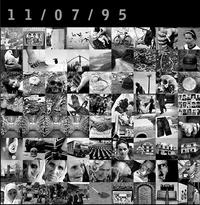

The memorial gallery 11/07/95 (photo by Marzia Bona)

In Sarajevo, a new space dedicated to the memory of Srebrenica lives on Turkish funds, with little support from local institutions. Art, memory, and cooperation in an interview with Ivica Pandžić, spokesperson for the association that manages the memorial gallery

The '07/11/95' memorial gallery in down-town Sarajevo was inaugurated on July 12th. The name of the space refers to the date the forces of General Mladić entered the Srebrenica safe area and started a massacre of civilians that lasted for days – the first genocide in Europe after the Second World War.

The gallery houses the first permanent exhibition on the Srebrenica genocide and is the result of documentary work that lasted seven years. With an area of 300 square meters and cutting-edge infrastructure, the gallery was sponsored by the Turkish Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA) and is managed by the association Sjećanja Kultura (Culture of Remembrance).

According to the project spokesperson Ivica Pandžić, the exhibition's goal is to 'preserve the memory of Srebrenica's suffering'. The exhibition features original photographs by Tarik Samarah, former collaborator of Sejla Kamerić and Swanee Hunt, as well as video documentation and a text edited by Emir Suljagić, former Minister of Culture of the Sarajevo Canton.

A form of memory, however, somewhat weakened by the fact that support for the project comes almost exclusively from the Turkish Development Agency. Once again, local institutions are not showing real commitment, not even in the form of patronage. Once the lights go off after the ceremony in Potočari, Srebrenica is forgotten until the next good opportunity to be in the news headlines. Milan Kundera's words come to mind: 'the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting'.

An interview with Ivica Pandžić, spokesperson of the association managing the gallery.

Your association is called "Culture of Memory". Can you tell me more about what this concept means in Bosnia today?

The name of the association refers to the memory of missing persons in Srebrenica. July 11th 1995, the date of the fall of Srebrenica, marks the beginning of the crimes witnessed by this exhibition. We chose to open the doors to the public on July 12th because that is the day in which to start nurturing a culture of memory of the genocide perpetrated in Srebrenica.

Our train of thought is to ward off the trivialisation of evil. In the case of Srebrenica, we are talking about a planned crime, which must be shown and borne witness to. There are names and surnames, it is not a cosmic evil for which no one is guilty. As each name remembers a victim, we must bear in mind that there are names for the perpetrators as well. We are not alone in this, there are many local associations working in Srebrenica, dealing with different issues, related to memory but also to returns, a crucial mechanism to avoid forgetting and oblivion. But when we look at politics, nothing concrete has been done, apart from a few verbal statements.

How was the project born?

The permanent exhibition aims at balancing respect for the victims and their families with the will to show and remember the crime committed. Both are priorities, and photographs have a specific function. Never as in this case can images tell more than a thousand words. Here we have photographs that tell their own story, and any further interpretation, particularly when it comes to political manipulation, would give a misleading reading of this project.

The idea of a permanent memorial gallery was born in 2005, following the publication of a book collecting photos by Tarik Samarah. Given the positive reactions, we decided to create a permanent exhibition of the photos published in the book. It then took seven years before the project came to life, but time passes slowly here, so it was not a problem.

Tarik was the inspiring mind behind the project and the author most of the photographs on display. Right from the beginning we involved people and organisations that could help us preserve the memory of the events from the manipulation of everyday politics. Tarik is also the curator of the exhibition space and manager of temporary shows.

A photographic exhibition already exists in Srebrenica, but it clearly suffers from poor accessibility. For visitors to our country, both tourists and members of the diaspora, it is difficult to get out to Srebrenica to see the documentary and photographic material housed in the memorial in Potočari. We therefore chose Sarajevo as the place that could ensure maximum visibility.

What was the role of the associations involved in the project?

Their role was crucial. The photographic part is itself a work of great intensity and enormous size, which occupies the central part of the exhibition. But it does not end there. There are videos and documents, including a list of all missing persons in Srebrenica – we could have never gathered all this material on our own. The documentation was provided by the Memorial Centre in Srebrenica - Potočari, the Mothers of Srebrenica and Žepa, and the Institute for Missing Persons. Equally important contributions arrived from the Youth Initiative for Human Rights (YIHR), Fama, Cinema for Peace Foundation and the Genocide Video Archive. The skills of each partner have guaranteed a rigorous approach to the facts.

Each document has been verified over and over again, the sources are trustworthy and reliable. It would not be admissible to present approximate information on a topic like this. It took years to collect the materials presented in this exhibition and the contribution of the partners has been essential.

What was the audience's reaction when the space first opened?

Silence. The emotional strength of the exhibition is enhanced by the path the visitors follow. Upon entering, you are immediately faced with the names of the victims, each of them, name and surname name. The intention is to personify each victim, beyond the numbers that, however great, cannot communicate the immensity of the crime nor the intensity of the suffering we are talking about. Silence is an understandable reaction, considering the pain that comes across in this exhibition. The reactions of the press have so far been positive, too. There was no criticism, despite the highly political content of the exhibition – but this does not mean there will not be any.

The opening of the gallery was made possible by support from the Turkish Development Cooperation Agency (TIKA) and a district of the city of Sarajevo (Stari Grad). Have you sought other institutional support and what reactions have you encountered?

We sought support from several institutions, but the answers were scarce. Only TIKA responded constructively and covered the significant cost of the renovation of the exhibition space.

The municipality of Stari Grad with mayor Ibrahim Hadžibajrić (who transitioned earlier this year from the SDA to the Party for a better future, SBB--Ed) gave us the long-term location. An interesting detail is that, once we found the financial support, arranging the spaces and the exhibition only took about two months. For the future, I don't think we will be able to count on the Turkish cooperation again.

We should expect something from local institutions, but much depends on who will occupy political posts after the next election (which will be held in October --Ed). The Gallery will need to be able to support itself.

Looking at cultural policies in the country, does it worry you that support for a project like yours came almost exclusively from a foreign partner?

The behaviour of local politicians is influenced by constant temporariness. This applies in every area, but the volatility of political responsibility is perhaps felt most intensely in the field of culture, which lacks a shared strategy. TIKA has supported honestly and without conditionality. The relationship of mutual respect has made this a partnership rather than a donation. There is a constant commitment by Turkey to themes such as education and culture in Bosnia Herzegovina.

It is interesting to note that for them there is no crisis or recession: Turkey is a stable country with a strong identity and an established sense of culture. Besides its European ambitions, it also demonstrates a strong commitment to relations with the Balkans. Some speak of Neo-Ottomanism, but it makes no sense to me. That is the past for Turkey – now, the Balkans are mostly an economic space, to penetrate also through public diplomacy interventions such as the financing of the “11/09/95” Gallery.

To Top

To Top