The role of partisan cinematography in Socialist Yugoslavia and what happened to two of its better known exponents – Bata Živojinović and Hajrudin Šiba Krvavac, hero and director respectively of the most famous Yugoslavian film in the world, “Valter defends Sarajevo”

A youth, one of the third generation, published on the net a family photo from the 80s with the caption “The Supreme Command” close to the image of his grandparents (the first generation), who were posing together with their children (the second generation) and grandchildren (the third).

An explosion of laughter at an international level followed, since the last war in Bosnia has scattered us abroad over five continents. I laughed to see that even the grandchildren knew we joked about our parents/grandparents, all partisans, calling them the supreme command.

The retired guerrillas of the Neretva

Our parents were not the kind to pester us with stories of their activities as guerrillas. The war had left my mother with the fear of hunger. That's why she bought more bread than we needed. I told her off for the waste but she still hid two extra rolls in the cupboard, in case.

My father, on the other hand, when he taught us how to be honest and dignified in our life, spread his hands and said, “I came out of the war clean, stole nothing and hurt no-one.”

We witnessed a transformation in these calm and ordinary pensioners for a brief and intense moment at the end of the 60s. Out of the blue, that gentle grandmother and soft-hearted grandfather stopped talking about their grandchildren, complaining about their rheumatism or their meagre pension.

They became resolute, showing a hard, combative character and unsuspected vitality. They talked in military terms, of strategy and advances, of brigades and Germans, of orders and – exactly – of the supreme command.

It all began at the end of the 60s when “Bitka na Neretvi” (The Battle of the Neretva) was being filmed in Bosnia. A gigantic and costly project. Important international actors were performing, like Yul Brynner, Hardy Krüger, Franco Nero and Orson Welles, the best Yugoslavian actors and more than ten thousand soldiers from the ex Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). Pablo Picasso contributed one of the posters.

In the real battle of the Neretva, during the Second World War, my father was one of the commanders. My mother, ill with typhus, was among the four thousand wounded that the partisans took with them as they retreated from the offensive of the German, Italian, Croat Nationalist Ustashi and Serbian Cetnic forces.

My father was called in as a consultant for the film. Enjoying his renewed importance, he pulled out all his wartime objects which he kept in a wooden trunk, once used for ammunition, and he reread the jottings, examined the documents and orders. My mother took out their medals, polished them and, for the first time, talked at length about what they'd been through.

The film “The Battle of the Neretva” was nominated for an Oscar as the best foreign film. More recently, at the Moscow Film Festival, it was included in the ten most important films on the Second World War from among 120 films on this theme from all over the world.

Valter defends Sarajevo

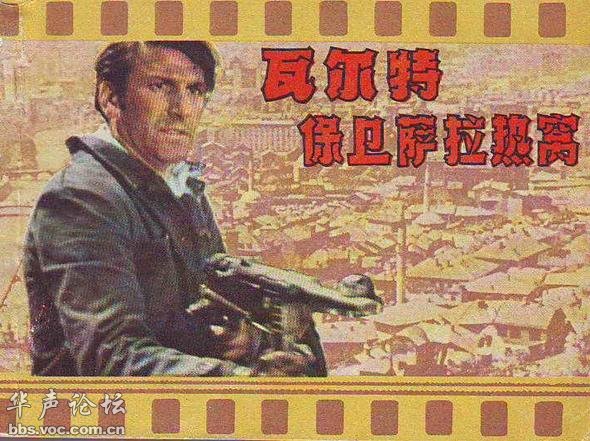

“The Battle on the Neretva” is a film of high artistic value. Even so, it is not the most popular film in Yugoslavia's partisan cinematography. Another film, “Valter brani Sarajevo” (Valter defends Sarajevo) has been seen by nearly a billion people across the world. It's a “spaghetti western” type of film, made forty years ago and which still enthrals audiences of hundreds of millions. A fable about the partisan guerrilla warfare in Sarajevo during the Second World War. Its hero, code named Valter, defends Sarajevo and manages to avoid capture despite the efforts of the German occupying forces.

Valter really existed. His true name was Vladimir Perić. He was a partisan, a leader of the resistance in Sarajevo, killed in 1945 and then declared a popular hero. His monument is still in the city centre, near the Skenderija crossroads.

