Thirty years ago, from February 8th to 19th, the fourteenth edition of the Olympic Winter Games was held in Sarajevo. A few years after the Olympic facilities, a symbol of common history and life, were targeted by the bombings

A metre of snow and twenty degrees below zero would faze no one in Bosnia. You would clean the main roads, dig a path through the snow from the door to the street, and life would go on as usual.

Sometimes it would be snowing even at the beginning of October. We would go to a restaurant for dinner and when leaving, in the small hours, the first snow would be meeting us. Tap-tap, on the tips of the light, elegant shoes, you would try to cross the whitened street without slipping or falling. The snow remained until April, sometimes even longer. It could be snowing even in the summer on the mountains around Sarajevo. Local newspapers carried the news, but no one was surprised.

In the spring, one could be in the woods on the Bjelašnica mountain, south-west of Sarajevo, in a normal climate, everything quiet, and ten minutes later in the middle of a snowstorm. Even those who knew the mountain were sometimes in danger of being lost or remain under the snow, like the eleven talented young skiers who, in the sixties, lost their lives during an unpredictable storm on Mount Bjelašnica.

Is it snowing yet?

In short, snow was never a problem for us. We always had it in abundance. But at the beginning of February 1984, its inexplicable absence tormented us. About four million citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina were scanning the sky waiting for the snow. We woke up in the night to check. The first question in the morning upon awakening was, "Is it snowing yet?". We blamed meteorologists for miscalculating and believers would pray for the snow. All in vain. In any event, cannons to make artificial snow were also ready, but this seemed like an excess of precaution. In the hundred years preceding the XIV Olympic Games, there would always be snow in Sarajevo and the surrounding areas in February.

The day before the Games in Sarajevo, on February 7th, 1984, the weather was spring-ish. Not one snowflake in sight.

I felt like crying, it felt like a real injustice. Many others felt the same.

Everything was ready a year before the Games began. The new Olympic village had been built. New hotels were opened and old ones refurbished. The Baščaršija, the old and ruined Ottoman city, in danger of being destroyed in order to build a "more beautiful and more ancient" one, had been recovered. The main streets of the city had been rebuilt and enlarged, the façades of the buildings painted, the electric tram rails changed, the central station restored. All the structures needed for the winter Olympics were built on the mountains around Sarajevo – Jahorina, Bjelašnica, Igman, and Trebević.

This is how Sarajevo people look like

Every day, several thousand young people from all over Bosnia rehearsed the choreography for the Olympics opening and closing ceremony. The main Japanese newspaper "Yomiuri Shimbun" asked, with a headline all over the front page, "Where did they find all those beautiful girls and tall guys?", and then countered with the subtitle: "This is how Sarajevo people look like". To avoid flu-induced absence, everyone got immunised with powerful vaccines – “those for the horses”, jokes Vanya. She and Svjetlana, two Bosnians who moved to Trieste, had participated in the Games. Today, thirty years later, still beautiful and tall, they reminisce with nostalgia the times of the Olympics.

In the preparation phase, most of us worried about the fog rather than the snow. Fog too was always present in Sarajevo and its surroundings. For the local airport to operate in thick fog, our engineers had prepared the chemicals which could get rid of the fog – just like in an old Bosnian song, “duni vjetre, malo sa Neretve, pa rastjeraj maglu po Mostaru”. Everything was ready, perfect. Thousands of athletes, journalists, and tens of thousands of guests were already in town. The only thing missing was the snow.

I wanted to participate in some way in the event, to be helpful... I would have been happy to shovel the snow, hold a pole, point the way to the toilet, whatever. I applied as a volunteer for various committees, but not one accepted me. There were already thirty thousand people working, half of them were volunteers from all over the former Yugoslavia. Young volunteers organised into work brigades (radne brigade) tended to the Olympics constructions on the mountains. During the Games, four hundred waiters from all over Yugoslavia were in Sarajevo to serve guests.

The centre of the world

The evening before the start of the Games, I thought, I could not stay at home while history was reaching my city. Sarajevo was shining. The streets were crowded. Shops, restaurants and bars were open all night, full of people. Thousands of people strolled, spoke aloud. Those who could not communicate in a foreign language did it in friendly gestures, photos. We laughed for no reason, just because we, the people of Sarajevo, were gathered there, together with the guests, for a big, beautiful, important event. We felt like the centre of the world.

