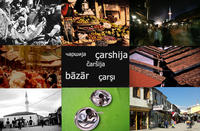

The Kruja bazaar - photo by Marjola Rukaj

Having survived for thousands of years, nearly disappeared at the beginning of the 20th Century and been brought back to life during the regime, the Bazaar of Derexhik in Kruja, Albania, is today a boutique for tourists. Despite the loss of traditions, unregulated urban growth and rampant globalisation, it continues to survive in its true spirit

“Kruja is a strange town, all clustered around its bazaar.” This phrase was often repeated in the travel notes of last century's Western adventurers. On the list of most visited places in Albania this town is never missing. But its urban form has changed over time and the bazaar been reduced to a single, long street which has survived thanks to the interest of the authorities, both during Enver Hoxha's regime and after its downfall.

Only 32 kilometres from the capital, the town is easy to reach on local transport, going along new, modernized roads which link Tirana to the north of the country, at first on the flat then rising steeply through the trees. The town can be seen from a distance with its medieval castle and the museum of Skanderbeg, built during Enver Hoxha's regime in memory of the Albanian national hero, 500 years after his death. Skanderbeg was in fact from these parts and Kruja was a strategic point in the anti-Ottoman resistance. Little is left of the Skanderbeg castle, but the fact that it is tied to the legend of the hero who fought against the Turks for about 25 years has meant that the town gained the attention of those in power from the early 60s. And so the castle and the Ottoman bazaar which connects it with the busy, modern part of the town have become some of the most highly regarded places in the country's heritage.

The bazaar has a truly oriental look, multi-coloured and overflowing with goods of every description. A typical Ottoman market right before our eyes. But it is only a small part of what it once was when Western travellers described it, fascinated, as a piece of Istanbul close to the Adriatic Sea. Early on in the 1900s various sources testify to the Kruja bazaar having about 150 shops of different kinds, including craftsmen and producers of all the goods needed in the town. The inhabitants call it the Bazaar of Derexhik (Pazari i Derexhikut), that is the bazaar of the stream, in Turkish, owing to the many streams in the area, so many that even the name of the town itself is said by qualified linguists to derive from the term krua, which means stream in Albanian.

Today the Derexhik Bazaar has only 60 or so shops which function merely for tourists. Despite its small size and limited social use for the town, the bazaar is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country. Tourist agencies usually offer a short stop in the town combined with an overnight stay in Tirana. The tourists are numerous, the shopkeepers seem satisfied and optimistic.

“I have to thank Enver Hoxha” says Hysen who makes shajak, a material produced from beaten wool used in that area for manufacturing winter clothes, shoes and the traditional white hat, the plis. “It was during the regime that I was told to drop everything and take up my family tradition again. My family had made shajak for generations but during my youth the bazaar was dead and I worked as a mechanic in a state garage. Then at a certain point it was decided to set it up again and we went back to our family tradition. My forebears worked two doors away.” Unlike many other Albanian çarshijas * where the bulldozers got the best of it, in the name of modernity and in the form of concrete, Kruja was chosen as an example of Ottoman life to be saved and reinvigorated, to be promoted culturally and for tourism. The fact that the town was linked to the name of Skanderbeg and his centrality to Albanian history and national-communist mythology naturally played a fundamental role in the decision not to abolish it.

In about 1966 the Hoxha regime began to rebuild the disintegrating çarshija. At that time the Derexhik was reduced to a muddy alley with a couple of shops mainly selling basic goods. The Hoxha regime implemented the plan to reconstruct the shops and kaldrem, the stone surface typical of all the Ottoman roads before asphalt reached the Balkans.

Now the architectonic structure seems to reflect faithfully the Ottoman one, apart from bits of concrete wall sticking out here and there, a tolerated illegality, part of the wave flooding the whole of Albania in recent years. Many craftsmen were trained by the regime to enable them to continue their family traditions. In the çarshijas in Ottoman times the craftsman's skills were handed down in the family. The advent of communism and the move from feudalism to a planned economy contributed to the loss of this tradition. The craftsmen's shops in Kruja were taken over by the state and became simply sales counters for what was produced in state-run crafts industries. Sons of craftsmen, encouraged to follow in the family tradition, were taken on in these state-run factories today still called Artistic Industries by the local people. The collapse and privatization of the state-run industries in the early 90s did not spare the workers at the 'Artistics' who are now to be found employed in or running the shops in the Derexhik Bazaar.

Reconstructing traditions is however proving difficult: it has been almost impossible to establish the historical connection formed over generations with the place where the craftsmen now make and sell their products. After privatization the shops were sold off to private individuals and the way this transition happened is something many people prefer to overlook, explaining that they were not the first owners but took over the shop after it had already been privatized, or they have been taken on as employees of others. Thanks to the large numbers of tourists, a small shop in the bazaar allows its owner to lead a dignified life in a changing Albania.

Notwithstanding the global economic crisis of recent years, tourists buy souvenirs in Kruja. The market offers local products such as kilims, beautifully embroidered traditional costumes, wooden ornaments, but goods coming from Turkey and China are also common. From this point of view there is little difference between the Kruja market and ordinary souvenir shops. In recent years however, with the arrival of tourists, people are realising that globalised souvenirs from China and Turkey are not very good business cards. At times compromises are reached, for example by commissioning typical Albanian products in China. With surprise you may see that the Albanian flag or wooden scenes of Albania have the trademark “made in China”.

Among the souvenirs bunker-shaped ashtrays, key rings with the Albanian flag and even cups with the photo of Prime Minister Berisha and the dictator Enver Hoxha side by side do not go missing. These are the products that sell best in a time of global crisis, while, on the other hand, the tourists from the former Soviet Union and from Northern Europe prefer to buy the Skanderbeg cognac. Among the many shops there are only a few craftsmen who sell material collected from inhabitants of the surrounding area as well as displaying their own products. Every so often one glimpses someone working the shajak, dressmakers sewing the complex traditional costumes and kilim weavers with their white, red and black designs. All these people are over fifty and considered the last generation to do this laborious and badly paid work. “The young people aren't interested, they prefer working in the foreign investors' factories, full of toxic matter,” one hears said. However from time to time it is stated that the demand for traditional products is increasing. “In recent years there's been a growing tendency to wear traditional costumes for weddings and various festivals. For example, Albanian girls today prefer wearing a traditional wedding dress for at least one day during the ceremony. And traditional kilims are to be found in houses and increasingly prized,” says an embroiderer at the entrance to the bazaar.

The local authorities seem less pessimistic about the difficulties facing the traditional occupations and state their intention to set up a technical school to teach the skills which are in danger of dying out, so as not to lose these traditions and to give a more authentic feel to the Kruja bazaar. This project could be put into practice through a grant from the European Union. The establishment of such a centre will be crucial for Kruja which, today, as in the past, owes most of its resources to the bazaar.

The shops, goods everywhere on display, helpful but discreet salespeople, all make the Derexhik in Kruja a must if one wishes to see a sample of Ottoman culture in Albanian style. But even this bazaar is submerged in the chaotic Albanian urban scene, typical of the rest of the country. “This town is now a concrete village,” say many of its citizens, showing their discomfort for the building expansion which surrounds the bazaar. Big buildings go up one on top of another defying any possible criteria of town planning. Despite this, Kruja and its bazaar remain a focal point of Albanian cultural tourism. A point of strength which can only be developed if the challenges of globalisation and unregulated urbanisation are met.

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.