Why the Romanian state is not attracting more EU funds, even though it needs the money

Since 2007, the year Romania entered the EU, over 62 billion euros have flowed into the country from the EU. There could have been more, but the Romanian state failed to attract them all. Why?

Romania-e-fondi-UE-un-paese-in-costante-ritardo

European commission, Bruxelles, Belgium © symbiot/Shutterstock

(Originally published by our project partner PressOne )

In January 2007, when Romania was celebrating its accession to the European Union, more than half of the population had no sewerage, the GDP/capita ratio was less than half the European average and the average net salary was 1,042 lei. So the country looked with confidence towards the European project (75% was the level of confidence Romanians had in the EU in 2007) and with hope towards the tens of billions of euros for roads, water, sewers, schools and hospitals. Romania dreamed of being a modern country.

After 16 years, Romania’s per capita GDP is close to that of Hungary and Poland, the average net salary has reached 4,593 lei, and more than €62 billion from the European Union has flowed into the country. There would have been more money, but the Romanian state has failed to attract it all. PressOne explains why.

Romania has benefited from EU funds since pre-accession

Cohesion policy is the EU’s main way of investing in its member countries. To what end? Reducing economic, social and territorial disparities within the European bloc, where Romania has received access to tens of billions of euros through cohesion policy since 2007.

“Almost 16 years after accession, Romania has contributed around €21 billion to the EU budget and, in parallel, received €62 billion. So a positive balance of at least 41 billion,” explains Ana-Maria Icătoiu, an expert on access to EU funds and vice-president of the UGIR Women Entrepreneurs’ Organisation (OFA).

EU money has been flowing into Romania since the pre-accession phase, giving a boost to certain sectors, such as agriculture.

“Before joining the EU, Romania had some heating programmes, the so-called PHARE programmes. On the back of that, for example, many processing plants were built. And this has paid off, because it made the transition to European funds,” economic analyst Constantin Rudnițchi tells PressOne.

But the experience with European money before accession does not seem to have helped Romania much, especially as bureaucratic and structural difficulties and, at times, the reluctance of political decision-makers to use European funds, which are much more strictly supervised, have made Romania a country that still struggles for money that others attract much more easily.

First contact with EU money. First priorities

The outlook is not good. If the EU expands, the cohesion funds Romania receives will be much less. “It’s pretty much the last train on the cohesion front,” says REPER MEP Dragoș Pâslaru.

After accession, Romania was able to access EU funds for the 2007-2013 financial year, totalling around €27 billion which could be attracted under 7 operational programmes.

The priorities at the time were investment in infrastructure and accessibility, i.e. new roads built with European money. Next on the list were research and innovation, SMEs, education and training, social inclusion and the environment.

“At the end of the first programming period, 2007-2013, due to the fact that we were in a very bad situation in terms of real absorption at the end of the period, i.e. somewhere around 2014-2015, because each time the period is extended by a year or two, some artifices were made: some investment works, many made by local authorities, which were compatible with the regional programme at that time, were settled from European funds. From paving, parks, roads, basic local investment works”, says Ana-Maria Icătoiu, an expert in accessing European funds.

Despite the fact that the money allocated to Romania in the 2007-2013 period was not fully attracted, cohesion funds accounted for 35% of total public investments made by the authorities in the period mentioned above, said former Prime Minister Nicolae Ciucă in April 2023.

7 years’ job, accomplished in 10

Seven years later, a new financial cycle, 2014-2020, was negotiated and voted at EU level to deliver the Europe 2020 objectives. No less than 11 investment areas were envisaged for the 2014-2022 period, including research, development and innovation, digitisation, more competitive SMEs, the transition to a green economy, risk management and climate change, environmental conservation and protection, sustainable transport and investment in education and training to combat all forms of discrimination.