In such an atmosphere it began to snow. I still remember exactly where I was: on Vase Miskina, today Ferhadija street, where the old part of the city, the Baščaršija, begins. There were people jumping with joy. Others held hands and danced, someone screamed. I was laughing uncontrollably, holding my arms open, turning around with my head up. I wanted to feel the snowflakes on my face.

I believe that on that evening many Communist leaders, necessarily atheists, thanked God.

It kept snowing in earnest, all night. The snow was beautiful, dry, the kind that does not dissolve immediately, but stays. The snowflakes were big, stylish as butterflies. At first the snow was falling shyly, then more and more dense. It seemed that someone up there had opened up a bag, and was no longer able to control the speed at which it emptied.

Before, we had been worried because there was no snow. Now, the situation had reversed. In a few hours there was more than a metre of snow. Slopes urgently needed to be levelled. Marc Hodler, President of the International Federation for skiing, worriedly asked Branko Mikulić, presiding officer of the Bosnian Olympic Committee, how he planned to solve the problem.

"You need a thousand people to pave the runways, how can you find them at this hour of night?"

According to witnesses, Branko Mikulić replied: "What do you think, will 5,000 be enough?"

A fairy tale

By radio, citizens were invited to come to the rescue. Thousands responded and worked throughout the night, including the soldiers of the Yugoslav People's Army. The next morning, the slopes were perfect, the whole town clean and tidy. "We were so excited, we would catch snowflakes even before they fell to the ground", recalls thirty years after Meho S., a taxi driver in Sarajevo.

Those were magical moments, like living in a fairy tale. In fact, the XIV Winter Olympic Games in Sarajevo, in 1984, could in many ways be considered a miracle.

In 1977, someone had been laughed at for proposing Sarajevo as host to the Winter Olympics. No one believed it could happen. The Olympic Games were organised by the rich countries of the West. It was, and still is, a very prestigious, expensive event, a showcase and a business card to the international scene. To win, Sarajevo had first to convince skeptics at home. The application had to be approved by the Communist Party and the Government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and approved and supported by the Federal government.

Other republics of Yugoslavia considered Bosnia and Herzegovina a "tamni vilajet" (a dark, retrograde world), a sort of poor cousin who deserved sympathy and help, but nothing more. As a result, the first reaction of the other republics was strong disbelief. Finally, approval was obtained at home. At the international level, Sarajevo found itself competing with Sapporo, Japan, and with the joint application of two Swedish cities, Falun and Göteborg.

After making his last visit to Sarajevo to test its ability to host an international event of this magnitude, Marc Hodler had reported to the Olympic Committee: "Bosnia and Herzegovina is a country that is developing rapidly, people live free and are happy".

Before the vote, British journalist Pet Bedford wrote: "If you choose Sapporo, the Japanese will arrange a plane to visit Tokyo, and if you opt for Falun and Göteborg, Swedes will show you the fjords and icebergs. But if your choice falls on Yugoslavia and Sarajevo, you will find friendly people, a great heart, and beautiful mountains".

The Communist Olympics

The XIV Olympic Winter Games were held in Sarajevo from February 8th to 19th, 1984. It was an event with several unprecedented records. It was the first Winter Olympics to be held in a communist country. It was a record for the number of participants from forty-nine countries, with 1,272 athletes (274 women, 998 men) who competed in thirty-nine disciplines, followed by 7,393 journalists and seen by two billion viewers. The organisers had sold 250,000 tickets and earned a total of $ 47 million. Thanks to the Games, 9,500 new jobs were created.

For the first time, as a demonstration sport, at the Winter Olympics athletes with disabilities competed in the giant slalom, and for the first time in the Olympic history, the pair of figure skaters on ice Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean, England, received the maximum score.

The Winter Olympics in Sarajevo also launched one of the greatest sports icons of the late twentieth century, East German (at the time, East Germany existed as an independent country) figure skater Katarina Witt, who won the gold medal.

