Novi Pazar, the bazaar without lipstick

It is very similar to the Ottoman-style quarter in Sarajevo, though many consider it more genuine, the čaršija from which Novi Pazar in south-eastern Serbia gets its name. Our feature

Novi Pazar can be found at the end of a road which winds through hills and mountains of southern Serbia for kilometer after kilometer. One’s first impression of Novi Pazar is its social-realist history, mingled with the hurried architecture of recent years. And there among the socialist buildings, some of which are quite harmonious and original, is a cluster of prefabricated buildings with shops on the ground floor selling Turkish and Chinese merchandise.

Then one reaches the heart of town, made up of nothing less than a market – built to replace the old town, the historical Ras, where the first medieval Serbian state was founded by the Nemanjic dynasty.

Many of the monuments in Novi Pazar recall that period, although the heart of town is in typically Ottoman architectural style.

As the name itself suggests, Novi Pazar began in fact as a market, on the outskirts of the medieval Serbian town, resembling a typical Ottoman čaršija*, preserved in its original form to the present day.

The Baščaršija without lipstick

Its inhabitants now call it “the Baščaršija without lipstick”: a well-preserved čaršija, in many ways similar to the Baščaršija in Sarajevo, but more modest and less extravagant.

Although it has now become the destination for a certain kind of alternative tourism, the Novi Pazar čaršija continues – in a very natural manner – to maintain its traditional function as a market and meeting place for its local people.

Built between 1459 and 1461 by Isa Beg Isaković, who also founded the Baščaršija in Sarajevo, the bazaar, at the foot of the Raška fortress, took the name “Novi Pazar”, meaning “new market”. A place reserved for the merchants of the caravanserai to meet and exchange their goods, and a crossroads between important towns of the Ottoman era.

This “new market” is in fact located at the junction between longitudinal communication routes that connect the ancient Ragusa, Sarajevo, Istanbul, Niš and Sofia, and the north-south line which linked Budapest, Belgrade and the southern part of the Ottoman Balkans.

Cohabitation

Despite the strong dynamics of “provincialisation” of the area, following the conflicts in former Jugoslavia, the town’s multiethnic character differentiates it from the standard Serbian demographic structure. About 70% of its population is in fact constituted by Bosniaks, of Muslim faith, but there are also Serbs, Albanians, Gorani, Roma, and Montenegrins. Its peculiar nature places Novi Pazar at the center of lively debates about the rights of religious and linguistic minorities in Serbia.

The impression however, walking through the town, is quite another. Veiled women stroll beside those in miniskirts, languages mingle and even Serbian here acquires Albanian-Kosovar and northern Macedonian nuances.

In a kafana, some men are celebrating, drinking and singing. They allow us to take their photograph without objection and, introducing themselves, speak all the languages they know. Among them is a Kosovar returned from a long emigration to Switzerland, some local Bosniaks and a Serbian, in a festive atmosphere, mixed with alcohol and the rhythm of Jugoslav songs from the 70s.

Among those fearing potential conflicts in the Balkans, Novi Pazar is one of the most high risk and frequently cited places. Being a border town, and the majority of its citizens having Muslim faith, are given as the main reasons for this, but according to the townspeople such conflicts are remote.

This can also be felt in the life of the čaršija: a calm pace of life in which socializing in the cafés, or even on the pavement, seems to take precedence over the commercial activities of the čaršija and defies any divisive structure based on religion or nationality.

“Here everyone is free to be what they are,” explains a young Goran, “religion is something personal.” A Serbian who wishes to be interviewed is of the same opinion: “I work with Bosniaks and Albanians. We get on really well, they are honest. And, above all, we are people – all equal – and, only after that, are we Orthodox or Muslim.”

The future of the čaršija

Even if the čaršija of Novi Pazar has not lost its central role in the town, the buildings in abysmal condition are numerous, and the čaršija quarter shows the signs of age and of the difficult transition of the last twenty years.

The need for restoration, promotion and improvement is evident and urgent, and some have already taken steps in this direction, not limiting themselves strictly to the čaršija.

“We have decided not to concentrate solely on the material and visible, but to develop a line which appreciates the cultural heritage of the area, including ‘minor’ aspects of the whole valley of the River Ibar – the food, traditional costume, music and literature – therefore appreciating the land through a multidisciplinary and flexible approach, dedicating equal attention to both the material and the less tangible” explains Lazar Nisavić of the association Sodalis.

The association headed by Lazar collaborates with the programme SeeNet II in a cross-border project which includes Novi Pazar and its čaršija. Local institutions, cultural institutions and religious communities have been involved in defining a tourist macro-system according to the concept of “Ecomuseum”. Originating in France in the 80s, the intention of the Ecomuseum is to help the visitor to explore the surrounding terrain, thus overcoming the limits of the expository museum, where the visitor receives information passively and not as a protagonist in the exploration.

We hope that this kind of exploration may more and more frequently begin from the “new market” of Novi Pazar, the Baščaršija without lipstick.