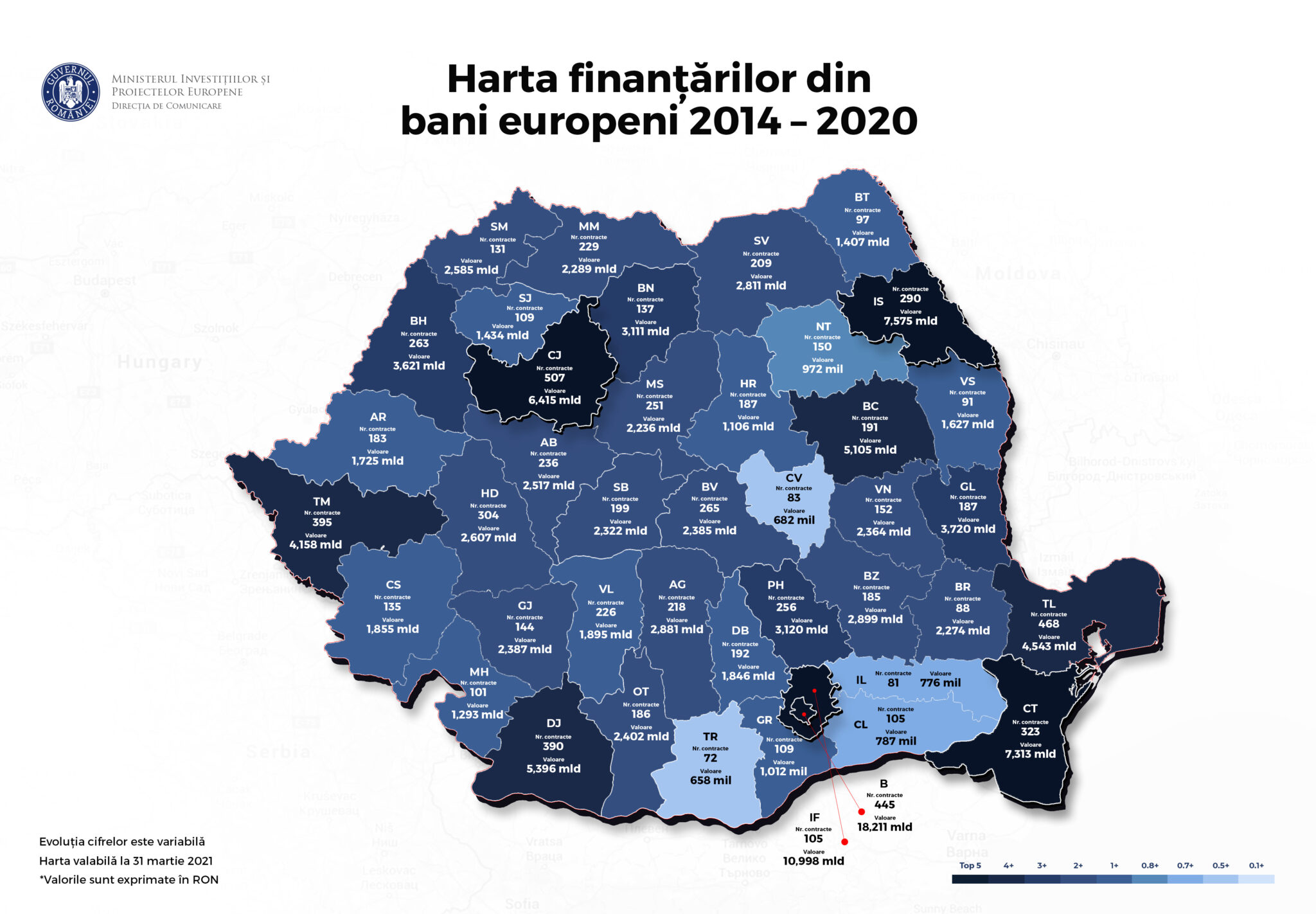

Romania has been allocated €41 billion from the European structural and investment funds, of which more than €35 billion from the European budget alone through cohesion policy.

The money could be attracted through 8 operational programmes managed by three managing authorities: the Ministry of European Investment and Projects, the Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development.

