Sea of Azov: Mariupol’s iron dust

Despite the proximity to the Donbass conflict, there is an air of normalcy in Mariupol, Ukraine. But that very air is heavily polluted by the historic Metinvest metallurgical complex

Mare-d-Azov-la-polvere-di-ferro-di-Mariupol

The industrial area of Mariupol – photo by Claudia Bettiol

Capital of metallurgy and a major port on the Azov Sea with almost half a million inhabitants (the population has been decreasing slightly since 2014), Mariupol is one of the ten largest cities in Ukraine as well as the country’s most important industrial and economic centre. In 2019, the city has conquered the seventh place in the ranking of the most liveable places in Ukraine, despite being a few kilometres from the war front with Russia and the catastrophic ecological situation. The air in Mariupol is, in fact, the dirtiest in the country, there is a pungent smell of formaldehyde and zinc, and you can breathe iron dust.

Background

Since the ninth century, the lands on the Azov Sea hosted trade routes between the countries of the Caucasus and the Slavic lands of Kievan Rus’, which had colonised the steppes of present-day eastern Ukraine (the "dyke pole", wild field, described in the novel Voroshylovhrad by writer Serhiy Zadan). It was along these coasts that Prince Svyatoslav Igorevic, called the Brave, founded the first centre of the region, Bilhorod. Located near Mariupol, the Crimean Tatars later renamed it Bilosaraj (white palace); for this reason the beach near Mariupol still bears the name of Bilosarajska Kosa.

The city centre of what is now Mariupol took shape in the 9th-10th centuries, but only developed in the 16th century thanks to the Zaporizzja Cossacks who aimed to protect trade and roads from invasions from the south. The city was officially founded in 1778, and was named Mariupol by Empress Catherine II in March 1780 in honour of Marija Fedorovna, wife of the future emperor Paul I. In the surroundings, the villages of Bachcysaraj, Yalta, Urzuf, Sartana, and many others were built: all settlements founded by the Greeks who came from the homonymous areas of the Crimean peninsula.

After more than a hundred years under the Russian Empire, on December 30th, 1917 the Soviet power took office in Mariupol and in 1920 the famous metallurgical plants born in the late 19th century "A" ("Nikopol Mariupol") and "B" ("Russian Providence ") were nationalised and merged into a single complex which was named Illic in honor of Vladimir Lenin, in 1924. Together with the metallurgical giant Azovstal’, founded in the 1930s, Illic is today the largest factory not only in the Azov region and in the Donetsk, but also the main metallurgical plant of the former Soviet and present Ukraine. It supplies raw materials (mainly agglomerates) and fully processes and transforms metals (iron, zinc, steel), exporting its products in over 50 countries.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the industrial base of Mariupol adapted to meet the country’s military needs; many workers enlisted, mostly taking part in the winter war between the USSR and Finland (November 30th, 1939 – March 13th, 1940). Subsequently the city was occupied by the Wehrmacht and remained under siege from 1941 to 1943 when, in the night between September 9th and 10th, the port was finally liberated by the Soviet army.

Despite the economic crisis experienced by the city of Zdanov (so Mariupol was renamed in October 1948, in honour of Soviet politician Andrei Zdanov, born here in 1896 – it took back the name of Mariupol only in 1989, with the collapse of the Soviet Union), city life resumed and intensified after the war: the port and the Illic factory were connected to the city by new residential districts starting from the 1960s.

Mariupol, theatre of war

A city in independent Ukraine since 1991, the largest agglomeration of Donbas after Donetsk became in 2014 one of the epicentres of the so-called "Russian spring" in eastern Ukraine. In March, following the events of Euromaidan that led to an armed conflict in the Ukrainian territories of Donbas – still ongoing today – demonstrations were held in Mariupol both in support of belonging to Ukraine and in favour of secession. The clashes between Ukrainians and pro-Russian separatists intensified after the proclamation of the Republic of Donetsk (DNR), on April 7th, and at the beginning of May the city effectively passed under the control of the adherents of Novorossija: on April 13th the militants of the DNR managed to besiege the Mariupol city council building and hoist their flag on the roof.

But the siege did not last long and Mariupol managed to escape the fate of becoming the seaport of the self-proclaimed Republic of Donetsk. The city was liberated after exactly two months, on June 13th, 2014, by Ukrainian volunteers from the famous Azov battalion led by Andriy Biletskyi, and has since hosted the Donetsk state administration, also serving as the capital of the Ukrainian region. The siege, the liberation, the demolition of the statue of Lenin, and the life of the citizens of Mariupol between 2014 and 2016 are told in the documentary series City of Heroes (Misto heroiiv).

