In memory of Bayram Mammadov, a young man full of dreams

Bayram Mammadov was a young Azerbaijani activist who was unjustly imprisoned in 2016 and then released on presidential amnesty. Since 2020 he had been in Istanbul for his studies. On May 2 he was found dead in the Turkish city. His story

In-memory-of-Bayram-Mammadov-a-young-man-full-of-dreams

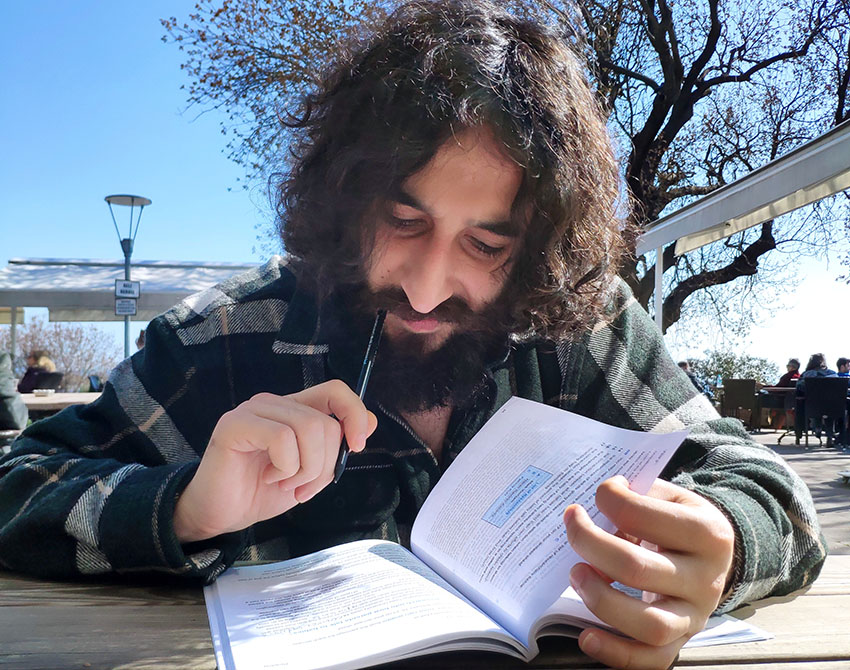

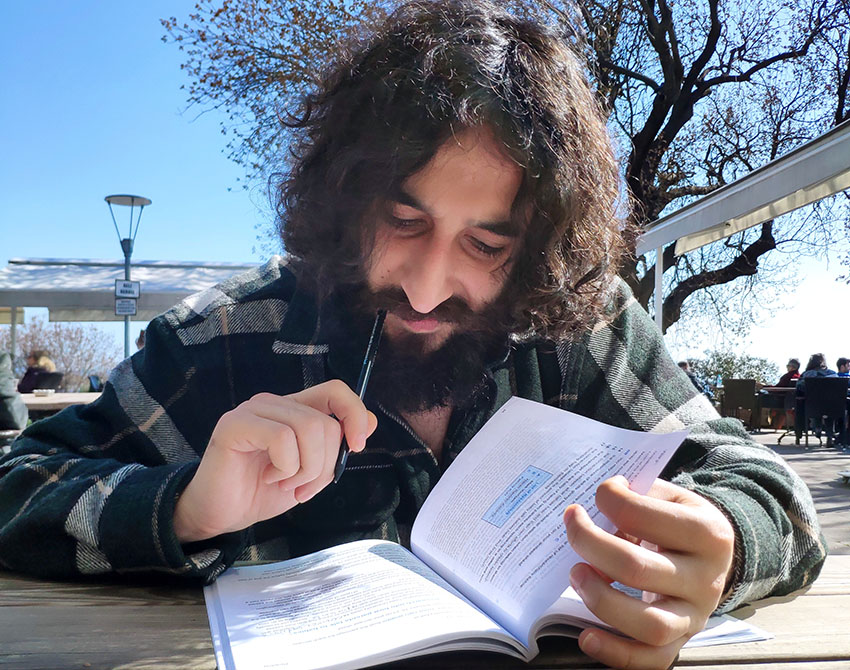

Bayram Mammadov - photo © Vahid Aliyev

I have only written an eulogy once. It was for my father who passed away in 2012. This is different. Writing about someone who was still so young and had big plans is hard. Here is the story of a young activist from Azerbaijan, who was found dead in Istanbul on May 2.