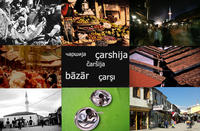

* To make reading easier the ‘bchs’ version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

Tag: Seenet

Novi Pazar, the bazaar without lipstick

It is very similar to the Ottoman-style quarter in Sarajevo, though many consider it more genuine, the čaršija from which Novi Pazar in south-eastern Serbia gets its name. Our feature

Novi Pazar can be found at the end of a road which winds through hills and mountains of southern Serbia for kilometer after kilometer. One’s first impression of Novi Pazar is its social-realist history, mingled with the hurried architecture of recent years. And there among the socialist buildings, some of which are quite harmonious and original, is a cluster of prefabricated buildings with shops on the ground floor selling Turkish and Chinese merchandise.

Then one reaches the heart of town, made up of nothing less than a market – built to replace the old town, the historical Ras, where the first medieval Serbian state was founded by the Nemanjic dynasty.

Many of the monuments in Novi Pazar recall that period, although the heart of town is in typically Ottoman architectural style.

As the name itself suggests, Novi Pazar began in fact as a market, on the outskirts of the medieval Serbian town, resembling a typical Ottoman čaršija*, preserved in its original form to the present day.

The Baščaršija without lipstick

Its inhabitants now call it “the Baščaršija without lipstick”: a well-preserved čaršija, in many ways similar to the Baščaršija in Sarajevo, but more modest and less extravagant.

Although it has now become the destination for a certain kind of alternative tourism, the Novi Pazar čaršija continues – in a very natural manner – to maintain its traditional function as a market and meeting place for its local people.

Built between 1459 and 1461 by Isa Beg Isaković, who also founded the Baščaršija in Sarajevo, the bazaar, at the foot of the Raška fortress, took the name “Novi Pazar”, meaning “new market”. A place reserved for the merchants of the caravanserai to meet and exchange their goods, and a crossroads between important towns of the Ottoman era.

This “new market” is in fact located at the junction between longitudinal communication routes that connect the ancient Ragusa, Sarajevo, Istanbul, Niš and Sofia, and the north-south line which linked Budapest, Belgrade and the southern part of the Ottoman Balkans.

Cohabitation

Despite the strong dynamics of “provincialisation” of the area, following the conflicts in former Jugoslavia, the town’s multiethnic character differentiates it from the standard Serbian demographic structure. About 70% of its population is in fact constituted by Bosniaks, of Muslim faith, but there are also Serbs, Albanians, Gorani, Roma, and Montenegrins. Its peculiar nature places Novi Pazar at the center of lively debates about the rights of religious and linguistic minorities in Serbia.

The impression however, walking through the town, is quite another. Veiled women stroll beside those in miniskirts, languages mingle and even Serbian here acquires Albanian-Kosovar and northern Macedonian nuances.

In a kafana, some men are celebrating, drinking and singing. They allow us to take their photograph without objection and, introducing themselves, speak all the languages they know. Among them is a Kosovar returned from a long emigration to Switzerland, some local Bosniaks and a Serbian, in a festive atmosphere, mixed with alcohol and the rhythm of Jugoslav songs from the 70s.

Among those fearing potential conflicts in the Balkans, Novi Pazar is one of the most high risk and frequently cited places. Being a border town, and the majority of its citizens having Muslim faith, are given as the main reasons for this, but according to the townspeople such conflicts are remote.

This can also be felt in the life of the čaršija: a calm pace of life in which socializing in the cafés, or even on the pavement, seems to take precedence over the commercial activities of the čaršija and defies any divisive structure based on religion or nationality.

“Here everyone is free to be what they are,” explains a young Goran, “religion is something personal.” A Serbian who wishes to be interviewed is of the same opinion: “I work with Bosniaks and Albanians. We get on really well, they are honest. And, above all, we are people – all equal – and, only after that, are we Orthodox or Muslim.”

The future of the čaršija

Even if the čaršija of Novi Pazar has not lost its central role in the town, the buildings in abysmal condition are numerous, and the čaršija quarter shows the signs of age and of the difficult transition of the last twenty years.

The need for restoration, promotion and improvement is evident and urgent, and some have already taken steps in this direction, not limiting themselves strictly to the čaršija.

“We have decided not to concentrate solely on the material and visible, but to develop a line which appreciates the cultural heritage of the area, including ‘minor’ aspects of the whole valley of the River Ibar – the food, traditional costume, music and literature – therefore appreciating the land through a multidisciplinary and flexible approach, dedicating equal attention to both the material and the less tangible” explains Lazar Nisavić of the association Sodalis.

The association headed by Lazar collaborates with the programme SeeNet II in a cross-border project which includes Novi Pazar and its čaršija. Local institutions, cultural institutions and religious communities have been involved in defining a tourist macro-system according to the concept of “Ecomuseum”. Originating in France in the 80s, the intention of the Ecomuseum is to help the visitor to explore the surrounding terrain, thus overcoming the limits of the expository museum, where the visitor receives information passively and not as a protagonist in the exploration.

We hope that this kind of exploration may more and more frequently begin from the “new market” of Novi Pazar, the Baščaršija without lipstick.

* To make reading easier the ‘bchs’ version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

Tag: Seenet