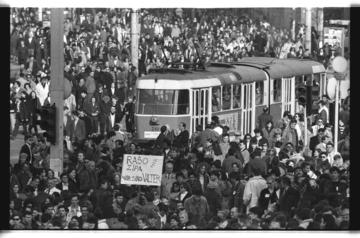

The film about him is still very popular in China where it has been shown many times on national television. Some estimates claim every Chinese adult has seen the film at least thirteen times. “Valter defends Sarajevo” is so popular that during the NATO bombardments of Serbia, in 1999, over fifteen million Chinese wanted to go and defend “Valter and his country”.

They had not understood that Valter was Bosnian.

Bata

The role of Valter was played by the most popular actor in Yugoslavia, the Serb Bata Živojinović. That role earned him fame worldwide. Today Valter, that is Bata, is still revered on the Asian continent and in all former communist countries. Bata Živojinović continues to enjoy the position of hero in his films and benefit from this, particularly in China, where the smallest of the “Valter” fan clubs can count twenty five million members.

In the 90s Bata Živojinović left his hugely popular acting career to enter politics: he became, and remained for seventeen years, a member of Slobodan Milošević's Serbian Socialist Party (SPS). In the bloodiest and most criminal phase of the SPS, during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bata Živojinović was a candidate for the presidency of Serbia. But Slobodan Milošević preferred a more radical appointee, Vojislav Šešelj, today at The Hague accused of war crimes.

“I have always been red (of the left),” Bata Živojinović says, to explain his membership of the SPS Party, a Party that was red not for its political orientation but for the blood of brothers shed for its expansionist ambitions.

Lately, Bata celebrated his seventy seventh birthday, and a career of fifty years, giving numerous interviews for the occasion: a happy and satisfied man.

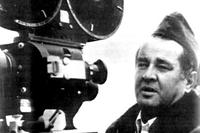

Bata Živojinović was a hero for many of us Yugoslavs, when the films about partisans fascinated us, and this feeling was intensified by his role as Valter. The director of the film, to which Bata owes his great popularity and continued earnings, is the Bosnian Hajrudin Šiba Krvavac.

Šiba

In one of these interviews, the actor recounted his great friendship with Šiba, “a good and admirable man, very tolerant and with a great sense of humour”, and of having been best man at his wedding. Bata declared Sarajevo to be his second favourite city and Bosnia his second home, which had given him his chance in life, and that he had always been close to Bosnians.

As we know, however, destiny sometimes puts us to the test and takes cruel twists.

During the war, Bata spent seven months in Pale, the stronghold of the Bosnian Serb rebels, filming a comedy. According to the press, from there the actor/politician urged “bombing the Turks for twenty five hours”. He himself tells of being on the mountains above Sarajevo and seeing the cannons bombing the town, and presumably also his friend Hajrudin Šiba Krvavac, who was in besieged Sarajevo at the time.

It is shocking how lightly and indifferently Bata speaks of the fate of the film director who had given him his “chance in life”. Hajrudin, “the friend he adored”, Bata Živojinović, as a politician, describes as “an orthodox Muslim”. To the question as to what end Hajrudin Šiba Krvavac met (he died in 1994 from a heart attack), Bata replies casually that he doesn't know and he “probably died of hunger. . .” He seems not to realise or care about the cruelty and banality that emerge in his words. Asked if he was aware of being part of the policy which produced “Sarajevo, Srebrenica, Vukovar and Dubrovnik”, that is genocide, destruction and death, Bata answers that in the SPS he was a simple pawn and had entered only because the door was open. When the journalist tried to help him, asking, “Were you tricked and used by Slobodan Milošević?”, the famous actor replied: “No, no. I didn't enter politics as anybody else. I had a name, a career.”

Valter alone is eternal

With the end of the war in Bosnia, and passing of time, hostility is diminishing, ties are renewed between enemies until yesterday, friendships are recreated, biographies cleaned up, embarrassing and awkward statements are explained, misunderstandings discussed. To hate the Turks, that is Bosnian Muslims, is no longer the fashion. Bata Živojinović also complies. “Everything passes, Valter alone is eternal,” he recently told the newspaper “Jutarnji” in Zagreb.

In the film “Valter defends Sarajevo” there is the legendary final scene in which one Nazi officer asks the other who the mysterious Valter is, and the latter answers pointing from a hill top to the whole of Sarajevo, “That is Valter”. Like a great metaphor, this phrase has been used repeatedly in various contexts, often during the siege of Sarajevo.

Today Bata Živojinović, “Valter”, is defending Sarajevo again.