Scrolling through countless posts dedicated to Bayram on social media, one cannot help but rage with anger, not only because Bayram was only 26 when he died, but because he was put through so much agony for his views and activism that it sends shock waves down one’s spine.

“Bayram was not like everyone else”, wrote former political prisoner Anar Mammadli on Facebook. “He had a special place among all other youth activists. He was not populist. He self-criticised himself often, and worked hard to study abroad”, Mammadli continued.

“In this country, and in general anywhere in the world, progress is only possible thanks to people like Bayram […] If it wasn’t for people like Bayram, cheats would keep getting away. Bayram’s place in the history of progress is eternal”, wrote academic Altay Goyushov.

“You were a good friend, full of energy, principled human being. It should not have been this way”, shared activist Ulvi Hasanli on Facebook.

“What killed Bayram was the pain and trauma. None of us could imagine what he witnessed, and was put through in prison. He never considered himself a witness. He never talked about the torture. Those who have destroyed his mental health are the ones who dragged him to death”, wrote researcher and author Bahruz Samadov.

I met Bayram during his jail sentence. He was one of the two graffiti prisoners. He was arrested in May 2016, after spraying graffiti on the statue of former president Heydar Aliyev. The graffiti read "Happy Slave Day" in Azeri — a play on the phrase "Happy Flower Day", Azerbaijan’s national holiday that coincides with Heidar Aliyev’s birthday – on one side of the statue and “Fuck the system” on the other.

Following his arrest on May 11, Bayram was beaten by the police officers. On May 12, he was sentenced to four months in pretrial detention on spurious drug charges. Later, in his statement, Bayram described at length and in detail the torture he endured.

In his testimony , Bayram wrote that, after being forced into a car by three men he had never seen before, he was brought to Sabuncu Police Department and Temporary Detention Center, where he was beaten by seven or eight men who were not wearing police uniforms. As they beat him, the men kept asking him why he took pictures of the graffiti and who his associates were. But Mammadov was unable to respond: he lost consciousness soon after. “They beat me harder and demanded that I accept the charges [drug charges]. They swore at me and insulted me. They took my pants off and threatened to rape me with a baton. I had no choice but to accept the charges, confess and sign the testimony that was handed to me”.

On December 8, 2016 Bayram was sentenced to ten years in jail on bogus drug possession and trafficking charges. In a statement issued the same day, Amnesty International Deputy Director for Europe and Central Asia Denis Krivosheev describes charges as “clearly fabricated” in order to punish him for his activism. “This outrageously long sentence following already prolonged, unnecessary and arbitrary detention is a blow to all peaceful activists in Azerbaijan”.

Giyas Ibrahimov received a similar sentence. The two served jail time despite numerous calls for their immediate release.

Bayram and Giyas were released in 2019, with a presidential pardon. What an irony – the son of the president whose statue the activists sprayed pardoned them after stealing three years of their lives and inflicting insurmountable damage, only to get praised later for his mercifulness.

On February 13, 2020, the European Court of Human Rights ruled unanimously that there was a violation of Articles 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment), 5.1 (right to liberty and security), 5.4 (lawfulness of detention), 10 (freedom of expression), and 18 (improper use of restrictions in the Convention) in conjunction with Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The international court also obliged Azerbaijan to pay each applicant 30,000 Euros for non-pecuniary damage and 6,000 for costs and expenses.

Bayram was planning to spend the money on the education abroad he very much dreamt of, and so he went to Istanbul.

Istanbul Chapter

In November 2020 Bayram relocated to Istanbul, where he rented a flat in the Kadikoy district and applied for a residence permit. He took English language classes and was preparing for IELTS exams, required for most graduate school applications. He was applying to universities. “I wrote several letters of recommendation for Bayram. He was still waiting to hear from Chevening [scholarship programme] and applied to universities in Canada and to the Central European University [in Hungary]. He wanted to spend the compensation he won at the European Court of Human Rights on his education”, told me Anar Mammadli in an interview.

Bayram believed in good education, his friends say. Many of those who wrote about him on Facebook said he wanted to get a good education and return to Azerbaijan to help others and to do good.

