Photo: © Andrej Antic/Shutterstock

EU investments aim to support the green transition of the Western Balkan countries, but criticism about the project types and the process remains

As the European Union’s enlargement to the Western Balkans is finally back on the table, aligning legislation with EU law has become a pressing necessity for the candidate countries in the region. This includes adhering to the EU Climate Law, which commits member states to achieving full decarbonisation by 2050. However, achieving significant emission reductions in the Western Balkans remain a formidable task. In 2020, some hope emerged with the EU-backed introduction of the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, a plan that mirrors the ambitious European Green Deal.

Embedded within this vision is the Economic and Investment Plan (EIP), a strategic framework that promises substantial EU investments in the region of up to €9 billion from 2021 to 2027. These much-needed funds are vital in facilitating the region's green transition and fostering greater integration into the EU.

First Steps Have Been Made

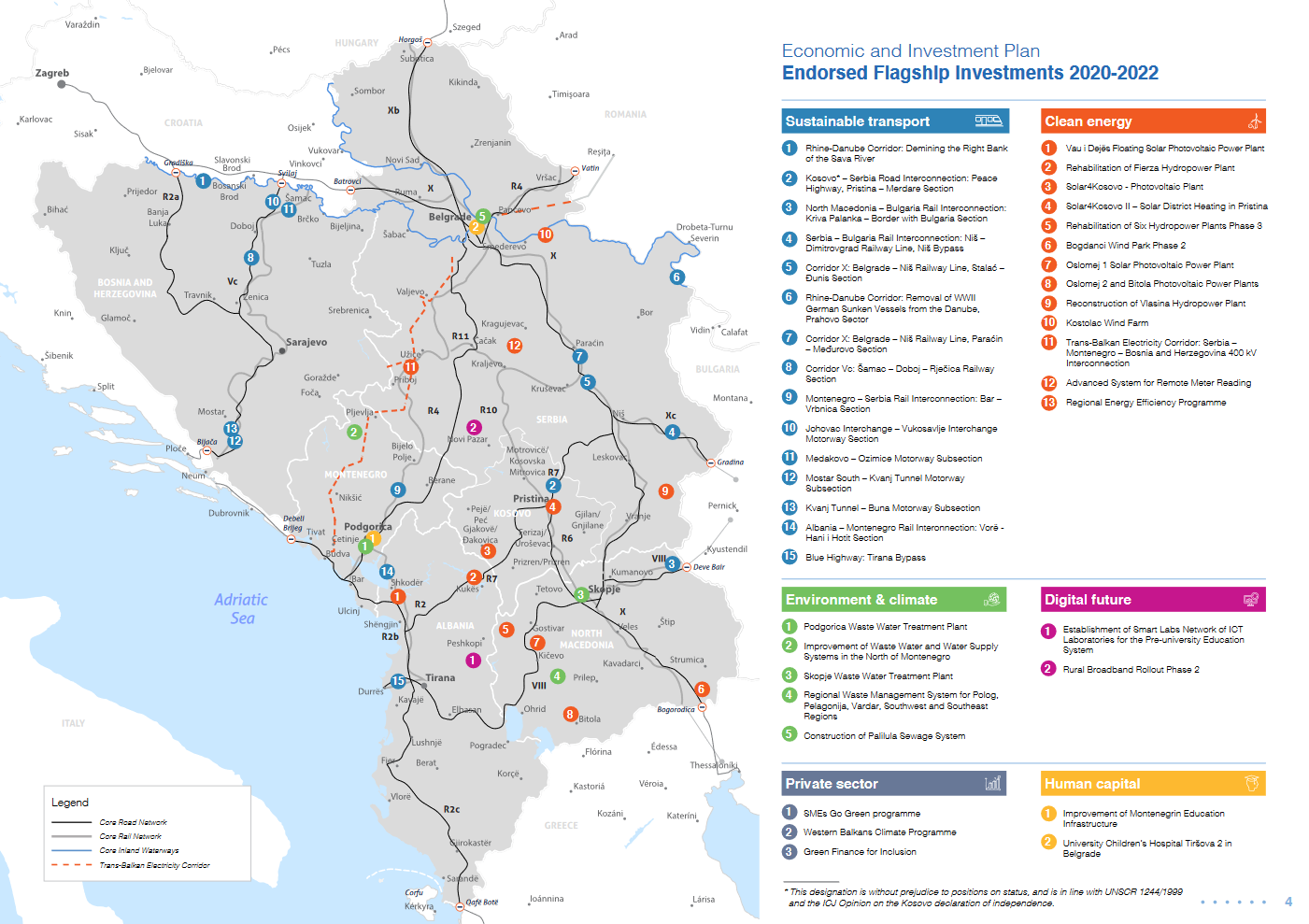

Since the adoption of the EIP in October 2020, the EU approved €1.8 billion in investments in the Western Balkans, so a fifth of the promised funds overall; these investments are expected to mobilise a total of €5.6 billion. Such investments are much needed. “While clearly the Western Balkans have the same finish line on climate neutrality as the EU, the starting line unfortunately differs,” says Selma Ahatovic-Lihic, Senior Communications Officer at the Regional Cooperation Council. The investments focus on 40 flagship projects, most of which are in the areas of sustainable transport and clean energy. They range from new road constructions to Solar projects and the rehabilitation of a hydropower plant. While the projects are spread mostly evenly throughout the region, some differences stand out. For instance, investments in Bosnia and Herzegovina only include sustainable transport projects.

