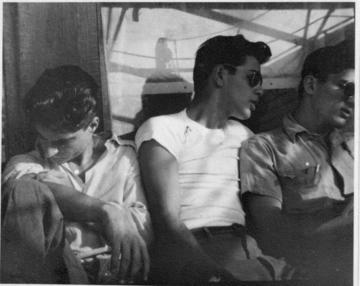

Passeggeri rimpatrianti durante un'esercitazione di sicurezza sulla Sobieski nel 1949. Immagine di Crosby Phillian.

A group of 162 American-Armenians on a journey form New York towards Armenia in 1949 stops in the port of war-torn Naples. Women and men who soon afterwards would be living in Stalin's USSR are astonished by the misery they see in post war Italy

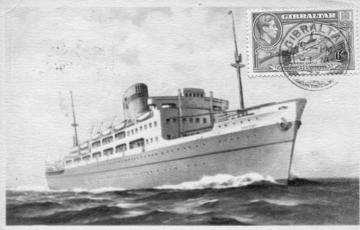

Twenty-five years to the day of the death of the father of the Bolshevik Revolution, V.I. Lenin, the Sobieski set sail from New York, on January 21, 1949, to Naples, its final port of call. The repatriates were leaving the United States for Soviet Armenia. After surrendering their American citizenship papers, they set sail as Soviet citizens on the Polish transatlantic passenger ship. The ship was navigating the same route of the Rossiya, the Russian-confiscated German ship that took the first group of American-Armenians to Batumi in the Fall of 1947. One-hundred and sixty-two of the little over 300 American-Armenians repatriates were part of the second caravan leaving America for Soviet Armenia after World War II. Despite efforts by those who left on the first caravan to warn family and friends about their impending fate, the 162 American-Armenians made the same unfortunate voyage.

The 162 were originally going to set sail late in 1948, on the Pobeda, the ship that was instrumental in the repatriation of Armenians from France, Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine and Iraq. 1 However, in September of 1948, a fire damaged the ship, the cause of which was unknown. After a closed-door trial, it was later reported that the captain of the Pobeda, the telegrapher, and the dispatcher were all pronounced guilty of negligence. Two weeks after the event occurred, Soviet leader Josef Stalin laid acrimonious blame upon the Americans, consequently effecting Soviet regulation to “completely and immediately” 2 desist the further repatriation of Armenians from the Diaspora. An exception was made less than a month later, where, in the end, the 162 American-Armenians became the last group to repatriate. 3

Pictures

Postcards, dinners, group photos. The journey of American-Armenian repatriates aboard the Sobieski in 1949. A photo gallery. Images courtesy of Crosby Phillian

When a number of the ship’s passengers disembarked at various times at the three ports of call before Naples, the 162 American-Armenian “repatriates” remained on board. Repatriate Sonia Meghreblian recalls in her published memoir 4 a brief first stop at Gibraltar where several vendors boarded the ship to sell souvenirs. The next entry port for the ship was in France at Cannes. There, one passenger was allowed off the Sobieski, who went ashore on a small boat. After a few hours in Cannes, the ship headed for Genoa, where again other passengers left the ship, while the repatriates remained onboard. The last stop was at Naples.

Naples

It was at the port of Naples where the repatriates soon sensed that their relatively adventurous journey had ended and they faced a foreboding situation as they headed toward their final destination. Largely ignorant of the devastating effects of World War II in Europe, the American-Armenians would soon witness the extremes of poverty. Beginning first in Naples, the prosperous world of experienced reality by the American-Armenians collided with the surrealism of post-WWII destruction in Europe. As non-repatriate passengers disembarked, the American-Armenian passengers remained on the Sobieski, awaiting further word about plans to change ships.

The sketchy logistical travel plan for the 162 repatriates was to first bring them to Naples on the Polish passenger ship and then have them transfer to the Ardeal, a Romanian cargo ship. The transfer of passengers did not proceed as planned. The Ardeal did not enter the Naples port as anticipated. The reason remains unclear, but many assumed that when the Soviets and Romanians learned of the presence of the United States Navy, the Ardeal remained at sea to avoid an international incident. The politically awkward affair left the repatriates in an indeterminate state of transport.

From James Dean to Stalin: the tragedy of the Armenian repatriation

As a young child, she always wondered why she lived in Yerevan when her father was born in the U.S. and her mother was from Lyon. Then she understood. With an historical-artistic project, Hazel Antaramian Hofman follows the footprints of those people, who, from all over the world, decided to migrate to Armenia after the Second World War. Read her article: From James Dean to Stalin: the tragedy of the Armenian repatriation

With no official papers to set foot on Italian soil, the situation was quite precarious. Adding to the dilemma was the presence of the Sixth Fleet of the United States Navy docked in Naples. At the conclusion of World War II, Italy faced trying economic devastation. The Treaty of Peace with Italy in 1947 rendered the country’s prior international standing lifeless. Disarmament clauses and imposed reparations to various countries, including the Soviet Union, created economic and political turmoil for Italy. 5 According to Crosby Phillian, a fifteen-year old New Yorker heading to Soviet Armenia with his family, among the warships in the Naples port was the aircraft carrier, the USS Philippine Sea. He also recalls that the fleet was granted shore leave. He saw boat loads of sailors traversing between ship and shore and back. 6