A key city due to its strategic position, Mariupol remains vulnerable to attacks by separatists (at the beginning of 2015, the port centre was again hit by the DNR missile artillery, which caused a dozen civilian victims) and for this very reason some militarised checkpoints are still in operation in some peripheral and strategic points of the city.

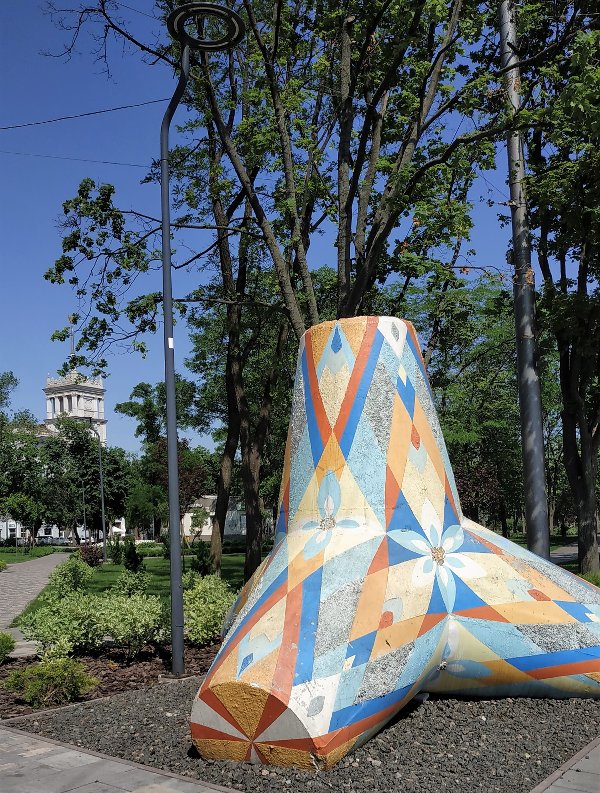

Mariupol’s tetrapods

Anyone who arrives in Mariupol by car, crossing the land checkpoints, cannot help but notice the presence of huge decorated tetrapods guarding the entrances to the city. They can be seen both on country and suburban roads and in the city itself. In times of peace, the tetrapods are 25-ton concrete breakwaters that protect the coast from erosion, but which here became real works of art in 2013. For Mariupol’s 235th birthday celebrations, in fact, the idea of decorating the port city with unusual art objects was born and the tetrapod was chosen as the original symbol of the project. About 80 hand-painted tetrapods with different techniques and colours have been placed in the main squares and streets of the city, thus becoming street art objects.

If few would have thought that a tetrapod would become an art object, no one would ever have considered it an emblem of war. Yet, in times of siege, for Mariupol these impossible-to-overturn breakwaters became fundamental structures for the defence of the city in 2014: some of these concrete giants with painted faces were removed from the squares and transferred to Ukrainian checkpoints, where they still remain.

Lifestyles in today’s Mariupol

The front is less than 20 kilometres from the city, yet the conflict is not in the air today. Visually, there are few memories of the siege: the eastern quarter, bombed on January 24th, 2015, has been restored; the only sign left from the clashes is the burnt city council building, the skeleton covered by a huge banner with the Ukrainian flag and the words "Ukraine is my motherland".

Despite the reconstruction plans, the buildings have not yet been fully restored, but the urban space around them has changed in recent years. There are modern buses and trolleybuses on completely restored streets, families with children strolling through the numerous reconstructed parks and the streets of the centre are teeming with young people and social life, day and night; there is no curfew, like in Donetsk.

Today Mariupol is a quiet port, not even the dreaded ships of the military fleet can be seen on the horizon, but the air remains heavy. Despite the constant tension there is no air of war, but the breeze typical of seaside resorts is missing; you can breathe iron dust, and the city beaches (near the port), although apparently quite clean, are undoubtedly polluted. On the other hand, it cannot be otherwise: the industrial complex managed by the Metinvest Group, owned by oligarchs Rinat Achmetov and Vadym Novynskiy, is the heart of the city, not only employing over 25,000 people, but producing exorbitant turnover for its investors.

Life revolves around polluting factories and the influential Rinat Achmetov is aware of this: the oligarch continues to win the trust of citizens with the modernisation of buildings and infrastructures (one example, the Illicivets sports facility), regardless of the environmental risks to which Mariupol residents are exposed.

