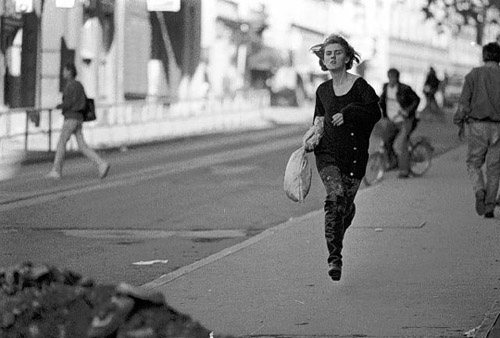

Sarajevo 1992 (photo © Mario Boccia)

Vivid and intense memories from the beginning of the siege of Sarajevo. Friends turning into enemies and loved ones leaving the city. Disbelief as the war starts tragically to unfold

Since reading that twenty years ago even the Bosnian General Jovan Divjak did not believe that war would break out in Sarajevo, I feel less of an idiot. I, just as the General, did not take the ominous signs, the unmistakable warnings, seriously. I did not believe them, I did not want to believe them. Even the day after the first attack on Sarajevo, between 5th and 6th April 1992, I continued to have my doubts. And as I did, so did many neighbours, friends, colleagues and relatives.

Sarajevo was attacked in the night of 5th April 1992 with the intention of dividing the city in two. All night we were bombed heavily, a relentless downpour of bullets was hitting the thin walls of the modern block of flats, we could hear the aggressors shouting sharp orders to each other: “This way”, “there”, “forward”, “back”.

On 6th April we woke up, so- to-speak, and met our neighbours outside our homes. Some were still in their slippers, others' pyjamas could be seen under their coats, women in dressing gowns, uncombed, all with bags under our eyes. The common feeling was “how dare they?”

We were asking ourselves which arms the empty cartridges lying around the building belonged to. There were so many that they formed a grey-brown carpet, an ugly one, even more displeasing by the river where it meshed in with the young light green grass, scattered with multicoloured primroses. We kept asking each other: “Have you seen?” “Did you hear that explosion around 2 am?”. We picked up the cartridges from the ground, examined them. The veterans of the Second World War, with more expertise, turned them around in their hands shaking their heads.

The conversation ended with “It was the papci who did it”, the cowards, or the local criminals, who had to be found and punished. Order had to be re-established and then life would continue as before. An hour later in fact everyone got back to what would normally be done on a sunny Saturday afternoon in April: mum went shopping, dad to his local café to sip coffee and read the newspaper, I went into town to meet up with friends.

In the following days of April attacks, more frequent at night, alternated with sporadic shooting during the day. The first foreign journalists arrived in the city. They were no less confused than us, they went around in groups, searching for the facts, the war. One of them called me asking me to be his guide. Three of them had arrived via Belgrade with a hire-car.

It was difficult to get through the city. It was obvious that people were confused and that the authorities had lost control of the situation. There were check points everywhere and barricades put up by whoever wanted to. Sometimes it was the neighbours or the people living on a certain street who were trying to protect themselves this way. New rules were established in the blocks of flats: the main door was locked and the neighbours took turns guarding them at night. Names were pulled off doors and letter boxes, we did not want to be identified, divided, we wanted to stay together, united in defence of our homes and our town.

Some barricades were manned by groups of young people. We were stopped by one of these groups. They were adolescents, some armed with old guns, others had sticks. They handled the sticks awkwardly unaware of the type of toy they had in their hands. Then I noticed they were passing a bottle of schnapps around. These kids were playing war. They asked for our documents.

I was not afraid, not because of any heroic feeling, but simply due to ignorance. I was pretty cross with them, because they had embarrassed me in front of my journalist colleagues. “What on earth do we look like in the eyes of foreigners?”, I asked myself annoyed. It was the image of my country that bothered me, not the imminent danger. They ordered us to get out of the car. At that point I understood: they wanted to steal it. Sarajevo TV had already broadcast news about gangsters making the most of the situation stealing what they could. The three confused and worried journalists looked at me and then back at the armed youth who were giving us orders. They did not understand the language, they did not know why we had been stopped, nor what was happening. I told them to stay seated and not to leave the car. I got out to talk to the kids who had stopped us.

For approximately fifteen minutes we talked, well, argued. They insisted that we get out of the car. In the end we reached an agreement, we would all go to an office together, a sort of post of command. Some of the youths got into the car, so we were ten in the car, in a space for four, others sat on the bonnet at the front or behind on the roof. Driving like a snail we reached the command. There a group of elderly people, who also appeared to me as if they were playing war, were passing a bottle of schnapps to one another. They wanted clarifications, asked stupid questions, in the end they slapped the journalists on their backs, some of them raising their fingers in the shape of the victory sign, one of them stammering in English: “Friends, friends”, and then another one asked the crucial question: “Have you got a cigarette?”