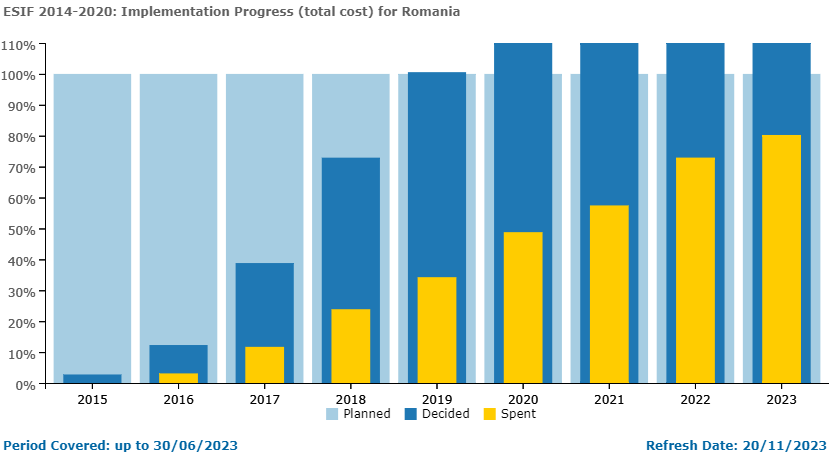

According to the latest data, the absorption rate of funds for the 2014-2020 period is just over 84%. Romania still has until the end of the year to complete all projects.

“In order for this to happen, theoretically you should have submitted invoices by the end of the year (…) There is something else that can happen, namely deducting certain types of expenditure you have made and reclassifying them as expenditure on European money”, explains REPER MEP Dragoș Pâslaru.

For example, says the MEP, Romania obtained from the European Commission that a good part of the compensation for energy bills be settled from the European money it had available. And now they are trying to shift as much expenditure as possible to European money in order to artificially increase the absorption rate of the funds.

In his opinion, the word that best describes Romania in its relationship with European money is “delay”.

“Every time we start about 2, 3 years late in the budget year. That’s how long it takes us to accredit the institutions, to prepare the administration, the projects, the tenders. Let’s say that in 2007 it took us a while to get used to European rigours and standards. But since 2013 we should have had no more excuses. And because projects come late, they end up being prolonged,” Constantin Rudnițchi tells PressOne.

Overlapping financial programming

This is why there are currently two overlapping financial cycles: 2014-2020 and 2021-2027. The former was extended by three years to allow as many projects as possible to be completed, while the latter has barely started, although two years have already passed. The reason for the delay? It was only in July 2022 that the framework partnership agreement was signed with the European Commission, which is the basis for the distribution of cohesion policy money. It was only afterwards that the other structures involved in managing EU funds were accredited.

For the next few years, Romania will have a budget of €46 billion, of which almost €31 billion will come from the European budget. The money will be available through 16 operational programmes, 8 national and 8 regional.

For the first time, regional development investment budgets have been given to the 8 regional development agencies (RDAs) and will no longer be administered by a central authority.

“I think the advantage of decentralisation is, on the one hand, that the RDAs have experience and move faster than a ministry-level authority. And they are closer to the region. They can better see what needs to be developed in the region,” says Constantin Rudnițchi.

While in 2007 digitisation and green transition were not high on the list of investment priorities, they are now important pillars of all European funding lines.

“We are talking about sectors such as green energy, carbon reduction, environmental infrastructure, biodiversity conservation, green space creation, risk management and sustainable urban mobility measures,” says USR MEP Vlad Gheorghe.

Why we are the last when it comes to attracting EU funds, even though we depend on them the most

While the private sector is doing very well at absorbing all the funds dedicated to it, with applications for funding exceeding 1,200% of the allocated budget, public authorities are not doing so well.

“On the one hand, the big infrastructure projects, from railways to motorways, water, sewage and energy extension projects, for reasons we keep hearing about on TV, are not getting implemented. This also includes regional hospitals, which we have been pulling on for 12-13 years”, says Ana-Maria Icătoiu, expert in accessing European funds and vice-president of OFA UGIR.

Another explanation for the low absorption rate of EU funds is hidden in the projects financed from the national budget.

