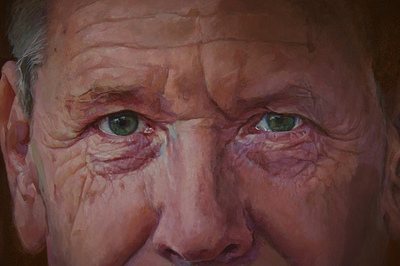

Amos Oz, portrait (M. Benard/flickr)

Amos Oz is one of the best-known names in world literature. An Israeli novelist, essayist, and political activist, Oz is a fervent supporter of the need to reach compromise in order to overcome conflicts. Our correspondent met him in Sofia

Amos Oz, novelist, essayist, journalist, and political activist, is one of the most influential and respected intellectuals in Israel and his name is one of the best-known on the world literary stage. A several-time candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Oz is the author of successful novels such as “A Tale of Love and Darkness”, and “To Know a Woman”. His essays include the Tubingen Lectures, a trilogy of lectures, published in Italian under the title “Contro il Fanatismo.” [the title of the original is The Tubingen Lectures. Three Lectures, translator’s note]. Directly involved in the debate on the Israeli-Palestinian question, Oz has always been a supporter of reaching compromise and was among the first to support the idea of creating two separate states, Israel and Palestine. Oz was a guest of honor at the Sofia Book Fair, held in the Bulgarian capital in December, where he presented the Bulgarian translation of his “Rhyming Life and Death”.

This is your first time in Bulgaria, but you said to have visited it many times “in your dreams”. What did you mean by that?

I grew up in a part of Jerusalem where many of the residents were Jews from Bulgaria. For us Jews, Bulgaria is a special place and we will never forget our gratitude to the government, but above all to the Bulgarian people. A large part of the Jewish population in the country was saved from the Holocaust. Even before World War II, the Jewish community enjoyed particularly good conditions in Bulgaria. In one of my books, “The Same Sea”, many of the characters are actually Jews from Bulgaria.

You come from a country marked by conflict, and you have been one of the first and most convinced supporters of the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Do you think this can be achieved, considering the current conditions?

When we started considering this possibility, there weren’t many on either side who supported it. Today, however, I believe that most Israelis and Palestinians are ready to take this step. I am not saying they are enthusiasts. When and if two separate states are created, there won’t be celebration or dancing in the streets. But I am convinced that by now there is a strong awareness that this is the only way out. The time has come, to put it like this, to divide the house into two smaller apartments.

What are the obstacles to making this happen?

I will use a metaphor from the world of medicine. The Israelis and the Palestinians are like a sick person who has come to accept that in order to get better he/she must undergo surgery, no matter how painful it might be. The problem is that the doctors who should be the lead surgeons are too afraid to enter the operation room. Then, there is the problem of the fanatics who, on both sides, fight against compromise.

Compromise is a word which appears a lot in your political vocabulary. What does “compromise” mean for you?

The concept of compromise is not particularly in vogue, especially among young idealists. This is because it is perceived as an immoral agreement; as a betrayal of pure and absolute principles. For me, however, compromise is a synonym for life. “Compromise” does not mean to surrender or to turn the other cheek, but to succeed in meeting the other half way. The opposite of compromise is not idealism, but fanaticism, which is equal to death.

You have dedicated many pages to fanaticism, and a book [“Contro il fanatismo”, 2004, published in Italy by Feltrinelli]. In your opinion, where are the roots of fanaticism in the modern world?

Fanaticism today derives its force primarily from the extreme complexity of the world we live in. In this complicated world, fanatics have simple, prompt answers - often a single phrase or slogan. These are answers that can attract certain categories of people. The fanatic, to use a literary metaphor, is an exclamation mark walking among us. I believe that the 21st century is not so much a clash of civilizations as much as a struggle against every form of fanaticism, be it Islamic, Hebraic, or Christian.

If current leaders do not have sufficient courage to resolve the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, do you see any alternative leadership on the horizon that might be able to continue this process?

It is difficult to say. Changes often happen in mysterious ways and it is impossible to predict who could change the world. Who, in France, would have believed that it would be De Gaulle himself to pull the country out of Algeria? And who among us would have believed that Sadat would come to Jerusalem to sign the peace deal between Egypt and Israel? At the moment, I have no clue who might be able to put an end to the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, but I am sure of one thing: whoever does it will rightfully go down in the history books.

You claim that one of the basic roles of culture at present is to preserve memory. You don’t fear that there are also “bad” memories that can make the resolution of conflicts more difficult?

I think that today there is a global clash between culture and the enormous economic machine which is literally trying to wash our brains. From dawn till dusk we are bombarded with messages trying to convince us to throw away what we have because the only thing that really matters is only what we still have not managed to buy. Thus, the past should not have any value and it has to be thrown away. I think that the role of culture, in some way, is precisely to make us remember what we are trying to forget. As for the role of the memory of conflict, I think that the problem is not how to forget the traumas and the suffering. These memories are also valuable and should not be feared; the important thing is not to become their slave.

You have often emphasized Europe’s special responsibility in the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Where does this conviction come from?

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has its roots in Europe; both peoples were its victims. One suffered a history of discrimination which culminated in the tragedy of the Holocaust. The other bears the memory of European oppression and colonialism. It often happens that two brothers raised in a violent family do not like each other at all because they tend to see a reflection of their ancient oppressor in each other. This is exactly what is happening between our peoples today. Because of this, Europe has great responsibility. This does not mean taking the side of one or the other, but helping both find the road to peace.

Conflicts also feed on symbols, and symbols can become the cause of conflict. In these past few weeks there has been a lot of discussion in Europe about the referendum in Switzerland banning the construction of minarets. What do you think of this?

I think the result of the Swiss referendum was awful and the reason is simple: I am convinced that anyone has the right to build as many mosques, churches, or synagogues as they please.

To Top

To Top