For the first time, Yugoslavia won a medal in the Winter Olympics. Slovenian skier Jure Franko won indeed the silver in the giant slalom, leading the entire nation into ecstasy. During the award ceremony, in front of the sports and cultural centre "Skenderija", tens of thousands people shouted: "volimo Jureka, više od bureka" (“We like Jurek more than the burek”, the favourite national dish).

"Those were different times, and the values were different. We were promised a VCR in case we won. And I thought: if I run well in the second round, I'll bring home a VCR", recalls Jure Franko.

Juan Antonio Samaranch stepped in at the Olympics in Sarajevo for the first time as President of the International Olympic Committee. In his speech at the closing of the Games, he said that "the Olympic movement has been enriched. For the first time the Olympic Games were organized by an entire people". That time a friendship was born between the city and the dignitary, one that lasted for twenty years, until Samaranch's death.

The end of the story

In the early months of the war, in 1992, many Olympic buildings were destroyed, targeted on purpose, like everything that documented the common history and life of Bosnian and Herzegovinian citizens. The Zetra sports centre, with the magnificent hall of ice, which had been the stage of the closing ceremony of the Olympic Games, was bombed and set on fire, destroyed to its foundations. The Skenderija centre, the Olympic Museum, the hotels in the mountains... All destroyed.

Already in April 1992, on Jahorina mountain, the Serbs were stationed with Kalashnikovs at the start of the ski lift, to charge for the ticket. Mount Trebević, so close we considered it the mountain of our backyard, was no longer the same for the people of Sarajevo. After the war, many never returned there. The bob-sleigh slopes were mined during the war. Today they are abandoned, only a few brave venture there to collect old bullets and sell them to the craftsmen for making souvenirs.

The Olympic Villages, Mojmilo and Dobrinja, were designed to become the new districts of the city. It is a wide, beautiful area, close to the airport, where, after the games, 2,750 modern apartments were distributed to those who did not have one.

At the beginning of the war, in April 1992, the district of Dobrinja was heavily bombed. The Serbs tried to occupy it, in vain. It remained under siege for the duration of the war, isolated from the rest of Sarajevo, a sort of siege in the siege. The struggle of the inhabitants, mixed people of all ethnicities and religions, is a story of exemplary courage and strength. Today, Dobrinja is crossed by the invisible line of divided Sarajevo.

In 1994, the XVII Winter Games were held in Lillehammer, Norway. Samaranch interrupted his stay there and returned to Sarajevo, to show his solidarity with the city and its citizens. With his arrival in besieged Sarajevo, Samaranch showed the courage and determination that many politicians lacked at the time.

"With an air of defiance, as if there were no danger from the hills, but visibly shaken, Samaranch was standing on the ruins of the sports centre Zetra where, ten years before, he had declared the Winter Olympics closed. For us it was the sign that we were not dead, that we had not been abandoned or forgotten. We were so grateful... People came to see him, to touch him", recalls Edo Numankadić, director of the Olympic Museum in Sarajevo.

Samaranch promised that he would do everything possible to reconstruct the Olympic Centre Zetra. He kept his promise and, in 1999, the centre was rebuilt and opened.

Thirty years later

These days, Sarajevo is preparing the celebrations for the thirty anniversary of the Winter Olympics (1984-2014). The celebrations are organised also in other countries in the world, where over a million Bosnians spread after the war. In Melbourne, Australia, organisers invite fellow country-people "to relive the Winter Games, to be together and revive, for a moment, the flame within us".

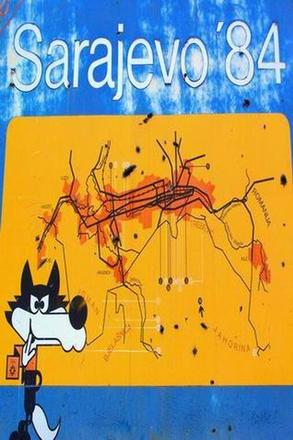

Thirty years later, the symbols of the Olympics are still present in Sarajevo. The mascot "Vučko" (the pet wolf) is now the biggest selling souvenir for tourists, and its faded image can still be seen on the façades of several buildings. Road signs point to "the Olympic mountain", people like to talk about it and many, sighing, remember the times when "we were happy and united".

But today the Serbs ski on mount Jahorina, the Bosnians on Bjelašnica.