“Although, in theory, Romania would not be allowed to launch national programmes, i.e. with funds from the national budget, that cannibalise funds from the European Union, i.e. finance the same thing, we have always done it. When you, as mayor or president of a local government, see that you have some European funds where the level of verification, especially in procurement procedures, is very high, would you apply for European funds or would you go for a PNDL, Anghel Saligny?”, continues the expert in European funds.

For example, if not all projects from the 2014-2020 financial year are completed by the end of this year, there are two possibilities: either the money received is returned to the European Commission and the projects are closed, or the projects are continued, but with money from the national budget. As was the case with the hospitals removed from the list of PNRR funding, for which the government promised to borrow from the European Investment Bank.

The details that shrink the budget for 2021-2027

To avoid this, there are certain procedures that public authorities can resort to. Among them is the so-called phasing-in procedure, whereby unfinished projects are not cancelled but simply moved from one financial year to another.

“The cut-off procedure is a classic procedure that Romania, because it never gets things done on time, has already used twice. But this time it is more complicated, because only projects that comply with the conditions of the 2021-2027 regulation can be phased in. That means only those projects that do not have a harmful impact on the environment. This means that instead of attracting new projects in the next few years, you will devote part of it to completing old projects”, explains REPER MEP Dragoș Pâslaru.

With two overlapping financial years, several years’ delays in starting projects and the public authorities’ affection for national funds, we asked experts what the chances are of Romania attracting more money in the future. Especially when the money from the NRDP is also in the picture, and the state needs to start real reforms to attract it.

Reforms needed

In 2007, the European Commission did not trust national control mechanisms when it came to European money, such as the Court of Auditors. So a new layer of institutions was created to ensure that EU money was spent within the law, institutions that don’t exist in many other European countries.

“In Romania there is a different treatment of European money from national money. I mean European money has its own ministry, its own control procedures. We have a different treatment, with salary bonuses of 75% and all sorts of very nice procedures. With national money you have neither salary bonuses, nor evaluation and monitoring procedures, and this is an extremely serious matter, and this is the first big reform that should be made in Romania with European money: to put all the funds in one bucket”, explains Pâslaru.

The logic that we should arrive at, says Dragoș Pâslaru, is that public policies should no longer depend on European funds.

“The major problem is that we don’t have policies that change from one moment to the next, or policies that are not necessarily affected by financial cycles, we practically start from scratch every time. So we make policies for European money”, is the conclusion drawn by the MEP.

This content is published in the context of the “Energy4Future” project co-financed by the European Union (EU). The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project. The responsibility for the contents lies solely with OBC Transeuropa.

Tag: Energy for Future

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Why the Romanian state is not attracting more EU funds, even though it needs the money

Since 2007, the year Romania entered the EU, over 62 billion euros have flowed into the country from the EU. There could have been more, but the Romanian state failed to attract them all. Why?

Romania-e-fondi-UE-un-paese-in-costante-ritardo

European commission, Bruxelles, Belgium © symbiot/Shutterstock

(Originally published by our project partner PressOne )

In January 2007, when Romania was celebrating its accession to the European Union, more than half of the population had no sewerage, the GDP/capita ratio was less than half the European average and the average net salary was 1,042 lei. So the country looked with confidence towards the European project (75% was the level of confidence Romanians had in the EU in 2007) and with hope towards the tens of billions of euros for roads, water, sewers, schools and hospitals. Romania dreamed of being a modern country.

After 16 years, Romania’s per capita GDP is close to that of Hungary and Poland, the average net salary has reached 4,593 lei, and more than €62 billion from the European Union has flowed into the country. There would have been more money, but the Romanian state has failed to attract it all. PressOne explains why.

Romania has benefited from EU funds since pre-accession

Cohesion policy is the EU’s main way of investing in its member countries. To what end? Reducing economic, social and territorial disparities within the European bloc, where Romania has received access to tens of billions of euros through cohesion policy since 2007.