After a few days, the Soviets decided to allow the repatriates off the ship while waiting out the situation. Before boarding buses to the Hotel Grilli, the repatriates were allowed a sequestered sojourn while awaiting their transfer. They walked in military fashion from the ship to the buses. On one side of the single-filed line of repatriates was a Soviet official and on the other side was an Italian official. 7

During their time in Naples, the repatriates witnessed extreme situations of poverty. Meghreblian, a nineteen year-old at the time, noted the devastation caused by the war. They saw locals living in bomb-shelled buildings. 8 Phillian remembers an incident on the wharf that spoke to severe shortages:

The stevedores were unloading a cargo net when one of the sacks burst open. It was sugar! All of a sudden there was a swarm of people, I don’t know where they came out from, scooping up the spilt sugar with their bare hands and putting it into bags. When you have never seen anything like that, it leaves a very deep impression on you. Who would scoop up spilt sugar with their bare hands in the United States? You never even thought about things like that. 9

Unbeknownst to the repatriates, this incident foreshadowed their own upcoming plight in Soviet Armenia. Another teenage American-Armenian repatriate from Watertown, Massachusetts, Deran Tashjian, indicated that after experiencing the poverty in Naples some of the repatriates finally began to question their future predicament. 10

The 162 stayed at the hotel in Naples for nearly a week. Phillian said that at every entrance to the hotel, there was “an armed soldier standing guard.” The “captive guests” whiled away the time by reading, talking, and playing poker. At the hotel there was a barber, so some of the repatriate men took the opportunity to get their hair cut. Phillian noted how with only a pair of scissors and a comb the man worked “like an artist…for only 50 cents,” a bargain for the Americans.

When word was received that the Sixth Fleet had left Naples, the Ardeal made its way into port to retrieve the repatriates. With the same ‘military escort,’ the repatriates were taken from the hotel to the port. They were counted again to assure that everyone who had originally disembarked the Sobieski for the hotel was there to board the Ardeal. Like day and night, for the passengers, no reasonable comparison could be made between the Sobieski and the Ardeal. The repatriates arrived in Naples on a passenger ship with comfortable amenities, and left Italy on a “squat ugly-looking cargo ship with no accommodations for all…who were to board it.” 11 With only a few cabins assigned to the women, children, and the elderly, the mess hall during the day was converted to a large sleeping area at night for the men. After the Ardeal left Naples, it moved passed Sicily, up along the Greek Islands and headed toward Romania. While passing through the Dardanelles to enter the Black Sea toward Batumi, the repatriates confronted Turks sailing the waters in rowboats. Insults were exchanged between the repatriating American-Armenians and the Turks, whereby the Turks gestured with a “sign of cutting the throat.” 12 In retrospect, Phillian says that he was not too sure if this gesture had more to do with the animosity between the two peoples, or more reflective of the plight that the American-Armenians would be facing as they “returned” to Soviet Armenia.

The Ardeal eventually docked in Constanza, a port on the Black Sea that once flourished as a trading port between the Byzantine Empire and Italian ports during the tenth and eleventh centuries. A number of officials came on board the Ardeal, but only the Romanian-native sailors were allowed to go ashore. Phillian tells of an interesting event that took place on the Ardeal between an American-Armenian and a Romanian-Armenian sailor. The sailor spoke Armenian and was approached by one of the repatriates to help send a letter back to the United States. Since Romania was under the political yoke of the Soviet Union at this time, the sailor was concerned with communist officials who conducted routine searches. Cautiously the sailor refused to deliver the letter; he knew that he would be searched by Romanian authorities when leaving the ship and then again before boarding. 13 This was probably a wise move for the safety of the repatriates as well. It was not uncommon for many American-Armenians to be under suspicion of American espionage, a real concern for many American-Armenians once on Soviet land. Many were later interrogated and tortured by the Soviet Committee for State Security, better known as the KGB, its Russian acronym.

From Romania, the ship arrived at its final destination in Batumi, a port in Soviet Georgia, where they were awaited by a delegation as well as family members who had arrived in 1947. The landing was filled with propaganda-driven speeches and political fanfare. The 162 American-Armenian repatriates were soon taken to a hangar where again they awaited the final stage of their ill-fated journey to Soviet Armenia.

1 The Armenian General Benevolent Union, One Hundred Years of History, Vol. II, 1941-2006, AGBU, Central Board of Directors, Paris, 302.

2 Armenian General Benevolent Union, “Realizing a Dream: Then and Now,” Vol. 20, No. 2, November 2010, 6.

3 AGBU, “Realizing a Dream,” 6.

4 Sonia Meghreblian, An Armenian Odyssey, Gomitas Institute, 2012.

5 John B. Hattendorf, Naval Policy and Strategy in the Mediterranean Sea: Past, Present and Future, Routledge Publisher, 2000, 198. The pressure by the peace treaty lessened its impact as the West drew Italy more within its sphere. See Roy Palmer Domenico, Remaking Italy in the Twentieth Century, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., New York, 2002, 108.

6 Phillian, letter to author, September 19, 2012.

7 Phillian, letter to author, September 19, 2012.

8 Meghreblian, An Armenian Odyssey, 2012, 76.

9 Phillian, letter to author, September 19, 2012.

10 Tashjian, personal interview with author, July 8, 2012.

11 Phillian, letter to author, September 19, 2012.

12 Phillian, letter to author, September 19, 2012.

13 Phillian, letter to author, September 19, 2012.

To Top

To Top