Selective abortion: in Montenegro is still alive

Sex-selective abortion and son preference are still alive in Montenegro. We talked about that with Diana Dubrovska, a young Latvian anthropologist interested in sex, gender, and sexuality issues who is teaching at Riga Stradins University

Selective-abortion-in-Montenegro-is-still-alive

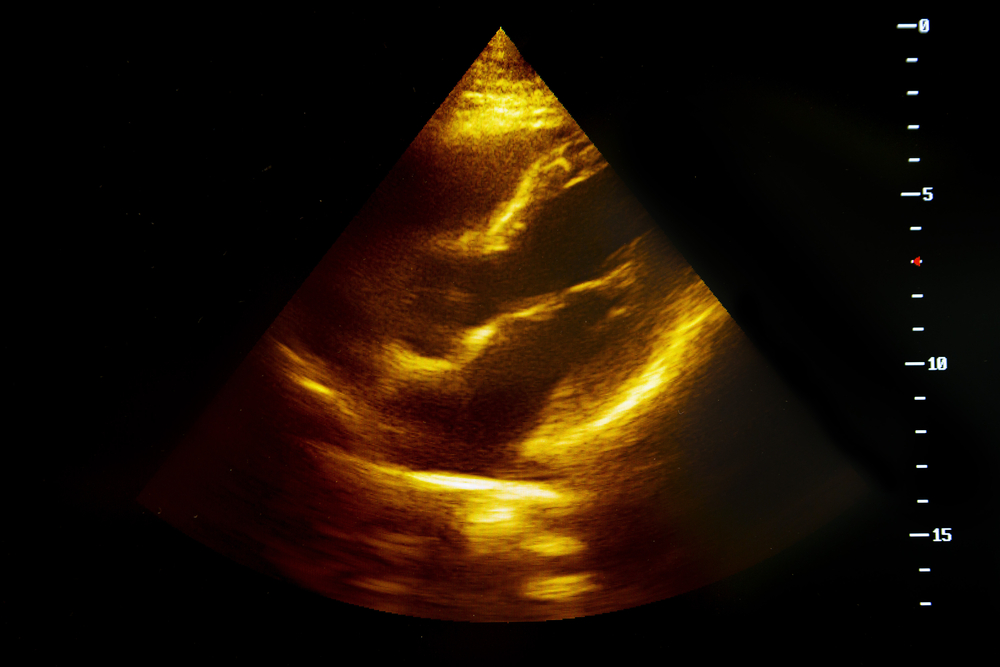

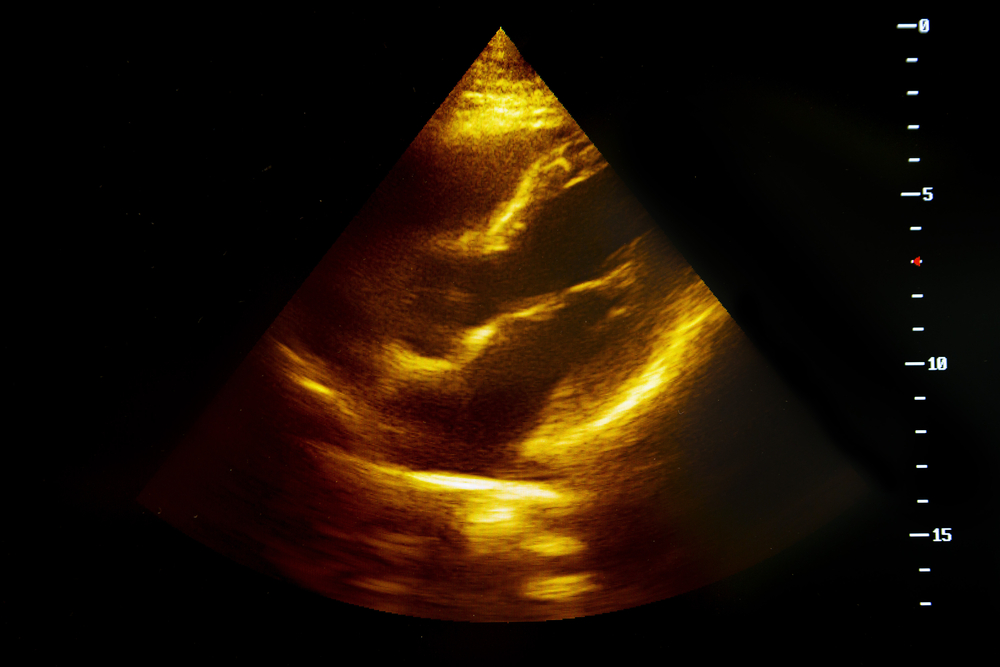

© Belish/Shutterstock

Could you briefly describe the practice of sex-selective abortion in Montenegro?

One of the main causes for choosing sex-selective abortion in Montenegro and also in other countries in the world is a traditional preference for sons. This practice is facilitated nowadays by access to modern technologies. What is interesting is that, if we consider the last 30-40 years, we can notice that the sex ratio at birth has started to raise in the mid-80s, I suppose because of the fact that it is very much connected to the spread of different kinds of medical technologies worldwide, including in Montenegro. It somehow started to stabilise in the 2000s and, if we look at the last two decades, the ratio has actually been declining: surely, gender roles are undergoing some changes and becoming more flexible, even if this practice has not completely disappeared.

How was the situation in Montenegro during the socialist period?

During state socialism, experiences in Montenegro were ambivalent. While the State promoted institutionalised equality by guaranteeing the right for both sexes to work, social protection, education and healthcare services, there were discrepancies in the position of women in the public and in the private sphere, among rural and urban areas, and different groups in the society. Women were encouraged to take an active part in decision-making processes, political life, and the State promised that this would lead to more gender equality. Abortion was legalised in 1952 and the 1974 Constitution established 12 months of maternity leave on full pay for all women. However, women experienced a double burden and actually they were not liberated from domestic work and had limited opportunities to become active in political life. Despite the progressive measures of the socialist period, patriarchal dynamics in heterosexual relationships persisted as well as unbalanced attitudes towards male and female children. As part of building a new society there was an attempt to change this patriarchal mindset, but this was not eradicated: female children were perceived as a tragedy and mothers were actually blamed for giving birth to them instead of a son, who was seen as a triumph for men.

How does patriarchy affect Montenegro nowadays?