Only in the last year has the Illic factory been renovating its facilities to meet international standards on environmental emissions. According to Metinvest, on June 10th the Ukrainian company signed a contract with Italian company Danieli for the supply of equipment for the construction of a new workshop. The investment exceeds one billion dollars and the new plant will be characterised by solutions capable of ensuring that emissions of harmful substances remain 1.5 to 3 times below the maximum permitted standards in Ukraine.

In terms of emissions of harmful industrial substances, Mariupol outdoes any other Ukrainian city: if the Azovstal’ and Illic metallurgical plants, located a few steps from the city centre, are responsible for air pollution, the port is no less dangerous. On its edge appears a mine that literally falls into the sea: ships with loads rich in sulphur, coal pitch and other types of minerals enter the port waters, not always meeting the law’s environmental requirements, and dock a few metres from Pescaniy beach, still popular with citizens and tourists for its central location.

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Sea of Azov: Mariupol’s iron dust

Despite the proximity to the Donbass conflict, there is an air of normalcy in Mariupol, Ukraine. But that very air is heavily polluted by the historic Metinvest metallurgical complex

Mare-d-Azov-la-polvere-di-ferro-di-Mariupol

The industrial area of Mariupol – photo by Claudia Bettiol

Capital of metallurgy and a major port on the Azov Sea with almost half a million inhabitants (the population has been decreasing slightly since 2014), Mariupol is one of the ten largest cities in Ukraine as well as the country’s most important industrial and economic centre. In 2019, the city has conquered the seventh place in the ranking of the most liveable places in Ukraine, despite being a few kilometres from the war front with Russia and the catastrophic ecological situation. The air in Mariupol is, in fact, the dirtiest in the country, there is a pungent smell of formaldehyde and zinc, and you can breathe iron dust.

Background

Since the ninth century, the lands on the Azov Sea hosted trade routes between the countries of the Caucasus and the Slavic lands of Kievan Rus’, which had colonised the steppes of present-day eastern Ukraine (the "dyke pole", wild field, described in the novel Voroshylovhrad by writer Serhiy Zadan). It was along these coasts that Prince Svyatoslav Igorevic, called the Brave, founded the first centre of the region, Bilhorod. Located near Mariupol, the Crimean Tatars later renamed it Bilosaraj (white palace); for this reason the beach near Mariupol still bears the name of Bilosarajska Kosa.

The city centre of what is now Mariupol took shape in the 9th-10th centuries, but only developed in the 16th century thanks to the Zaporizzja Cossacks who aimed to protect trade and roads from invasions from the south. The city was officially founded in 1778, and was named Mariupol by Empress Catherine II in March 1780 in honour of Marija Fedorovna, wife of the future emperor Paul I. In the surroundings, the villages of Bachcysaraj, Yalta, Urzuf, Sartana, and many others were built: all settlements founded by the Greeks who came from the homonymous areas of the Crimean peninsula.

After more than a hundred years under the Russian Empire, on December 30th, 1917 the Soviet power took office in Mariupol and in 1920 the famous metallurgical plants born in the late 19th century "A" ("Nikopol Mariupol") and "B" ("Russian Providence ") were nationalised and merged into a single complex which was named Illic in honor of Vladimir Lenin, in 1924. Together with the metallurgical giant Azovstal’, founded in the 1930s, Illic is today the largest factory not only in the Azov region and in the Donetsk, but also the main metallurgical plant of the former Soviet and present Ukraine. It supplies raw materials (mainly agglomerates) and fully processes and transforms metals (iron, zinc, steel), exporting its products in over 50 countries.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the industrial base of Mariupol adapted to meet the country’s military needs; many workers enlisted, mostly taking part in the winter war between the USSR and Finland (November 30th, 1939 – March 13th, 1940). Subsequently the city was occupied by the Wehrmacht and remained under siege from 1941 to 1943 when, in the night between September 9th and 10th, the port was finally liberated by the Soviet army.

Despite the economic crisis experienced by the city of Zdanov (so Mariupol was renamed in October 1948, in honour of Soviet politician Andrei Zdanov, born here in 1896 – it took back the name of Mariupol only in 1989, with the collapse of the Soviet Union), city life resumed and intensified after the war: the port and the Illic factory were connected to the city by new residential districts starting from the 1960s.

