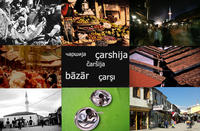

Bazaar Rhythms

Cultural and ethnic crossroads and meeting place par excellence, the çarshija is also the place for finding some of the deepest roots of the Balkan musical heritage. Our inquiry

Fast rhythms and harmonies that make even those who know absolutely nothing about traditional dancing dance. But the melodies can also be slow, mournful or sentimental. The Balkan musical legacy goes well beyond the label which world music has given it: it is not just this exotic version, but a result of the cultural and ethnic crossroads which the Balkans have been for centuries.

Elements from Eastern Europe, Turkish and Middle Eastern rhythms, with here and there a touch of Western music, have all been woven together in an organic way and much of that heritage was synthesized in that special meeting place, the čaršija or traditional Bazaar.

Not only Ottomans

What distinguishes the Balkans musically from the rest of Europe is precisely the coexistence of many elements of a different nature and an enormous variety of rhythms: an Oriental flavour which makes us think of the Ottoman Empire, for centuries an open area without internal barriers and characterized by continuous migration and communication between the people who lived there. That is the origin of the similarities in the music of different countries – and different languages – but which are all part of the formerly Ottoman Balkans.

This is the thesis of musicologists like Eno Koço from Leeds University who explain the phenomena of common elements, like those shown in the documentary”Whose is this song?” (“Čija je ovo pesma”), with the Ottoman influx and urban Turkish musical styles, and the mutual communication between peoples and cultures, having Istanbul as their point of reference.

“Balkan people went to Turkey where they were constantly in contact with the urban music of Istanbul. When they got home they reproduced the songs following the style of the Turkish music,” states the musicologist. The songs, which enliven the discussions in the documentary just mentioned on the great dilemma – “who stole the music from whom?”, are a result of such cultural reproduction. “But it is not necessarily the same song,” specifies Koço, “often there can be similar tunes and different songs circulating in several countries. As in this case considered by the Bulgarian film director, Adela Peeva.”

The Ottoman Empire was not limited to just the Balkans and European Turkey, but also included the Middle East, an area equally open to exchanges and encounters. And Balkan rhythms often recall those of the Middle East. “However this is not only linked to a common membership of the Ottoman Empire,” claims Markelian Kapidani, a musician who, in his music, mixes and elaborates on traditional rhythms. “The symbiosis between the Balkans and the Middle East precedes the Ottoman Empire and seems to have its origins in the time of Alexander the Great, since this part of the world has always been a crossroads, an open space.”

Carsijas of Joy and Pain

Many traditional songs tell of girls who go out in the čaršija, of immense çarshijas, of apples in the çarshijas, of warriors meeting in the čaršija, of trousseau to buy in the çarshija, but also of assassins and drunks who, with their crimes and break-ins remain forever in the memory of the čaršija.

Joyful, rhythmic songs like the Albanian aheng, with simple, comic lines, poking fun at social and family relationships in the town. Perhaps romantic love songs with a range of stylistic symbols with an erotic significance: the women become slim cypress trees, with faces as pale as the moon, and the men powerful as hawks or romantic like song birds with beautiful voices.

But there are also love songs of great suffering which put the essence of the Balkan spirit into words – the fatalism and strong spirituality, recounting events that really happened and inspired singers and musicians.

From sevdah, a Turkish word of Arab origin (from which the Portuguese saudade may have originated), came, for example, the sevdalinke of the Bosnian çarshijas which embody the synthesis of urban elegance and Ottoman artistic sensitivity. These songs are intimate and discreet, but difficult to “export” because of linguistic barriers: it is as important to listen to the words of the stories as to their melodies and rhythms.

An anthology of sevdalinke could reveal as much material of anthropological interest as a history book on Ottoman and post-Ottoman history. A grass roots text without ideology. The stories told in the sevdalinke, sometimes clear, sometimes mysterious, have often inspired writers and artists, including Miljenko Jergović, one of the greatest contemporary Balkan authors who, in one of his most interesting works, reconstructed the stories which synthesize some of Sarajevo’s most beautiful sevdalinke.

In some Bazaars over the centuries songs of a truly Turkish nature have been sung. This is the case of the Macedonian čalgija and the urban music of Scutari and Valona in Albania. Then there are also songs without words. Often they are laments, like the kaba, music expressing loss and profound grief, played on a clarinet or violin. They were created, it is said, by a famous Rom clarinettist somewhere in southern Albania when, suffering from the loss of his wife, he could no longer find tears or words to express his grief for her, but did so with the heart-rending sound of his clarinet.

Music was indeed an integral part of the čaršija, flowing out from kafane and squares. This was where one arranged with musicians for them to come to weddings, christenings and circumcision ceremonies. These musicians were almost always Rom. Much of what is common in music across the Balkans is actually owed to them and their mobility. In some countries it is said of the Rom that they are born with a violin in their hand. Even now the best performers of Balkan urban music belong to this minority group who, despite this fact, are ill-treated.

Evolution

Musicologists do not agree about when Ottoman urban music began. The songs of the present cultural heritage originated in the last century of the Ottoman Empire but probably result from lengthy elaboration and transformation, taking place over generations. They could also synthesize both Ottoman and pre-Ottoman elements. Other influences, particularly in the early 1900s, were Western which even led to the composition of Ottoman opera which was very popular in some Albanian towns.

Later on in the 20th century this type of traditional music was treated with special respect even by the socialist regimes, for the sake of conserving national culture and popular heritage. These genres certainly survived, being part of the urban identity. What will happen to them now is difficult to predict. Fewer performers remain even if there is no shortage of young people to reinterpret this tradition. But the regional market seems no longer interested, prefering music for mass consumption like turbofolk.

