenita Roshi.

The negative repercussions of the Albanian situation in the 90s have been felt in this town too. In 1997 during the political and economic crisis the land registry office was set on fire and the NGOs responsible for revitalising the bazaar also have the difficult role of dealing with the legal problems among the owners.

Tourism and the bazaar

Something, however, is moving. Tourists come from Northern Europe, Italy and Greece but the number coming from other Balkan countries is growing as well. Some inhabitants are thinking of converting properties lying on the bazaar’s main thoroughfare into Bed and Breakfast accommodation. And in one side street a craftsmen’s organisation has just been formed with the aim of encouraging emigrants to return (mainly from Greece) and give them economic support.

Amid the neglect and the traffic, in a café, three or four men sing in a polyphonic chorus – this is also part of the Unesco Cultural Heritage – emitting a combination of guttural and high-pitched sounds, following a precise ancient musical procedure: improvised music, characteristic of this town. An ancient song which has survived, but also a glimmer of hope for what the bazaar will become when the craftsmen, traditional vendors and, naturally, the customers return.

Tag: Seenet