Mariupol, theatre of war

A city in independent Ukraine since 1991, the largest agglomeration of Donbas after Donetsk became in 2014 one of the epicentres of the so-called "Russian spring" in eastern Ukraine. In March, following the events of Euromaidan that led to an armed conflict in the Ukrainian territories of Donbas – still ongoing today – demonstrations were held in Mariupol both in support of belonging to Ukraine and in favour of secession. The clashes between Ukrainians and pro-Russian separatists intensified after the proclamation of the Republic of Donetsk (DNR), on April 7th, and at the beginning of May the city effectively passed under the control of the adherents of Novorossija: on April 13th the militants of the DNR managed to besiege the Mariupol city council building and hoist their flag on the roof.

But the siege did not last long and Mariupol managed to escape the fate of becoming the seaport of the self-proclaimed Republic of Donetsk. The city was liberated after exactly two months, on June 13th, 2014, by Ukrainian volunteers from the famous Azov battalion led by Andriy Biletskyi, and has since hosted the Donetsk state administration, also serving as the capital of the Ukrainian region. The siege, the liberation, the demolition of the statue of Lenin, and the life of the citizens of Mariupol between 2014 and 2016 are told in the documentary series City of Heroes (Misto heroiiv).

A key city due to its strategic position, Mariupol remains vulnerable to attacks by separatists (at the beginning of 2015, the port centre was again hit by the DNR missile artillery, which caused a dozen civilian victims) and for this very reason some militarised checkpoints are still in operation in some peripheral and strategic points of the city.

Mariupol’s tetrapods

Anyone who arrives in Mariupol by car, crossing the land checkpoints, cannot help but notice the presence of huge decorated tetrapods guarding the entrances to the city. They can be seen both on country and suburban roads and in the city itself. In times of peace, the tetrapods are 25-ton concrete breakwaters that protect the coast from erosion, but which here became real works of art in 2013. For Mariupol’s 235th birthday celebrations, in fact, the idea of decorating the port city with unusual art objects was born and the tetrapod was chosen as the original symbol of the project. About 80 hand-painted tetrapods with different techniques and colours have been placed in the main squares and streets of the city, thus becoming street art objects.

If few would have thought that a tetrapod would become an art object, no one would ever have considered it an emblem of war. Yet, in times of siege, for Mariupol these impossible-to-overturn breakwaters became fundamental structures for the defence of the city in 2014: some of these concrete giants with painted faces were removed from the squares and transferred to Ukrainian checkpoints, where they still remain.

Lifestyles in today’s Mariupol

The front is less than 20 kilometres from the city, yet the conflict is not in the air today. Visually, there are few memories of the siege: the eastern quarter, bombed on January 24th, 2015, has been restored; the only sign left from the clashes is the burnt city council building, the skeleton covered by a huge banner with the Ukrainian flag and the words "Ukraine is my motherland".

Despite the reconstruction plans, the buildings have not yet been fully restored, but the urban space around them has changed in recent years. There are modern buses and trolleybuses on completely restored streets, families with children strolling through the numerous reconstructed parks and the streets of the centre are teeming with young people and social life, day and night; there is no curfew, like in Donetsk.

Today Mariupol is a quiet port, not even the dreaded ships of the military fleet can be seen on the horizon, but the air remains heavy. Despite the constant tension there is no air of war, but the breeze typical of seaside resorts is missing; you can breathe iron dust, and the city beaches (near the port), although apparently quite clean, are undoubtedly polluted. On the other hand, it cannot be otherwise: the industrial complex managed by the Metinvest Group, owned by oligarchs Rinat Achmetov and Vadym Novynskiy, is the heart of the city, not only employing over 25,000 people, but producing exorbitant turnover for its investors.

Life revolves around polluting factories and the influential Rinat Achmetov is aware of this: the oligarch continues to win the trust of citizens with the modernisation of buildings and infrastructures (one example, the Illicivets sports facility), regardless of the environmental risks to which Mariupol residents are exposed.

Only in the last year has the Illic factory been renovating its facilities to meet international standards on environmental emissions. According to Metinvest, on June 10th the Ukrainian company signed a contract with Italian company Danieli for the supply of equipment for the construction of a new workshop. The investment exceeds one billion dollars and the new plant will be characterised by solutions capable of ensuring that emissions of harmful substances remain 1.5 to 3 times below the maximum permitted standards in Ukraine.

In terms of emissions of harmful industrial substances, Mariupol outdoes any other Ukrainian city: if the Azovstal’ and Illic metallurgical plants, located a few steps from the city centre, are responsible for air pollution, the port is no less dangerous. On its edge appears a mine that literally falls into the sea: ships with loads rich in sulphur, coal pitch and other types of minerals enter the port waters, not always meeting the law’s environmental requirements, and dock a few metres from Pescaniy beach, still popular with citizens and tourists for its central location.