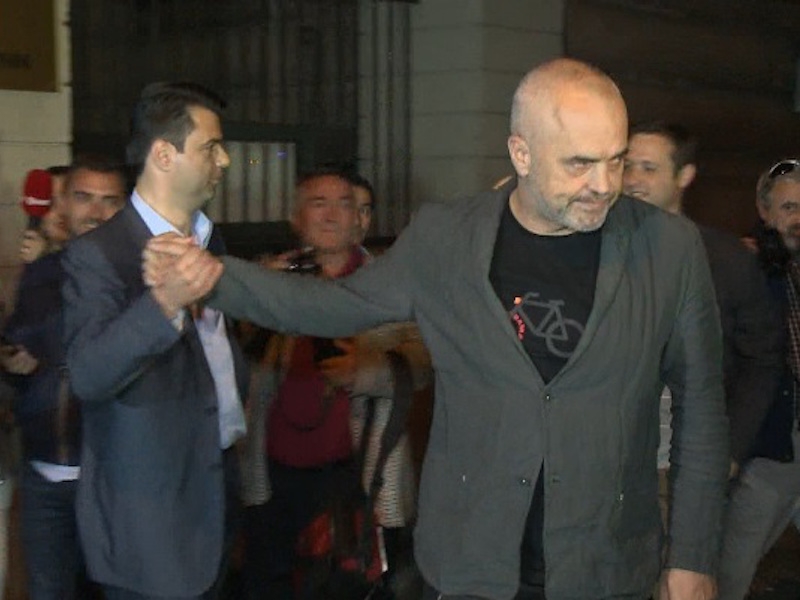

Handshake between Prime Minister Edi Rama and DP Secretary Lulzim Basha

Finally, socialists and democrats found an agreement that will allow regular elections to take place. But at what price? And is the situation really back to "normal"? A comment

Three months after the centre-right opposition took to the streets and the following boycott of parliamentary activities, Lulzim Basha's Democratic Party (DP) and prime minister Edi Rama's Socialist Party (SP) found an agreement to resume parliamentary work, to implement the reform of the judicial system, and to take the country to the next political elections. In exchange for the "return to democracy", the opposition received guarantees including a substantive government reshuffle and a one-week postponement of elections, now scheduled for June 25th.

The agreement and the international mediation

After the parliament boycott, the proclaimed self-exclusion from the upcoming elections, three demonstrations, and several failed mediation attempts, Lulzim Basha's DP finally reached an agreement with the socialist majority on May 18th. A re-opening of the dialogue between the parties was facilitated by the two-day visit in Tirana of Hoyt Brian Yee, US Deputy Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, who put back on the table the previous proposal by German MEP David McAllister, plus a few more concessions by Rama himself. Yee implied that the international community would recognise the Albanian elections even without the participation of the opposition and gave Lulzim Basha a 24-hour ultimatum to comment on the proposal.

A round table with all the parties in the parliament was followed by a private meeting between Rama and Basha. In the early morning, after a trying negotiation, the two leaders announced that they had reached an agreement for the postponement of elections from June 18th to 25th and a new deadline for party registration at the Central Electoral Commission (CEC), which allows for the participation of opposition parties that supported the boycott in recent months.

The reshuffle of the government team was wider than expected. Edi Rama remains in office as prime minister, but the opposition will appoint his deputy prime minister and six crucial ministers – Interior, Justice, Education, Finance, Health, and Welfare. However, the agreement prescribes that these names will be selected among "technicians" rather than prominent right-wing political figures. In addition, the former "opposition" was granted the presidency of the Central Election Commission and the appointment of the new National Ombudsman – institutions with a key role in the management of the electoral process and the judicial reform. Here, however, the choice failed to meet the technical criterion, as the new chairman of the CEC is Klement Zguri, who already represented the DP in the Commission, while the Ombudsman is Erinda Ballanca, former lawyer of Lulzim Basha and of former Democratic Prime Minister Sali Berisha. In exchange for such a booty, the DP pledged to resume parliamentary work, especially within the parliamentary committees set up for the implementation of the judicial reform, so far inactive because the opposition had not appointed its representatives.

Finally, in the week following the agreement, the Criminal Code was immediately amended to increase penalties for election offences – particularly for trafficking votes – and to strengthen the legal framework for regulating and limiting the electoral expenses of parties and for increasing transparency. The electoral reform and the introduction of an electronic system for identification, voting, and counting votes were instead postponed to the 2021 elections. Once the agreement was reached and announced, the two leaders gave each other a high five and both shouted the victory, while and the DP removed the tent that had occupied the square in front of the Presidency since February 18th. The following day, congratulations came from the international community for the "democratic maturity" demonstrated.

Contradictions

The agreement of May 18th, negotiated urgently and only between the two main parties, revealed all the contradictions and inconsistencies of the Albanian political class. In a few hours, the two major leaders gave up on positions they had called "non-negotiable" over the last three months.

At every meeting and negotiation table, Lulzim Basha had called for Rama's resignation, promising a "New Republic" as the only way to ensure free and fair elections. Rama, for his part, accepted postponing the election date, until then regarded as unjustified and inadmissible, and handed over the guidance of most state institutions, in the most delicate sectors. Before, he had always stated that mandates and appointments are not privileges, but responsibilities, that can be stripped from state representatives only through the popular vote.

During the talks of May 18th, Ilir Meta's ears must have been ringing, as the leader of the Socialist Movement for Integration (SMI) was once again excluded from negotiations – just like in 2008, for the agreement between Rama and Sali Berisha, then president of the DP. The new found agreement between SP and DP has further crippled internal relations within the SP-SMI coalition, winner of the last elections, that now no longer exists. If registrations at the Central Election Commission were reopened arbitrarily, for the sole purpose of enabling the opposition parties to be registered, this was not the case for coalitions – all parties will compete on their own for proportional distribution of seats. As always, given the thresholds, smaller parties will bear the brunt of this choice.

Signed a month before the elections, the Rama-Basha agreement feels like a "dress rehearsal" for a post-electoral "big coalition" between the two major parties. The government that came out of the reshuffle is formed by 10 representatives of the SP, 7 of the DP, and 4 of the SMI. The one that could come out of the polls may rest on the reconfirmed collaboration between socialists and democrats in order to leave aside the SMI, weakened by the electoral system and by the presidential exile of its leader Ilir Meta, already "quarantined" by the political system.

Change the rules, not the politics

Political scenarios and calculations aside, Tirana's latest crisis has made it clear that Albanian political parties continue to bring dialogue away from institutions and, above all, outside the Parliament which, by constitution, should host the political confrontation. Although the body of the Constitution has not been formally altered, discussing laws in private rooms and in absolute lack of transparency, as well as changing the rules just before the elections, certainly betrayed its spirit. For the leaders of both sides, the Constitution remains alien to the country's political life – not the document that moulds the divergences between parties into shared solutions, but a piece of paper that can be overwritten whenever factions find it convenient.

These three months of stalemate have also shown how this political class continues to rely on the role of international mediators to uphold their legitimacy, choosing to delegate to Brussels or the United States those responsibilities that the vote entrusted to the political parties.

No, the agreement of May 18th did not end the crisis. The voters who will go to the polls will find all the parties of democratic Albania on the sheets, but this will not mean that they have more choice.

To Top

To Top