I would like to answer by giving an example from my article , where I am talking about Ivana and her mother. Ivana is a young woman in her mid-twenties living in Podgorica, totally against son preference and sex-selective abortion, while her mother is a woman in her fifties, who also lives in Podgorica, who has two daughters and one son. The woman had several abortions in Serbia after having two daughters in order to have a son. Ivana is somehow positioning herself as a modern and progressive woman: this shows a dynamic of change among generations, but she is constantly feeling the pressure coming from society and her family. The idea of a son as a more desirable offspring is a part of her life through models embedded in the society, questions about her personal life during family gatherings, and the disappointment she felt from her husband when he discovered that he would have a daughter as a first child. This shows how patriarchal ideas are still alive and are affecting Montenegrin society, even though to a lesser extent.

How is son preference connected to gendered inheritance practices?

Historically, Montenegro’s traditional and kinship systems were male-centred and that means that men had the central power and resources in society. The family name and assets were inherited by male lineage, which means that only men could inherit. Sons were expected to live close to the father, to take care of aging parents; on the other hand, being a woman in Montenegro meant getting married, moving away from the family of origin, and taking care of the husband’s household and parents, serving a new family. A woman’s primary function was reproductive, so she had to give birth to children and she had no rights to inherit neither from the family of origin nor from the husband’s. We can observe that historically there has been a very strong preference to have a son in order to give him the family properties and resources: also, nowadays, giving property to a woman would significantly affect the balance of the patriarchal model because women would obtain some value outside their reproductive function. Passing property to a daughter would not only make her wealthier, but also her husband and his family, so actually it would mean giving away resources to an unknown family and taking them away from one’s own. Today the situation is not clear cut: for instance, in the north of Montenegro it is quite an usual practice that parents ask for a legal procedure to secure that in the future all the family’s assets will go to the son, making an official agreement with a lawyer, excluding daughters still, while there are young girls in Podgorica who own their own apartment, because they bought it.