“Almost 16 years after accession, Romania has contributed around €21 billion to the EU budget and, in parallel, received €62 billion. So a positive balance of at least 41 billion,” explains Ana-Maria Icătoiu, an expert on access to EU funds and vice-president of the UGIR Women Entrepreneurs’ Organisation (OFA).

EU money has been flowing into Romania since the pre-accession phase, giving a boost to certain sectors, such as agriculture.

“Before joining the EU, Romania had some heating programmes, the so-called PHARE programmes. On the back of that, for example, many processing plants were built. And this has paid off, because it made the transition to European funds,” economic analyst Constantin Rudnițchi tells PressOne.

But the experience with European money before accession does not seem to have helped Romania much, especially as bureaucratic and structural difficulties and, at times, the reluctance of political decision-makers to use European funds, which are much more strictly supervised, have made Romania a country that still struggles for money that others attract much more easily.

First contact with EU money. First priorities

The outlook is not good. If the EU expands, the cohesion funds Romania receives will be much less. “It’s pretty much the last train on the cohesion front,” says REPER MEP Dragoș Pâslaru.

After accession, Romania was able to access EU funds for the 2007-2013 financial year, totalling around €27 billion which could be attracted under 7 operational programmes.

The priorities at the time were investment in infrastructure and accessibility, i.e. new roads built with European money. Next on the list were research and innovation, SMEs, education and training, social inclusion and the environment.

“At the end of the first programming period, 2007-2013, due to the fact that we were in a very bad situation in terms of real absorption at the end of the period, i.e. somewhere around 2014-2015, because each time the period is extended by a year or two, some artifices were made: some investment works, many made by local authorities, which were compatible with the regional programme at that time, were settled from European funds. From paving, parks, roads, basic local investment works”, says Ana-Maria Icătoiu, an expert in accessing European funds.

Despite the fact that the money allocated to Romania in the 2007-2013 period was not fully attracted, cohesion funds accounted for 35% of total public investments made by the authorities in the period mentioned above, said former Prime Minister Nicolae Ciucă in April 2023.

7 years’ job, accomplished in 10

Seven years later, a new financial cycle, 2014-2020, was negotiated and voted at EU level to deliver the Europe 2020 objectives. No less than 11 investment areas were envisaged for the 2014-2022 period, including research, development and innovation, digitisation, more competitive SMEs, the transition to a green economy, risk management and climate change, environmental conservation and protection, sustainable transport and investment in education and training to combat all forms of discrimination.

Romania has been allocated €41 billion from the European structural and investment funds, of which more than €35 billion from the European budget alone through cohesion policy.

The money could be attracted through 8 operational programmes managed by three managing authorities: the Ministry of European Investment and Projects, the Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development.

According to the latest data, the absorption rate of funds for the 2014-2020 period is just over 84%. Romania still has until the end of the year to complete all projects.

“In order for this to happen, theoretically you should have submitted invoices by the end of the year (…) There is something else that can happen, namely deducting certain types of expenditure you have made and reclassifying them as expenditure on European money”, explains REPER MEP Dragoș Pâslaru.

For example, says the MEP, Romania obtained from the European Commission that a good part of the compensation for energy bills be settled from the European money it had available. And now they are trying to shift as much expenditure as possible to European money in order to artificially increase the absorption rate of the funds.

In his opinion, the word that best describes Romania in its relationship with European money is “delay”.

“Every time we start about 2, 3 years late in the budget year. That’s how long it takes us to accredit the institutions, to prepare the administration, the projects, the tenders. Let’s say that in 2007 it took us a while to get used to European rigours and standards. But since 2013 we should have had no more excuses. And because projects come late, they end up being prolonged,” Constantin Rudnițchi tells PressOne.

Overlapping financial programming

This is why there are currently two overlapping financial cycles: 2014-2020 and 2021-2027. The former was extended by three years to allow as many projects as possible to be completed, while the latter has barely started, although two years have already passed. The reason for the delay? It was only in July 2022 that the framework partnership agreement was signed with the European Commission, which is the basis for the distribution of cohesion policy money. It was only afterwards that the other structures involved in managing EU funds were accredited.

