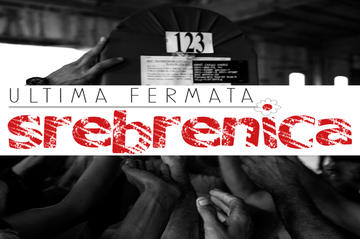

Srebrenica, Potočari © photo Andrea Rizza Goldstein

Almost thirty years after the genocide we are very far from starting a dialogue and a public discussion – in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Europe – on the memory of what happened in Srebrenica. An interview with Andrea Rizza Goldstein

(This article was published in collaboration with Meridiano 13 )

Andrea Rizza Goldstein, photojournalist, worked from 2010 to 2017 with the Alexander Langer Stiftung Foundation for the Adopt Srebrenica project, a psycho-social project on the Bosnian post-conflict phase. Since 2017 he has been working for Arci Bolzano-Bozen as coordinator and member of numerous projects including “Last stop Srebrenica ”. A member of the National Arci Memory and Anti-Fascism Commission, he collaborates with many high schools in the Province of Bolzano as an external consultant for training in citizenship projects on the themes of memory, human rights, anti-discrimination, and conflict management. We interviewed him on the occasion of the 22nd anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide.

On 11 July 1995, Bosnian Serb troops led by General Ratko Mladic entered the "protected area" (by the United Nations) of Srebrenica. In the days following the fall of the city, Bosnian Serb military and paramilitary forces systematically killed over 8,000 Bosniaks – Bosnian Muslims. It was the first genocide in Europe since the end of the Second World War, acknowledged as such by many international criminal justice sentences. How was the event received in Europe and what has its legacy been in recent European history?

Since the start of the Bosnian Serb final operation on Srebrenica, the area had been monitored by US spy planes and there are aerial photographs documenting the deportations of Bosnian men to the places of execution. On 14 July 1995, the United Nations Security Council issued a statement based on information relating to "killings of defenceless civilians" in Srebrenica, condemning them as "unacceptable ethnic cleansing". There are also official requests for international intervention, addressed to the entire UN-UNPROFOR chain of command by the Bosnian-Muslim leadership, regarding the fate of several thousand Bosniak prisoners held at the Nova Kasaba sports field, who will then be killed in the following days. I mean that, on the UN-UNPROFOR-Contact Group line, it seems quite clear that there was an awareness of what was happening in the Srebrenica area. I am not aware that there were international interventions to prevent this from happening. And the mass killings continued until 16-17 July, while liquidations of smaller groups of prisoners were recorded until late July.

The problem is that for a variety of reasons Srebrenica's fate was probably already sealed. From the documents available, including the Directives of the UNPROFOR Command, it is clear that in the button rooms it had already been decided not to intervene.

The issue of international responsibility in the Srebrenica genocide, as the culmination of the tragic violent dissolution of the former Yugoslavia, has found very little space in the European public narrative. These responsibilities start from having accepted to speak, legitimising them, with local political leaders who promoted ethno-national exclusivism projects as a solution to the Yugoslav political-institutional crisis. The vicious circle initiated by international mediation in supporting "strong men", "stabilisers" is at the basis of the escalation of violence that has produced ethnic cleansing – a term coined precisely to describe what was happening in the former Yugoslavia – ethnic mass rape as an instrument of war, deportations, concentration camps, and a new genocide in Europe.

Still, the speeches and statements of local politicians were quite clear. At the international level, however, we just wanted to steer clear of anything that smelled like Yugoslavism, like socialism, in the context of Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. And what the local propaganda produced and the communities of the dissolving Yugoslav federation voted for were ethno-nationalist political parties and leaders, champions of ethno-territorial group interests. Karadzic himself, political leader of the Bosnian Serbs – sentenced to life in prison in 2019 for the Srebrenica genocide and other crimes against humanity, including the siege of Sarajevo – declared in November 1991: "This is a struggle until the end, a struggle for living space”. The international community, Europe, pretended not to understand that he was talking about Lebensraum.

To understand what place the Yugoslav dissolution, the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Srebrenica genocide have in the European public narrative, just look at school manuals. Here in Italy, for example, the Yugoslav wars of the nineties are dealt with in a skimpy chapter that often refers to a civil war – which it was not! – or to an ethno-religious conflict and finds its cause in the concept of "Balkan powder keg" or in the alleged anthropological-genetic predisposition of those peoples to violence. These are convenient explanations to gloss over the issue of international responsibility in the violent dissolution of the Yugoslav federation, up to the Srebrenica genocide.

If it is true – and I think it is – that "the construction of public memory is a process in constant transformation, where memory is the result of a process of choices and selection, of public conflicts and first of all the relationship between memory and oblivion, between what a community wants to remember (and celebrate) and what it wants to forget, remove or hide" [Bruno Maida, "Making memory today", Ed. Arci, National Seminar on memory and antifascism, Collegno (TO ), 27-28 June 2015], the omission of memory (and analysis) of what happened in the former Yugoslavia, up to the Srebrenica genocide, is fully part of this process of selection and oblivion. With the clear objective of glossing over international responsibilities, while in fact it would have been fundamental – after Srebrenica – to stop and reflect on the system crash and all related responsibilities.