What is the role of NGOs in Montenegro’s civil society?

NGOs play an important role in raising awareness on sex-selective abortion in Montenegro. I observed that at the local level in 2017, when a social campaign titled “Unwanted” was initiated by the Women’s Rights Center . This campaign also launched a petition to prevent prenatal testing, performed mainly in Serbia, to be abused to detect the sex of the baby, and to raise awareness about gender discrimination in Montenegro. Journalists were accepting this topic at that time and, for this reason, it had a very big media coverage, but it was not enough, because locally and internationally there is still a lack of sources on this topic. Personally, I would be a bit critical about the title of this campaign which say that daughters are unwanted in Montenegro, because I noticed that in the country the situation is slowly changing and in many cases families are more concerned about their financial situation, about the resources they have to secure a good childhood for their babies, rather than their sex.

Do you believe that this problem affecting the country is perceived and well-known around the world?

If we consider some countries such as India and China, the preference for sons and the sex imbalance is very visible and there have been many studies, books, documentaries, and discussions. Not the same knowledge is generally applicable to south-eastern European countries, including Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Montenegro, and some Caucasian countries, such as Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia. In the last ten years, both international and local actors have paid attention to Montenegro, and thanks to journalists who made various articles and interviews and the NGOs’ intervention, this problem has been acknowledged, but there is still a lack of academic resources. It is hard to ensure an answer to this question and, surely, in some parts of society this problem is well-known and recognised, while it is not acknowledged in many others. For example, when I started talking about this topic in Latvia, people were surprised, they did not know that these kinds of ideas and practices are carried out here in Europe. They knew about China and India, but nothing about Montenegro, that region, and the ideas that are still alive there.

Diana Dubrovska took part in a Horizon 2020 project called “Inform: closing the gap between formal and informal institutions in the Balkans” and at the same time she started investigating about son preference and sex-selective abortion in Montenegro. She also has done fieldwork in Montenegro starting from 2017, especially interviews. Her ethnographic research can be found here.

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Selective abortion: in Montenegro is still alive

Sex-selective abortion and son preference are still alive in Montenegro. We talked about that with Diana Dubrovska, a young Latvian anthropologist interested in sex, gender, and sexuality issues who is teaching at Riga Stradins University

Selective-abortion-in-Montenegro-is-still-alive

© Belish/Shutterstock

Could you briefly describe the practice of sex-selective abortion in Montenegro?

One of the main causes for choosing sex-selective abortion in Montenegro and also in other countries in the world is a traditional preference for sons. This practice is facilitated nowadays by access to modern technologies. What is interesting is that, if we consider the last 30-40 years, we can notice that the sex ratio at birth has started to raise in the mid-80s, I suppose because of the fact that it is very much connected to the spread of different kinds of medical technologies worldwide, including in Montenegro. It somehow started to stabilise in the 2000s and, if we look at the last two decades, the ratio has actually been declining: surely, gender roles are undergoing some changes and becoming more flexible, even if this practice has not completely disappeared.

How was the situation in Montenegro during the socialist period?

During state socialism, experiences in Montenegro were ambivalent. While the State promoted institutionalised equality by guaranteeing the right for both sexes to work, social protection, education and healthcare services, there were discrepancies in the position of women in the public and in the private sphere, among rural and urban areas, and different groups in the society. Women were encouraged to take an active part in decision-making processes, political life, and the State promised that this would lead to more gender equality. Abortion was legalised in 1952 and the 1974 Constitution established 12 months of maternity leave on full pay for all women. However, women experienced a double burden and actually they were not liberated from domestic work and had limited opportunities to become active in political life. Despite the progressive measures of the socialist period, patriarchal dynamics in heterosexual relationships persisted as well as unbalanced attitudes towards male and female children. As part of building a new society there was an attempt to change this patriarchal mindset, but this was not eradicated: female children were perceived as a tragedy and mothers were actually blamed for giving birth to them instead of a son, who was seen as a triumph for men.

