My Places | Parque Lage (Leonardo Chaves, Flickr )

The photographers who documented the Balkan wars have contributed to shaping the memory of those events, and, in some cases, also the history. The destiny of a photo, however, is not in the hands of its creator

For twenty years I went to do all my document photos at “Ðumišić” the photographer who still has a small shop in the centre of Sarajevo. I had chosen him for a precise reason. He touched up the photos really well, at the time it was called a retusche, and on the photos we all came out perfect – no wrinkles or spots, with a face as smooth as porcelain. I still have one of those photos, for my passport, an image so “air brushed” I can hardly recognize myself: fine eyebrows, thick hair, large eyes and long lashes...I look like a doll!

In the sixties cameras were still quite rare in our part of the world. My uncle had one – he was an engineer who worked abroad. When he came to visit he took photos of each of us, one by one, and we were expected to see this as a kind of present or special event. One of the photos of me was displayed for a time on the sideboard. “So you can see how ugly you are when you scowl”, my father said. I was only little and, though I didn't like this way of being treated, I could do nothing. After that I chose the photographer “Ðumišić” who, in his photos, made me look perfect.

In the past, personal and family photos were seldom taken, once a year at most, or on a special occasion like a birth. In our family this meant every two years when one of we six sisters was born. For the occasion, the local photographer was called in to immortalise the event.

The photos of my parents are missing for the 1940s when, during the Second World War, they were partisans. Apart from medals and some thin, yellowing scraps of paper with the hand-written orders of their commander, there is no other proof of their participation in the war. A pity. I would have liked to see a photo of my mother when she stood as a young partisan in the centre of a village and sang, in an attempt to show the locals that partisans were not bad people. Or a photo of my father as a partisan, as I imagined him: looking more or less like Che Guevara in that famous photo of him wearing a beret.

If other families like ours only had their photos taken every one or two years or for special occasions, I wondered how photographers managed to earn a living. I got the answer when I was no longer looking for it and at the least likely moment: during the last war in Bosnia Herzegovina.

Alija's archive

One of these selfsame photographers that “I didn't know how they managed to earn a living”, from the Bosnian town of Višegrad, told the weekly “Bosna” that just by taking document photos and photographing important family events did he get to the end of the month.

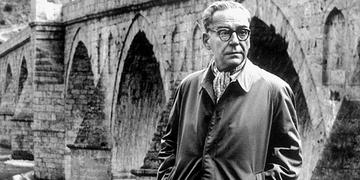

To tell the truth this photographer, Alija Akšamija, was not just anybody but a real master, and his dream of taking a photo which acquired a symbolic status was achieved. He took the famous photo of the Nobel prize winner Ivo Andrić, portrayed beside his inspiration, the bridge of Mehmed Pasha Sokolović in Višegrad.

For many years that photograph was reproduced across the world, appearing in anthologies, monographs and magazines and it became the emblematic image of the author. Even so, for a long time the identity of its creator remained unknown, until one day it appeared with the signature of Alija Akšamija.

Taken in 1963, that black and white image is still striking today. With the passage of time it has lost none of its strength, vivacity or poetry, still evoking the symbiosis between the writer and the bridge over the Drina. Even in the case that Akšamija had never taken another photo, this would be enough to make him an artist.

In the Bosnian media, however, Alija Akšamija was featured speaking of something else related to his profession, useful, but unexpected. During the war, Akšamija escaped from Višegrad and took refuge in Sarjevo. In his town thousands of Bosnian Muslims were killed, raped and burnt, and still over a thousand are missing. Those who survived talk of criminals, know the names and nick-names of the assassins and can describe them. But in many cases the culprits, the torturers, the thieves and the rapists are still unidentified.

The photographic archive that Akšamija managed to save as he fled Višegrad became useful, since, by carefully scrutinizing the film, photos and negatives, in certain cases names could be attributed to the faces of the culprits. Sometimes they don't have to be looked for in photographic archives or in the “mug shots” held by the judicial authorities. Often the monsters, proud of their heinous offences, have their photos taken alongside their victims as they carry out their crimes, shoot to kill or torture, assault and destroy. One example which became a symbol shows the police chief of South Vietnam, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan as he summarily executes in the road a suspected Vietcong prisoner, Nguyen Văn Lém, in Saigon in February 1968.

An almost identical photo was taken during the war in Bosnia in April 1992 by the American photojournalist Ron Haviv which shows the assault on the town of Bijeljina by the Serbian paramilitaries commanded by the infamous Željko Raznatović “Arkan”. The photo shows a terrified civilian begging for his life. His fear is almost tangible, his gaze begs pity, his shoulders dropped (to protect himself from blows?) his hands (trembling?) raised high. Every time I look at that photo I feel shock and fear, as if what happened twenty years ago is about to happen now. I feel I can hear the voice of the victim crying. I look at the photo and think how the man must feel, knowing he's about to be executed.

Many infamous criminals, when the time comes to acknowledge their “heroism” immortalized in the photos, try to deny it, to “explain the context”, they talk of a “misunderstanding”, accuse the witnesses of having interpreted it wrongly, or not seen it well, criticize others for falsifying, threaten...