Bayram was last seen on April 29. He met with Elgiz Gahraman, another former political prisoner he had met in jail. The two stayed in touch until May 2. Then, Bayram stopped answering calls and messages. Another friend, Vahid, who did not hear back from Bayram after calling him on May 3 and 4, later called Elgiz to ask whether he had seen or talked to Bayram. Elgiz had not. On May 4, a group of Bayram’s friends visited his flat, where they found all of his belongings in place, including his mobile phone and ID. They thought he may have gone out and would be back, as it was getting close to 5pm (Turkey went into a country-wide strict lockdown on April 29 with curfew at 5pm). When Bayram did not show up, they decided to call the police and file a missing person report.

On the phone, police told Elgiz that they would only register the missing person report if filed in person by a first-degree relative. Since this was not an option, Elgiz went to the police station anyway. He was redirected to a different police station in Kadikoy, where he stated that his friend was missing and that they had had no news of him since May 2. He showed Bayram’s picture to the police. Officers on duty then informed Elgiz that they had found the body of a John Doe on May 2 in Moda (a water front in the same district). When Elgiz saw the pictures, he confirmed it was Bayram.

After identifying Bayram, Elgiz tried to get more information – was he taken to a morgue, was there an autopsy, was he already buried, what was the cause of death? But police officers told him they had no further information except an eyewitness report that Bayram jumped into the water to fetch his slippers and drowned after swimming 20-25 metres away from the shore. The officers told Elgiz to come back the following morning.

On May 5 Elgiz, together with other friends, returned to the police station. At first, he was told that there had been a misunderstanding and he had been given false information – they did not know where Bayram’s body was. Eventually, they did say Bayram was at the morgue.

While we all wait for further updates, I am thinking of Bayram, his family, his friends. He would have had a very different life, had he not been unjustly arrested and thrown in jail under false pretext. He would not have been tortured, threatened with rape, beaten, and insulted. He would have stayed a young man full of hopes and aspirations. And this is how I would like to remember him.

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

In memory of Bayram Mammadov, a young man full of dreams

Bayram Mammadov was a young Azerbaijani activist who was unjustly imprisoned in 2016 and then released on presidential amnesty. Since 2020 he had been in Istanbul for his studies. On May 2 he was found dead in the Turkish city. His story

In-memory-of-Bayram-Mammadov-a-young-man-full-of-dreams

Bayram Mammadov - photo © Vahid Aliyev

I have only written an eulogy once. It was for my father who passed away in 2012. This is different. Writing about someone who was still so young and had big plans is hard. Here is the story of a young activist from Azerbaijan, who was found dead in Istanbul on May 2.

Scrolling through countless posts dedicated to Bayram on social media, one cannot help but rage with anger, not only because Bayram was only 26 when he died, but because he was put through so much agony for his views and activism that it sends shock waves down one’s spine.

“Bayram was not like everyone else”, wrote former political prisoner Anar Mammadli on Facebook. “He had a special place among all other youth activists. He was not populist. He self-criticised himself often, and worked hard to study abroad”, Mammadli continued.

“In this country, and in general anywhere in the world, progress is only possible thanks to people like Bayram […] If it wasn’t for people like Bayram, cheats would keep getting away. Bayram’s place in the history of progress is eternal”, wrote academic Altay Goyushov.

“You were a good friend, full of energy, principled human being. It should not have been this way”, shared activist Ulvi Hasanli on Facebook.

“What killed Bayram was the pain and trauma. None of us could imagine what he witnessed, and was put through in prison. He never considered himself a witness. He never talked about the torture. Those who have destroyed his mental health are the ones who dragged him to death”, wrote researcher and author Bahruz Samadov.

I met Bayram during his jail sentence. He was one of the two graffiti prisoners. He was arrested in May 2016, after spraying graffiti on the statue of former president Heydar Aliyev. The graffiti read "Happy Slave Day" in Azeri — a play on the phrase "Happy Flower Day", Azerbaijan’s national holiday that coincides with Heidar Aliyev’s birthday – on one side of the statue and “Fuck the system” on the other.

Following his arrest on May 11, Bayram was beaten by the police officers. On May 12, he was sentenced to four months in pretrial detention on spurious drug charges. Later, in his statement, Bayram described at length and in detail the torture he endured.