Endorsed Flagship investments 2020-2022 under the EIP. Source: WBIF .

The amount of funding shows that the emphasis is mainly on transportation. Most money goes into sustainable transport, of which similar amounts are invested into railroads and roads. The disparity in investments is striking, with the funding allocated to roads surpassing that of clean energy by more than double.

Roads instead of Railroads

While the Economic and Investment Plan includes various projects intended to support sustainable transportation, renewable energy, digitalisation, and private sector growth, it remains questionable whether all these investments really support the overarching goals of the Green Agenda.

One area of contention is the emphasis on road construction as part of the so-called sustainable transportation projects. Samir Lemeš, activist of the Bosnian NGO Eko Forum, points out that “billions of euros were invested into highways, while there were almost no investments into railways.” Railways and waterways would be more sustainable transportation modes, while increased road traffic will exacerbate emissions. Although these new roads may enhance regional connectivity, the same goal could have been achieved through railways, which emit fewer greenhouse gasses. Moreover, the construction of new roads does not address the primary barrier to connectivity in the region—border control and the associated long waiting times, as a study for the EU Parliament finds.

Coal Phase-Out, But How?

A substantial amount of the EU investments also focuses on increasing energy efficiency. This is a good step to reduce emissions and air pollution, as buildings are significant contributors to emissions, particularly those with inefficient heating systems.

In order to achieve significant emission reductions, the energy sources for heating have to shift towards renewable alternatives to coal and wood. While some EIP projects focus on expanding renewables indeed, an OECD report highlights the untapped potential for solar and wind energy in the Western Balkans. The current investment plan fails to fully utilise these resources, opting instead for controversial hydropower projects with negative environmental impacts. Stanislav Vučković, activist from the Serbian NGO Eco Straža, recognises that “hydropower is one of the solutions for a source of renewable energy,” but simultaneously warns that “care must be taken to minimise the damage to ecosystems and the environment.”

The high costs of transitioning whole economies away from coal, including the socio-economic consequences of a phase-out, raise concerns that governments might hesitate to move forward with it. Selma Ahatovic-Lihic worries that “climate change is becoming more and more expensive, representing an additional burden for the weak economies of the Western Balkans region, where energy poverty is a major issue. Western Balkan economies cannot afford a new and costly ‘green assault’ on their economies.” Therefore, EU investments in this area become crucial to encourage and support the shift toward renewables. So far, the amount of funding is limited however.

The current allocation of funds also falls short in addressing climate change and environmental damage comprehensively. While a few projects focus on waste and wastewater management, there is a notable neglect of other vital environmental issues. Areas such as sustainable agriculture – despite its significant impact on the region's exports and employment – currently remain excluded from the investment plan.

Good Governance Needed

As the EIP projects are still in their nascent stage, it is not possible to assess their impact precisely. What is already clear is that their success hinges upon the institutional environment and capacity building. Weak institutions and the privileges bestowed upon state-owned enterprises pose significant challenges to effective investments in this sector. Moreover, deficiencies in the education system and depopulation must be addressed to foster a skilled workforce capable of driving economic development. “We lack not only the funding but also the necessary infrastructure to support project implementation,” states Stanislav Vučković. “We need opportunities to have direct experience and exchange with the EU countries.” According to the activist, “the main obstacle to the genuine green transition of Serbia is the Serbian regime supported by the EU.”Vučković, activist from Eco Straža

Western Balkan municipalities must develop the necessary capacities. Conducting comprehensive environmental impact analyses is crucial to guarantee that projects do align with the green transition. However, their effectiveness ultimately relies on the implementation phase, making good governance practices indispensable.

NGOs also raise concerns about the lack of consultation with civil society during the planning process, highlighting a need for greater inclusion and transparency. Samir Lemeš criticizes that “the process is not transparent, there is not enough information available publicly, and most of the funds are being used by consultants from the EU.”

Putting Numbers Into Perspective

Overall, the amount of funding allocated to the Western Balkans through the EIP is comparatively small when compared to the EU funds flowing into neighboring countries like Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, and Greece. Indeed, member states benefit from many more programmes and opportunities for funding – hence the candidate countries’ interest in finally accessing the EU. According to Selma Ahatovic-Lihic, “the convergence gap between the Western Balkans and the EU still remains huge.”

The intersection of geopolitics adds another layer of complexity. The financial support provided by the EU through the EIP is part of the existing IPA III funding, which is specifically earmarked to aid countries in their journey towards EU accession. As a result, these investments are subject to conditionality, meaning that the amount of funding received is contingent upon the performance of each individual country.

On the other hand, for the EU to make a credible commitment to the Western Balkans, it also needs a clear perspective. “The date of Serbian accession to the EU has now been postponed indefinitely, for decades for sure,” says Vučković. “Hence, any financial support by the EU institutions is regarded - to make an understatement - with a grain of salt.”

While 8 out of the 9 billion Euros are grants, which implies that they don’t have to be paid back, 1 billion Euros are guarantees through the Western Balkans Guarantee facility. A guarantee means that the EU does not directly lend money, but guarantees that the debt will be repaid (at least partly) should the lender default. The EU expects to mobilise 20 billion Euros of investments over the next decade through its investments and grants in the region.

This content is published in the context of the "Work4Future" project co-financed by the European Union (EU). The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project. The responsibility for the contents lies solely with OBC Transeuropa. Go to the "Work4Future"