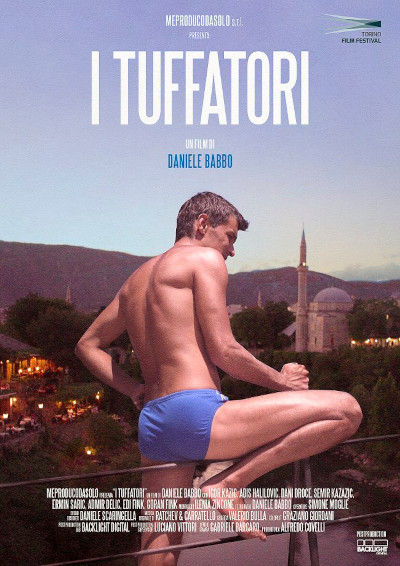

A screenshot from the film "I tuffatori" by Daniele Babbo

Starting from those moments of precipitous flight towards the Neretva, the first long feature directed by Daniele Babbo shows both the love for a city and how hard it is to live in it. An interview

Daniele Babbo (also known as Dandaddy for his videoclips ) presented at the Turin Film Festival 2020 his first documentary about an icon of the Balkans – the divers of Mostar, figures inextricably linked to the Stari Most bridge, rebuilt after the devastation of war. A choral portrait which looks under the surface, approaching its subjects with sensitivity and respect. Babbo answered our questions on the phone, starting like this: "I have always been a fan of the Balkans... I always go east. Uzbekistan, Georgia, Romania are the last destinations I visited. I am fascinated by the east".

"I tuffatori" is your first work: you say you met them during a holiday, but how did your first meeting go?

It went like this: I was on vacation, I was doing a tour of Bosnia, and after Banja Luka and Travnik I arrived in Mostar. One of the first scenes I saw was this guy looking down from the bridge – the same scene you see in the preview. While I was watching him, I heard a man speak in Italian and I approached him to ask for some information. I already knew the history of the bridge and was vaguely aware of the tradition of diving, but not much. Over coffee and a cigarette I made friends with Mustafa, who then became a very important figure throughout the documentary-making process.

Mustafa is a man of about sixty, who lived in Italy for twenty years after the war and then returned to Mostar. He helped me approach the divers. That day it was just a quick meeting, but I was left with curiosity: tourists came and photographed them and then left. Instead, after the dive they went back to the club above the bridge, sat down, and talked and talked... I asked Mustafa what they were talking about, and he replied that they were talking about technique, what it was like before the war... the same which happens in the film and still today. They are always extremely attentive to what they do, they are passionate, and put their heart into what they do.

When did you understand (or decide) that it would become a film?

In my head the curiosity was born to find out about these people – what they are like, besides brave enough to jump off a bridge of 20 plus metres into an icy river. After a few months I returned and asked Mustafa if I could join them and stay with them for a while. I stayed 3-4 days and they were very warm and nice to me. They said to me, in full Balkan style: “Don't worry, you can stay here with us, there's no problem”. But slowly I wanted to let them understand that I didn't want to just tell about the dive, but to be with them, and it took me a little longer.

How did you approach them? Was it difficult to and access their community?

It was, also because language was a barrier: I don't speak Bosnian, so I spoke English with some, and coffee and cigarettes with others. In July 2017 I went back alone and stayed with them for a whole month. That was an important step, 24/7 living together – they would say "You're a brother from a different mother", and it always made me laugh.

I ate ćevapi with pita all day, I drank a thousand beers and rakija. If I didn't drink it would have been harder to make this documentary, but being from Friuli I had a good start. They immediately welcomed me and slowly I began to make friends with them and they started to tell me more and more. I got especially close to some of them – Igor, Miro, and Goran.

The film first shows the divers at work and examines their different techniques and personalities. Then you get closer, especially to two of them. How did you manage to get so close?