Vedran in Vijećnica

A word stated before witnesses and in public can be contradicted or denied. A photograph is pitiless, an invincible document, a solid testimony.

I am convinced that a certain Jelenko Mićević, alias Filaret, Bishop in the Serbian Orthodox Church, would give anything to make the photo taken in 1991 on the Croatian front disappear – it portrays him in front of an armoured car holding a kalashnikov. And not only him! In 1992 in Belgrade I witnessed a group of lobbyists for the Serbian cause discussing whether to make big posters of a mujahideen immortalized exhibiting the decapitated head of a Bosnian Serb during the Bosnian war.

Unlike what is thought or believed, the images “steeped in blood” are not necessarily those that shock the most. When faced with images which are too cruel, we turn our gaze elsewhere; we can't stand it. Our message is: “I pity you, but I can't stand to look”.

For instance, the photos of the massacre of 22 people queuing for bread in Sarajevo in 1992, where everything was covered with blood, had far less impact on public opinion than the photo of a cellist of Sarajevo, Vedran Smajlović: in evening dress, ignoring the bombing and snipers in besieged Sarajevo, Vedran played the Adagio in G minor by Tommaso Albinoni for twenty-two days, one day for each of the victims killed in the bread queue. The image of the cellist was much more explicit and expressive of what was happening in Bosnia, compared with the many photos of horror, death, destruction and suffering. “A people under artillery fire manage to retain its humanity” - with these words the New York Times published the photo of the cellist.

The photo which became the icon of the betrayal of Srebrenica by Europe, the USA and the United Nations and which finally changed the American position on the war in Bosnia, is the one showing a young Bosnian woman, Ferida Osmanović, who hung herself in the woods after the town had been taken by the Serbs. This photo was shown during the debate on Srebrenica in the American congress, and had a decisive impact on the politics of the United States in Bosnia. At first sight the tragedy revealed in that image is not apparent. One sees just a young woman standing in the greenery of the wood; it seems almost idyllic. Only by looking closer can it be seen that her feet aren't touching the ground and her body suspended.

Another symbolic photo of the war in Bosnia shows a Serb paramilitary who, in the town of Bijeljina, is kicking the head of a Bosnian woman, already dead and stretched on the ground next to two other victims. It was taken by the American photojournalist Ron Haviv, who, with the permission of criminal Arkan, photographed members of the paramilitary, the so-called “Tigers”, during their attack on Bijeljina. One of them is young, tall and slim, a rocket-launcher on his back, a kalashnikov in his right hand, a lit cigarette in his left, a balaclava tucked into his jacket and sun glasses on top of his head. This young man in comparison with his rough colleagues “thirsting for blood” (by the look on their faces), seems like a city dweller, more refined. Yet it is he who, with his raised right black boot, is about to kick the dead woman in the head.

The contrast between that refined figure and the malicious gesture gives one the shivers. He does it with ease, as one would kick an empty can or a passing ball while walking near the park. Furthermore, that young “townsman” did it knowing he was being photographed, as Ron Haviv the photographer has testified.

A story for every photo

Behind every photo there is a story, writes Susan Sontag in her famous book “On Photography”.

The cut-off head the mujahideen was photographed with belonged to a Bosnian Serb, Blagoje Blagojević, who was captured in central Bosnia in 1992 and decapitated. The Islamic fighter who had his photo taken with the cut-off head was a French citizen, Christopher Kaze, who had converted to Islam and arrived in Bosnia at the beginning of the war. He was killed in a fight with the Belgian police.

The young woman of Srebrenica, Ferida Osmanović, hung herself in the country near Tuzla, on July 11th 1995, after her husband had been seized by Bosnian Serbs. Just a few days previously she had convinced him to stay with her and their two children, instead of fleeing into the woods. She was buried as unknown and, only six months after her death, identified by her children from the only photo they had of her.

The civilian who was begging for his life was called Hajrus Ziberi. In April 1992 he was twenty four years old and had been married for just three months. The day the photo was taken he was on his way to work, but, captured by the “Tigers”, he was thrown down from a building and, though he survived, he was then tortured and killed. His body was thrown into the river Drina, fished out in the Serbian town of Sremska Mitrovica, buried as unknown, then exhumed and identified in 2004, and finally buried in his town of origin in Macedonia.

The woman who was kicked when dead was called Tifa Šabanović. She was killed in front of her own door along with her husband and a neighbour. For a long time it was not known who that “refined” paramilitary was. His face was not known. The photo shows him from the side. Following his arrest in Belgrade for possession of drugs and firearms, it was “discovered” that his name was Srđan Golubović. After Bijeljina he had not hidden – on the contrary he was in the spotlight of the music scene in Belgrade. He had substituted the synthesizer and record player for his kalashnikov and rocket-launcher. His stage name today is DJ Max and over the last twenty years he's made his career with Trance music and “after party”. His sessions are said to be among the best in the Serbian capital. Srđan Golubović, alias DJ Max, “is one of those who let you, after every party, go on having fun” was how he was described, this “fine” youth, the “townie” who, after kicking a dead woman in the head, had continued to have fun.

Twenty years after the famous photo was taken, Srđan Golubović was arrested. Not for war crimes, however, but for drugs and undeclared firearms. And, not much later, he was released.

To Top

To Top