In his testimony , Bayram wrote that, after being forced into a car by three men he had never seen before, he was brought to Sabuncu Police Department and Temporary Detention Center, where he was beaten by seven or eight men who were not wearing police uniforms. As they beat him, the men kept asking him why he took pictures of the graffiti and who his associates were. But Mammadov was unable to respond: he lost consciousness soon after. “They beat me harder and demanded that I accept the charges [drug charges]. They swore at me and insulted me. They took my pants off and threatened to rape me with a baton. I had no choice but to accept the charges, confess and sign the testimony that was handed to me”.

On December 8, 2016 Bayram was sentenced to ten years in jail on bogus drug possession and trafficking charges. In a statement issued the same day, Amnesty International Deputy Director for Europe and Central Asia Denis Krivosheev describes charges as “clearly fabricated” in order to punish him for his activism. “This outrageously long sentence following already prolonged, unnecessary and arbitrary detention is a blow to all peaceful activists in Azerbaijan”.

Giyas Ibrahimov received a similar sentence. The two served jail time despite numerous calls for their immediate release.

Bayram and Giyas were released in 2019, with a presidential pardon. What an irony – the son of the president whose statue the activists sprayed pardoned them after stealing three years of their lives and inflicting insurmountable damage, only to get praised later for his mercifulness.

On February 13, 2020, the European Court of Human Rights ruled unanimously that there was a violation of Articles 3 (prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment), 5.1 (right to liberty and security), 5.4 (lawfulness of detention), 10 (freedom of expression), and 18 (improper use of restrictions in the Convention) in conjunction with Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The international court also obliged Azerbaijan to pay each applicant 30,000 Euros for non-pecuniary damage and 6,000 for costs and expenses.

Bayram was planning to spend the money on the education abroad he very much dreamt of, and so he went to Istanbul.

Istanbul Chapter

In November 2020 Bayram relocated to Istanbul, where he rented a flat in the Kadikoy district and applied for a residence permit. He took English language classes and was preparing for IELTS exams, required for most graduate school applications. He was applying to universities. “I wrote several letters of recommendation for Bayram. He was still waiting to hear from Chevening [scholarship programme] and applied to universities in Canada and to the Central European University [in Hungary]. He wanted to spend the compensation he won at the European Court of Human Rights on his education”, told me Anar Mammadli in an interview.

Bayram believed in good education, his friends say. Many of those who wrote about him on Facebook said he wanted to get a good education and return to Azerbaijan to help others and to do good.

Bayram was last seen on April 29. He met with Elgiz Gahraman, another former political prisoner he had met in jail. The two stayed in touch until May 2. Then, Bayram stopped answering calls and messages. Another friend, Vahid, who did not hear back from Bayram after calling him on May 3 and 4, later called Elgiz to ask whether he had seen or talked to Bayram. Elgiz had not. On May 4, a group of Bayram’s friends visited his flat, where they found all of his belongings in place, including his mobile phone and ID. They thought he may have gone out and would be back, as it was getting close to 5pm (Turkey went into a country-wide strict lockdown on April 29 with curfew at 5pm). When Bayram did not show up, they decided to call the police and file a missing person report.

On the phone, police told Elgiz that they would only register the missing person report if filed in person by a first-degree relative. Since this was not an option, Elgiz went to the police station anyway. He was redirected to a different police station in Kadikoy, where he stated that his friend was missing and that they had had no news of him since May 2. He showed Bayram’s picture to the police. Officers on duty then informed Elgiz that they had found the body of a John Doe on May 2 in Moda (a water front in the same district). When Elgiz saw the pictures, he confirmed it was Bayram.

After identifying Bayram, Elgiz tried to get more information – was he taken to a morgue, was there an autopsy, was he already buried, what was the cause of death? But police officers told him they had no further information except an eyewitness report that Bayram jumped into the water to fetch his slippers and drowned after swimming 20-25 metres away from the shore. The officers told Elgiz to come back the following morning.

On May 5 Elgiz, together with other friends, returned to the police station. At first, he was told that there had been a misunderstanding and he had been given false information – they did not know where Bayram’s body was. Eventually, they did say Bayram was at the morgue.

While we all wait for further updates, I am thinking of Bayram, his family, his friends. He would have had a very different life, had he not been unjustly arrested and thrown in jail under false pretext. He would not have been tortured, threatened with rape, beaten, and insulted. He would have stayed a young man full of hopes and aspirations. And this is how I would like to remember him.