Besides death and destruction, what were the consequences of the genocide for the population of Srebrenica and for the ethnic balance?

I try not to use the term "ethnic" when referring to Bosniaks, Serbs or Bosnian Serbs, Croats or Croat-Bosnians, etc. I prefer using ethno-national (group, belonging), even though they were defined as peoples in the Yugoslav political language. Some had the juridical-constitutional status of constituent peoples – Slovenes, Croats, Muslims (Bosniaks since 1992), Serbs, Montenegrins, and Macedonians – and were written with a capital letter. Then there were the nationalities (national minorities) such as Hungarians, Germans, Italians, Slovaks, Albanians, etc. and the Roma, because Yugoslavia – the only country in the world – constitutionally recognised the status of national minority for Roma. And there was no difference, in the definition, for example between Serbs from Serbia or Serbs from Croatia or Serbs from Bosnia; a Serb was "Serbian", if at the census they declared themselves as such, understood precisely as belonging to one of the six constituent peoples, regardless of whether they lived in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, or Slovenia. At the census one could also declare oneself a Yugoslav, which in fact was the status of national citizenship.

These "complexities", these legal institutions outside the box of Western structures, have been reduced to the (exclusionary) identification with an ethno-national group and we can safely say that it was nation-building a century and a half late, with the actualisation of Blut und Boden as a (criminal) ideology mixed with the concept of Lebensraum, which has shifted the ethical and moral meaning of everything that has been committed in the name of the "nation", right up to the genocide. Nicole Janigro explains very well this "explosion of nations" with respect to the failure of the attempt to weaken national micro-identities in favour of a Yugoslav meta-identity and the possible repercussions on European meta-identity, in the passage on "The Europe that dies in Sarajevo is that of Western Reason”.

Another element to take into consideration, if we talk about the consequences of genocide, is trauma. Before the war (1991 census), the municipality of Srebrenica had 36,666 inhabitants including 27,572 (75.19%) Muslims, since 1992 called Bosniaks; 8,315 (22.67%) Serbs; 380 (1.03%) Yugoslavs; 361 (0.98%) others. The city of Srebrenica had 5,746 inhabitants, including 3,673 (63.92%) Bosniaks, 1,632 (28.40%) Serbs, 34 (0.59%) Croatians, 328 (5.70%) Yugoslavs, and 79 (1.37%) others. The most recent official data, those of the 2013 census, show the surreal number of 13,409 inhabitants including 7,248 Bosniaks, 6,028 Serbs, 16 Croats. 23 people did not disclose an ethnic-national affiliation and 67 declared themselves "other". Compared with the 1991 census (the last before the war), Srebrenica lost 23,257 citizens (63.43%), including 20,324 Muslims. Keeping in mind that you can declare yourself a resident even for electoral purposes only and that no more than 5-6,000 people really live in the entire Municipality of Srebrenica, including about 2-3,000 in the city (unofficial data), these are the results of ethnic cleaning and genocide. And the situation is no different in other parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Srebrenica is a traumatised community, destroyed in its identity continuity by the genocide, which has cancelled a part of its self. Destroyed from the point of view of socio-anthropological relations, it lives in a situation of suspension and conflicting narratives with respect to what happened during the war. Hasan Nuhanovic, translator at the Dutch blue helmets battalion, direct witness and promoter of the trial against the Netherlands for responsibility in the genocide, once told me: "Srebrenica has not yet resolved the balance between life and death. It is in the balance between being a dead city and a city of the dead. A dead city can come back to life, but a city of the dead will be so forever. Today there are more people buried in Potocari than living in Srebrenica”. And speaking of the victims of the genocide, almost thirty years later, there are still over a thousand people who have not yet been found.

This prevents several hundred families from moving on and keeps the community in a situation of suspension and waiting, which blocks any possibility of starting to process grief and individual and collective traumas. And this is a fundamental step, necessary before we can think of starting a dialogue, a public discussion on what happened during the war and on genocide.

Even today, finding a common reading of the past seems impossible. Just think of the refusal of Bosnian Serb political leaders to recognise that event as a "genocide". What are the reasons and obstacles that prevent a real reconciliation or, first, what is called a "shared historical memory"?

I do not believe much in the concept of shared memory, especially in contexts of coexistence of different communities within a given social space. I link it to artificial, political-institutional operations from above, often with little adherence to the reality experienced by the communities concerned, or the result of power play or colonial approaches to post-conflict. Reconciliation is the fruit of a long-term process. And every community should have the time to find a way to inhabit the complexity of its story.

