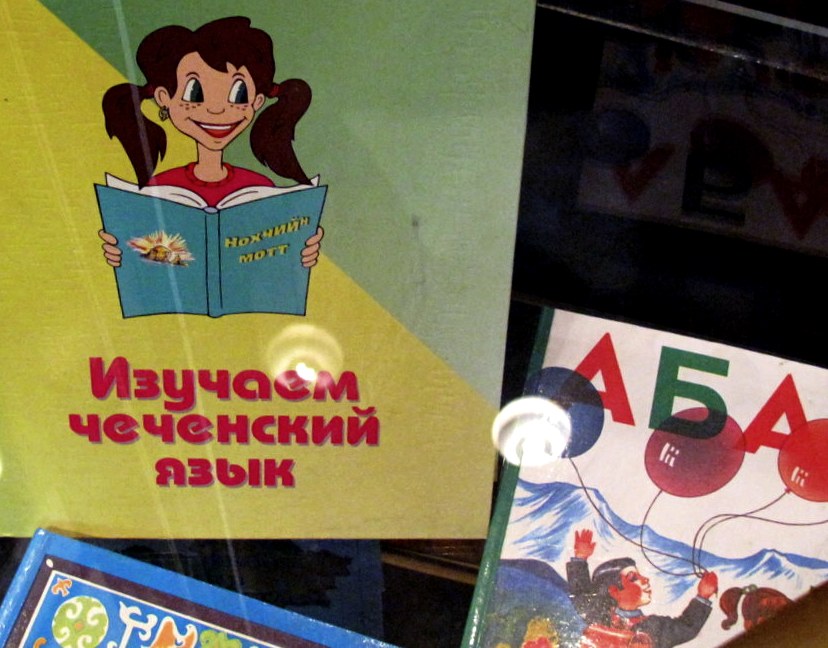

"Let's study the Chechen language" (ifl/flickr )

Chechnya recently openly celebrated Chechen Language Day, but Russian is still the country's official language and fewer and fewer Chechens are fluent in their own mother-tongue

What's our word for “table”? This apparently trivial question is among the most often found on the online forums where Chechen youths gather to learn at least the basics of their mother-tongue. Although there are several Chechen synonyms available for the piece of furniture that dare not speak its name, only a select few are aware of them. The reason is that people, in their daily lives, speak a peculiar blend of Chechen and Russian, with vocabulary from the latter dominating. This language use pattern became common in the decades in which Soviet and Russian language policies aimed to suppress Chechen out of the fear that allowing Chechens to speak their own language would instill the germs of national identity or aspirations to independence in the “people of the mountains.” The result is that, nowadays, very few Chechens are able to express themselves clearly and effectively in their mother-tongue without resorting to using Russian words.

Soviet Chechnya

In Soviet times, only Russian was used in schools. Speaking Chechen was forbidden, although there was no official law banning the language, nor is there today. Despite lack of an official ban, any attempt at speaking Chechen at school, at work, or in public spaces was repressed by Communist Party supervisors, always on the look-out for “nationalist tendencies”, which by definition included the desire to speak in one's own language. I still remember how any Chechen word uttered on public transport immediately stirred aggressive reactions from the Russian-speaking folk. “This is not proper. This is not some cave where you can speak your barbarian language”. Such reactions were the friendliest reproaches administered by those representatives of Chechnya's “elder brother”.

Even though the Soviet Union has sunk into oblivion, its legacy of silently destroying national languages survives. In contemporary, “democratic” Russia, exactly like in the past, national minorities have no chance to preserve, let alone cultivate, their own languages. As is well known, the only way to save a language is to speak it – everyday, in daily-life situations – and develop its written form. But this is impossible as long as Russian remains the only official language because all bureaucratic protocol, documents, and laws are in Russian. The Chechen language, banned from the public sphere, is doomed to extinction. There currently exists only one Chechen-language newspaper, although it has just a few readers and is written in an artificial way modeled after Russian. Furthermore, Chechen people have to use the Cyrillic alphabet, one that hardly adapts to the specificity of their language. They had traditionally used the Arabic alphabet, adapted to Chechen phonetics, and there was also a period when Latin was used. After the October revolution, however, all the language minorities of Russia had to switch to Cyrillic. Even now, the Constitution of the Russian Federation prescribes for all peoples the use of Cyrillic.

A language in danger

Some years ago, UNESCO included Chechen on its list of endangered languages. Since then, nothing has been done by Russian authorities or their local representatives to save one of the oldest languages in the Caucasus. The few initiatives by the Chechen government have been crushed by the Kremlin. For instance, a few years ago, the Ministry for Education introduced Chechen in primary schools with the explanation that families traditionally spoke Chechen at home and young pupils thus struggled to attend classes in Russian. But Moscow publicly disowned the idea right away by declaring that Russian, as the Federation's official language, should remain the only language of instruction in schools, be they located in Moscow, Chechnya, or Siberia.

Local authorities were left with no other choice but to withdraw the initiative as “premature”. In turn, they tried to make up for the embarrassment by establishing “Chechen Language Day”. On a specified day in April, all state employees must show up at work wearing the Chechen national costume, not worn since the 19th century and which can occasionally be spotted on folk dancers. It is not clear how this celebration relates to language – after all, the day is not named “Traditional Costume Day.” And yet, this is what it looks like: the government plans to save the national language by hanging a couple of banners here and there and by making people wear folk costumes and wander around town like mimes.

Over the last few years, the situation has only gotten worse. During the long war years, many people who could have passed on the literary language died. The elderly, who speak a language still uncontaminated by Russian neologisms, are disappearing. Over 100 thousand young people have left for Europe, a place where they seldom have the chance to speak their mother-tongue. Since Chechen emigration is a relatively recent phenomenon, the diaspora has not yet managed to establish schools or courses where the language can be taught and learned. It will probably take some more years, but the need to preserve and develop the Chechen language is urgent. This is why young people, scattered all over the world, go online to share their ever more modest knowledge and wonder how to say “table” in their own language.

To Top

To Top