For the next few years, Romania will have a budget of €46 billion, of which almost €31 billion will come from the European budget. The money will be available through 16 operational programmes, 8 national and 8 regional.

For the first time, regional development investment budgets have been given to the 8 regional development agencies (RDAs) and will no longer be administered by a central authority.

“I think the advantage of decentralisation is, on the one hand, that the RDAs have experience and move faster than a ministry-level authority. And they are closer to the region. They can better see what needs to be developed in the region,” says Constantin Rudnițchi.

While in 2007 digitisation and green transition were not high on the list of investment priorities, they are now important pillars of all European funding lines.

“We are talking about sectors such as green energy, carbon reduction, environmental infrastructure, biodiversity conservation, green space creation, risk management and sustainable urban mobility measures,” says USR MEP Vlad Gheorghe.

Why we are the last when it comes to attracting EU funds, even though we depend on them the most

While the private sector is doing very well at absorbing all the funds dedicated to it, with applications for funding exceeding 1,200% of the allocated budget, public authorities are not doing so well.

“On the one hand, the big infrastructure projects, from railways to motorways, water, sewage and energy extension projects, for reasons we keep hearing about on TV, are not getting implemented. This also includes regional hospitals, which we have been pulling on for 12-13 years”, says Ana-Maria Icătoiu, expert in accessing European funds and vice-president of OFA UGIR.

Another explanation for the low absorption rate of EU funds is hidden in the projects financed from the national budget.

“Although, in theory, Romania would not be allowed to launch national programmes, i.e. with funds from the national budget, that cannibalise funds from the European Union, i.e. finance the same thing, we have always done it. When you, as mayor or president of a local government, see that you have some European funds where the level of verification, especially in procurement procedures, is very high, would you apply for European funds or would you go for a PNDL, Anghel Saligny?”, continues the expert in European funds.

For example, if not all projects from the 2014-2020 financial year are completed by the end of this year, there are two possibilities: either the money received is returned to the European Commission and the projects are closed, or the projects are continued, but with money from the national budget. As was the case with the hospitals removed from the list of PNRR funding, for which the government promised to borrow from the European Investment Bank.

The details that shrink the budget for 2021-2027

To avoid this, there are certain procedures that public authorities can resort to. Among them is the so-called phasing-in procedure, whereby unfinished projects are not cancelled but simply moved from one financial year to another.

“The cut-off procedure is a classic procedure that Romania, because it never gets things done on time, has already used twice. But this time it is more complicated, because only projects that comply with the conditions of the 2021-2027 regulation can be phased in. That means only those projects that do not have a harmful impact on the environment. This means that instead of attracting new projects in the next few years, you will devote part of it to completing old projects”, explains REPER MEP Dragoș Pâslaru.

With two overlapping financial years, several years’ delays in starting projects and the public authorities’ affection for national funds, we asked experts what the chances are of Romania attracting more money in the future. Especially when the money from the NRDP is also in the picture, and the state needs to start real reforms to attract it.

Reforms needed

In 2007, the European Commission did not trust national control mechanisms when it came to European money, such as the Court of Auditors. So a new layer of institutions was created to ensure that EU money was spent within the law, institutions that don’t exist in many other European countries.

“In Romania there is a different treatment of European money from national money. I mean European money has its own ministry, its own control procedures. We have a different treatment, with salary bonuses of 75% and all sorts of very nice procedures. With national money you have neither salary bonuses, nor evaluation and monitoring procedures, and this is an extremely serious matter, and this is the first big reform that should be made in Romania with European money: to put all the funds in one bucket”, explains Pâslaru.

The logic that we should arrive at, says Dragoș Pâslaru, is that public policies should no longer depend on European funds.

“The major problem is that we don’t have policies that change from one moment to the next, or policies that are not necessarily affected by financial cycles, we practically start from scratch every time. So we make policies for European money”, is the conclusion drawn by the MEP.

This content is published in the context of the “Energy4Future” project co-financed by the European Union (EU). The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project. The responsibility for the contents lies solely with OBC Transeuropa.

Tag: Energy for Future