Because there was a lot of respect: I never asked them to act something for the camera, and they never told me not to do something. It was all very gradual and therefore it was almost normal for them to come back to the club and hang up their swimsuit while I came in to change batteries: my presence was almost part of their routine. There wasn't a single day when I didn't stay with them at the end of the day to chat, eat, have a beer. It was like when you go on a trip with close friends.

You even followed Igor him to Norway...

Shortly after becoming a father, Igor told me that he had found the opportunity to go to Norway and that he had accepted, since there is very little work in Mostar in winter. So I joined him. He had to leave everything he loved, his bridge, his land. He was also the best diver of all and what struck me a lot were these phone calls with Gouma and his little son. Besides, he constantly listened to his country's music, that he loves. One evening it was very cold and he played this song by Dino Merlin, Mostarska, and I could see it was really destroyed. He wanted to go home. This is love for Mostar, in my opinion.

Is there something you would like to have included in the film but hasn't found a place?

So many things were left out! At a certain point I had to reflect and understand what the best way was to get what I wanted, that is to show a community of young men who have gone through and are going through difficult times, who do not know what the future will be like, and yet have the bridge tattooed on their chest. They are brothers and they treat you as such. I wanted to show this, with no explanations or compromises or talk of the war. I wanted only Miro and Goran to talk about the war, because they experienced it and therefore it was right that they did.

Is that why you used archive footage?

My first thought is that not everyone knows that world. You can get attached to the characters regardless of their place of origin or otherwise, but in this case the context is important for their story. When Goran told me the bridge was destroyed just as they were in the concentration camp, so, I thought I could show it. I considered the use of the archive important, because it was right to show the suffering that Goran was telling me about.

I also used the clip where young Goran dives, because he remembers that they did it even before the war, to show that they do out something that has always been there and to show Mostar before the war. All of them are very nostalgic for Tito's socialist period. Today, many of them don't dive anymore: Igor is in Holland, Edi has become a father and lives in Germany with his partner...

What is your idea of Mostar (and Bosnia and Herzegovina) today?

My idea of Mostar is complex. Everything that happened still impacts a lot on those areas. A war ended in Mostar and since then everything has changed radically: not only the bridge has been rebuilt, a city has been rebuilt. Mostar today is a small jem for tourism. Diving is part of this and the divers live thanks to that every day, like the souvenir shops and trinkets survive thanks to tourism. There is no work, at least not as much as before, even menial jobs are scarce. Unemployment is very high. It's all about tourism and when I was there off-season, like in February-March, the city dies.

This happens throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina, even in Sarajevo it is the same thing, although things are different and work differently. I see that people are kind of broken inside – they see their future there is impossible. Do you want to work? You know that to do this you have to leave Mostar. But the bond with that city is huge, and therefore there is always this laceration, this clash between the strong sense of belonging and the need to survive.

In Mostar people finally voted after 12 years. One thing I would like to add is about the division between the Bosniak side and the Croatian side; they look like two different cities. The divers were almost all born of mixed marriages, which was always a normal thing before the war. They were just born in a different world. Goran says it in the film: no one cared whether you were Serbian, Croatian, or Muslim. With all the limits of Tito's socialism, Mostar used to be a kind of paradise. People could work, earn a salary, and had time to drink coffee and smoke cigarettes. Now it's difficult, despite the propensity to stay together. This situation is the result of well-studied work by those who wanted to divide instead of unite – a process that has lasted for 40 years and still goes on. Nationalisms do this and it is inevitable that these divisions are felt.

Elezioni

Twelve years had passed since the last administrative elections in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Then, citizens finally returned to the polls on Sunday, 20 December. Among the 100,864 people entitled to vote in Mostar, many voted for the first time to elect the government of their city. These are not very young people, but people who are already about thirty years old. In fact, it took the two main ethnonational parties – Bakir Izetbgović's Bosniak SDA and Dragan Čović's Croatian HDZ BiH – twelve years to reach an agreement after the impasse of 2010. To learn more

To Top

To Top