How does patriarchy affect Montenegro nowadays?

I would like to answer by giving an example from my article , where I am talking about Ivana and her mother. Ivana is a young woman in her mid-twenties living in Podgorica, totally against son preference and sex-selective abortion, while her mother is a woman in her fifties, who also lives in Podgorica, who has two daughters and one son. The woman had several abortions in Serbia after having two daughters in order to have a son. Ivana is somehow positioning herself as a modern and progressive woman: this shows a dynamic of change among generations, but she is constantly feeling the pressure coming from society and her family. The idea of a son as a more desirable offspring is a part of her life through models embedded in the society, questions about her personal life during family gatherings, and the disappointment she felt from her husband when he discovered that he would have a daughter as a first child. This shows how patriarchal ideas are still alive and are affecting Montenegrin society, even though to a lesser extent.

How is son preference connected to gendered inheritance practices?

Historically, Montenegro’s traditional and kinship systems were male-centred and that means that men had the central power and resources in society. The family name and assets were inherited by male lineage, which means that only men could inherit. Sons were expected to live close to the father, to take care of aging parents; on the other hand, being a woman in Montenegro meant getting married, moving away from the family of origin, and taking care of the husband’s household and parents, serving a new family. A woman’s primary function was reproductive, so she had to give birth to children and she had no rights to inherit neither from the family of origin nor from the husband’s. We can observe that historically there has been a very strong preference to have a son in order to give him the family properties and resources: also, nowadays, giving property to a woman would significantly affect the balance of the patriarchal model because women would obtain some value outside their reproductive function. Passing property to a daughter would not only make her wealthier, but also her husband and his family, so actually it would mean giving away resources to an unknown family and taking them away from one’s own. Today the situation is not clear cut: for instance, in the north of Montenegro it is quite an usual practice that parents ask for a legal procedure to secure that in the future all the family’s assets will go to the son, making an official agreement with a lawyer, excluding daughters still, while there are young girls in Podgorica who own their own apartment, because they bought it.

What is the role of NGOs in Montenegro’s civil society?

NGOs play an important role in raising awareness on sex-selective abortion in Montenegro. I observed that at the local level in 2017, when a social campaign titled “Unwanted” was initiated by the Women’s Rights Center . This campaign also launched a petition to prevent prenatal testing, performed mainly in Serbia, to be abused to detect the sex of the baby, and to raise awareness about gender discrimination in Montenegro. Journalists were accepting this topic at that time and, for this reason, it had a very big media coverage, but it was not enough, because locally and internationally there is still a lack of sources on this topic. Personally, I would be a bit critical about the title of this campaign which say that daughters are unwanted in Montenegro, because I noticed that in the country the situation is slowly changing and in many cases families are more concerned about their financial situation, about the resources they have to secure a good childhood for their babies, rather than their sex.

Do you believe that this problem affecting the country is perceived and well-known around the world?

If we consider some countries such as India and China, the preference for sons and the sex imbalance is very visible and there have been many studies, books, documentaries, and discussions. Not the same knowledge is generally applicable to south-eastern European countries, including Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Montenegro, and some Caucasian countries, such as Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia. In the last ten years, both international and local actors have paid attention to Montenegro, and thanks to journalists who made various articles and interviews and the NGOs’ intervention, this problem has been acknowledged, but there is still a lack of academic resources. It is hard to ensure an answer to this question and, surely, in some parts of society this problem is well-known and recognised, while it is not acknowledged in many others. For example, when I started talking about this topic in Latvia, people were surprised, they did not know that these kinds of ideas and practices are carried out here in Europe. They knew about China and India, but nothing about Montenegro, that region, and the ideas that are still alive there.

Diana Dubrovska took part in a Horizon 2020 project called “Inform: closing the gap between formal and informal institutions in the Balkans” and at the same time she started investigating about son preference and sex-selective abortion in Montenegro. She also has done fieldwork in Montenegro starting from 2017, especially interviews. Her ethnographic research can be found here.