As a journalist, I felt the duty to inform my colleagues of the other side of the story: the point of view of those attacking us. I took them to Ilijaš, a suburb of Sarajevo. There the Serbs were in control, the Commander was a friend of mine. At least, he had been until the day before. I introduced them. I noticed that my friend, an engineer without a particularly successful career, was already wearing a uniform, but not the one from the Yugoslav army, it was the Serb one from the First World War. I exchanged a few words with him, trying to explain the difficult situation in Sarajevo, but he cut me off saying: “I know perfectly well, every day I speak directly with Belgrade”.

I did not want my presence to condition my Commander-friend's replies, so I left him alone with them. After approximately an hour, the foreign journalists came out of the Commander's office: their faces were shocked, as if they had just been on a roller coaster and did not feel well. One asked me: “Is he really your friend?” “Yes, I said without understanding the real motive behind the question. A short silence followed, and then one of them said:“He is a nationalist of the worst kind. He will exterminate you all”.

The bombings got heavier, the shooting during the day more frequent, the military planes flew low breaking the sound barrier. They were trying to scare us, In the grocery shops there was soon nothing left to buy, what had not been sold was raided. In the fruit and vegetable markets less and less was being sold.

The weather was - ironically – beautiful. For years there had not been such a nice and warm April in Sarajevo as in 1992. Instead of taking walks and enjoying the Spring, we remained more and more withdrawn in our homes and even in ourselves, in silence, troubled. Because of our fear we did not pronounce out-loud what was obvious: the war was on.

Even inside our houses the only topic of conversation that interested us was not mentioned. We thought about it, of course, but we did not talk about our worries. For fear, to avoid bad luck, hoping it was not true and it would pass quickly and that our suspicions were unfounded.

In the absence of news and official explanations voices spread, rumours, and what seemed improbable the day before would be confirmed on TV the day after. The Chetniks, the Serb nationalists, were in the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) barracks around Sarajevo.

The number of people escaping from Sarajevo was growing. The train lines had already been blocked for some time. People were escaping by car, on foot, on buses. I was to find out that Mladen had gone, that Emir had sent his wife and children to a safe place, that Milena had called from Belgrade, that Snježana had gone to her cousins' in Montenegro with all the family. “Just for a few days until things get better” Vlatko, our neighbour had said, leaving us the keys to his flat and saying "the fridge is full of food if you need it…”.

It was already the end of April, I had to go back to Belgrade: the leave I had taken “just the time necessary for things to get back to normal, once the misunderstanding was sorted ” was over. The airport was under Serb control, only special planes could land. You could not get close to it: approximately 5 km from it there were already many desperate people trying to escape. Whole families would camp in the area hoping to get on-board. The destination was not important, the only thing they wanted was to leave Sarajevo that was becoming more dangerous by the day. That mass of people were pressing the cordon of Serb soldiers who were protecting the landing and take-off strip.

I had a Belgrade radio and TV pass: a Serb one. It helped me get a place on the plane, a special Boeing without seats, a so-called Kikas, from the name of a patriotic Croat who had bought it and sent it to Croatia full of arms. It had been confiscated by the JNA and used to transport fleeing civilians.

They loaded us onto a bus in the centre of town, after having carefully checked our documents. Escorted by the police, the bus headed towards the airport. We were often stopped, the driver showed his permit and then we continued. Near the airport the bus was swallowed up by the mass of escaping people. We could not move. We were still and surrounded. The tension was incredibly high among us inside and among the people pushing from outside. They were trying to get into the bus, as it was the only way to get to the airport, the way out. Many were shouting, threatening us, hitting the bus, some grabbed onto the sides of the windows, there were mothers lifting their children towards the windows pleading with us at least to let the youngest on-board. In the bus some were crying, others were afraid and covered their eyes with their hands so as not to see such scenes, others crouched down shying away from the looks of those desperate people or to protect themselves. It felt like we were living through one of those fleeing scenes from Saigon, before the final attack on the city, during the Vietnam War that I had seen in documentaries.

Finally the bus drove right onto the take-off strip and stopped by the steps up to the plane. Still shocked by what we had seen, we got off quickly and ran up into the aircraft. Behind me there was a pregnant woman, I politely let her get on before me. Then it was my turn. But a man who was surveying the entrance said “It's full, there is no more room”. I could not believe it, I started to complain. The plane was a big Boeing and it seemed impossible to me that there was no room left for one person. I showed my journalist's pass. The man let me look inside the plane: it was overflowing, crowded, all were squashed like sardines in a tin, sitting on the floor. In the toilet there were three people and a child was sitting on the sink, there was no room left, not even for a pin.

I gave up.

I left Sarajevo that same evening, on a small military plane that had brought some medicines from Belgrade. In the fragile rocking aircraft we could hear the explosions and the shots coming from the city. That noise continued to reverberate in my ears for the four following years, the siege of Sarajevo lasted 1427 days of, the longest siege in the history of modern Europe.

To Top

To Top