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Bazaar Rhythms

Cultural and ethnic crossroads and meeting place par excellence, the çarshija is also the place for finding some of the deepest roots of the Balkan musical heritage. Our inquiry

Fast rhythms and harmonies that make even those who know absolutely nothing about traditional dancing dance. But the melodies can also be slow, mournful or sentimental. The Balkan musical legacy goes well beyond the label which world music has given it: it is not just this exotic version, but a result of the cultural and ethnic crossroads which the Balkans have been for centuries.

Elements from Eastern Europe, Turkish and Middle Eastern rhythms, with here and there a touch of Western music, have all been woven together in an organic way and much of that heritage was synthesized in that special meeting place, the čaršija or traditional Bazaar.

Not only Ottomans

What distinguishes the Balkans musically from the rest of Europe is precisely the coexistence of many elements of a different nature and an enormous variety of rhythms: an Oriental flavour which makes us think of the Ottoman Empire, for centuries an open area without internal barriers and characterized by continuous migration and communication between the people who lived there. That is the origin of the similarities in the music of different countries – and different languages – but which are all part of the formerly Ottoman Balkans.

This is the thesis of musicologists like Eno Koço from Leeds University who explain the phenomena of common elements, like those shown in the documentary”Whose is this song?” (“Čija je ovo pesma”), with the Ottoman influx and urban Turkish musical styles, and the mutual communication between peoples and cultures, having Istanbul as their point of reference.

“Balkan people went to Turkey where they were constantly in contact with the urban music of Istanbul. When they got home they reproduced the songs following the style of the Turkish music,” states the musicologist. The songs, which enliven the discussions in the documentary just mentioned on the great dilemma – “who stole the music from whom?”, are a result of such cultural reproduction. “But it is not necessarily the same song,” specifies Koço, “often there can be similar tunes and different songs circulating in several countries. As in this case considered by the Bulgarian film director, Adela Peeva.”

The Ottoman Empire was not limited to just the Balkans and European Turkey, but also included the Middle East, an area equally open to exchanges and encounters. And Balkan rhythms often recall those of the Middle East. “However this is not only linked to a common membership of the Ottoman Empire,” claims Markelian Kapidani, a musician who, in his music, mixes and elaborates on traditional rhythms. “The symbiosis between the Balkans and the Middle East precedes the Ottoman Empire and seems to have its origins in the time of Alexander the Great, since this part of the world has always been a crossroads, an open space.”

Carsijas of Joy and Pain

Many traditional songs tell of girls who go out in the čaršija, of immense çarshijas, of apples in the çarshijas, of warriors meeting in the čaršija, of trousseau to buy in the çarshija, but also of assassins and drunks who, with their crimes and break-ins remain forever in the memory of the čaršija.

Joyful, rhythmic songs like the Albanian aheng, with simple, comic lines, poking fun at social and family relationships in the town. Perhaps romantic love songs with a range of stylistic symbols with an erotic significance: the women become slim cypress trees, with faces as pale as the moon, and the men powerful as hawks or romantic like song birds with beautiful voices.

But there are also love songs of great suffering which put the essence of the Balkan spirit into words – the fatalism and strong spirituality, recounting events that really happened and inspired singers and musicians.

From sevdah, a Turkish word of Arab origin (from which the Portuguese saudade may have originated), came, for example, the sevdalinke of the Bosnian çarshijas which embody the synthesis of urban elegance and Ottoman artistic sensitivity. These songs are intimate and discreet, but difficult to “export” because of linguistic barriers: it is as important to listen to the words of the stories as to their melodies and rhythms.

An anthology of sevdalinke could reveal as much material of anthropological interest as a history book on Ottoman and post-Ottoman history. A grass roots text without ideology. The stories told in the sevdalinke, sometimes clear, sometimes mysterious, have often inspired writers and artists, including Miljenko Jergović, one of the greatest contemporary Balkan authors who, in one of his most interesting works, reconstructed the stories which synthesize some of Sarajevo’s most beautiful sevdalinke.

In some Bazaars over the centuries songs of a truly Turkish nature have been sung. This is the case of the Macedonian čalgija and the urban music of Scutari and Valona in Albania. Then there are also songs without words. Often they are laments, like the kaba, music expressing loss and profound grief, played on a clarinet or violin. They were created, it is said, by a famous Rom clarinettist somewhere in southern Albania when, suffering from the loss of his wife, he could no longer find tears or words to express his grief for her, but did so with the heart-rending sound of his clarinet.

Music was indeed an integral part of the čaršija, flowing out from kafane and squares. This was where one arranged with musicians for them to come to weddings, christenings and circumcision ceremonies. These musicians were almost always Rom. Much of what is common in music across the Balkans is actually owed to them and their mobility. In some countries it is said of the Rom that they are born with a violin in their hand. Even now the best performers of Balkan urban music belong to this minority group who, despite this fact, are ill-treated.

Evolution

Musicologists do not agree about when Ottoman urban music began. The songs of the present cultural heritage originated in the last century of the Ottoman Empire but probably result from lengthy elaboration and transformation, taking place over generations. They could also synthesize both Ottoman and pre-Ottoman elements. Other influences, particularly in the early 1900s, were Western which even led to the composition of Ottoman opera which was very popular in some Albanian towns.

Later on in the 20th century this type of traditional music was treated with special respect even by the socialist regimes, for the sake of conserving national culture and popular heritage. These genres certainly survived, being part of the urban identity. What will happen to them now is difficult to predict. Fewer performers remain even if there is no shortage of young people to reinterpret this tradition. But the regional market seems no longer interested, prefering music for mass consumption like turbofolk.