I refer to the concrete experience of the late Sinan Alic and his foundation “Istina, Pravda, Pomirenje ” – Truth, justice, reconciliation. Here, the name indicates what I think are the milestones of the reconciliation process. Each constituent element of this hierarchical path represents a complex process in itself. The process of defining truth is complex and so is that of justice. Then there is the issue of the intergenerational war legacy, the difficulty in initiating processes of dialogue and public discussion on the so-called "Story of the other", before you can think of beginning a process of reconciliation.

This is the context of the project that we have just concluded with the Srebrenica Memorial and which was presented on 10 July as part of the events for the commemorations of the victims of the genocide. The "Srebrenica 2.0" project is funded by the MAECI (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation) and is a partnership between the Srebrenica Memorial and a network of Italian associations which for several years have built relationships with Bosnia and Herzegovina and with Srebrenica in particular (Arci Bolzano, Trentino, Florence, the Good Morning Bosnia Association of Venice, the Peace Center of Cesena, and the Zappa Theater of Merano).

It is a digital memory path , a downloadable App for mobile devices, which takes you to nine significant places in history to understand the unfolding of the main events that led to the genocide of July 1995 and was born from a series of observations and surveys in the field.

First of all, the need to find the way to bring memory back to Srebrenica as a place of history. The place of remembrance, or the Memorial of Srebrenica , is located in Potocari, which is a few kilometres from the town, while the place of history – Srebrenica – has basically no sign of public memory related to everything that happened there. Yet, Srebrenica was where the destinies of several tens of thousands of people unfolded from 1992 to 1995, until the moment of the genocide, which took place in other places than the urban area of Srebrenica.

This is a direct consequence of the substantial failure to initiate a dialogue and public discussion and each of the two communities involved has consolidated its own public memorial practices that do not communicate and compete. And it could not be otherwise because the situation, almost thirty years after the genocide, is that we are very far from starting a dialogue and a public discussion regarding war memories. The current Bosnian Serb municipal administration of Srebrenica, in line with the public discourse of the ruling political elites, openly denies the genocide. And the will is apparent on the part of the Bosnian Serb negationists to erase the traces, the places of history and to re-signify, changing their meaning, fundamental places for understanding what happened in Srebrenica up to the genocide.

Likewise, during the many educational trips carried out in the last decade with young people from all over Italy, the need emerged for multimedia supports to enable participants to build a visual-cognitive background to better understand the dynamics and developments of the war and how it came to the genocide of July 1995.

We also noted that Bosnian Serbs, especially the younger generations, struggle with physically entering the Srebrenica Memorial because of social pressures around the denial of genocide, which makes up the identity-constitutive narrative mainstream of their ethno-national group. To learn about the so-called "story of the other" does not mean being forced to change one's opinion, but at least acknowledging that there is another version than that of your ethno-national group and therefore perhaps adding complexity to the reading of what really happened during the war. A mobile phone app could facilitate private contact with the "story of the other", out of the group's control and stigma, and help to implement the public discussion on war memory(ies), which would otherwise remain locked up in the watertight compartments of conflicting narratives.

Then, with respect to the denial of genocide, it is an understandable mechanism. First of all, it is an integral part of the so-called Ten stages of genocide and then it is an individual and group self-defence mechanism. Who would admit to having committed a crime of this magnitude or that this atrocity was committed in the name of the national group to which they belong? Admitting it would mean to admit that the founding ideology of what later became the Republika Srpska was criminal and that this territorial entity, recognised by the international community with the Dayton Agreement, is founded on war crimes, on ethnic mass rape, on mass graves and genocide.

In October, all citizens of Bosnia will be called to the polls in what promises to be the most tense and complicated election in recent years. Do you believe that the commemorations of 11 July could be a springboard for an electoral campaign inevitably based on continuous controversy and divisions?

This happens every two years since the end of the war, because every two years in Bosnia and Herzegovina the four-year terms of political (national) and administrative (municipal) elections intersect and we can say that the electoral campaigns follow one another without interruption. Srebrenica is obviously in the spotlight and especially around the commemorations of 11 July, war memories and tragedies are used by political propaganda like clubs during election campaigns. So nothing new under the Srebrenica sky.

An element of novelty are the tensions of the local and international context. I am referring to the Bosnian institutional crisis and the Russian-Ukrainian war. With respect to the local context, since last summer the (nationalist) representatives of two of the three Bosnian-Herzegovinian constituent peoples, namely the Croats and the Serbs have blocked state institutions for different reasons, threatening secession, demanding the establishment of a third entity, threatening the use of force to defend their national interests, causing strong internal tensions and the mobilisation of international diplomacy to try to govern the crisis with sanctions and other persuasive tools. The Russian-Ukrainian war has polarised Bosnian-Herzegovinian public opinion and the Bosnian Serb nationalist leadership has strengthened public discourse on the defence of Serbian citizenship and territorial interests.

In the centre of Srebrenica, a few days before the commemoration of the victims of the genocide began, a huge billboard appeared depicting Milorad Dodik, a Serbian member of the state presidency, shaking hands with Vladimir Putin. It reads: "Guardians of Orthodoxy".