Rijeka/Fiume (foto © Leonid Andronov/Shutterstock)

Combining scientific research, dissemination, and participation; telling the story of Rijeka in multiple languages. These are the objectives of an international project of which OBCT is a partner, in view of Rijeka – European Capital of Culture 2020

The official proclamation of Rijeka as European Capital of Culture for 2020 is just a few weeks away. Preparations are in full swing, many actors have been mobilised, and the official presentation ceremony of the programme of activities for the next year was held on October 30th. At the same time Rijeka, its identity, and its history remain at the centre of debates in Croatia and Italy. Although the controversies around the centenary of D'Annunzio's enterprise have been archived, at least by the media, the city is back under the political spotlight in view of the upcoming presidential elections. In this case, the controversy was sparked by Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović's comments on the local soccer team. During a speech in Split, the Croatian President had called the Rijeka of the 1980s a satellite team of Partizan and Belgrade's Red Star. Reactions to such allegations of lack of Croatian patriotism prompted Grabar-Kitarović, who is originally from the area, to quickly back off. However, it seems that the different interpretations of the city's complex history and the slogan "Port of diversity", chosen for next year's event, will not fail to stem new controversies and exploitation.

In the last few weeks, Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa has become official partner of a large international project dedicated to the history and memory of the city of Rijeka. The leading body is the University of British Columbia Okanagan, but the project involves scholars from different countries and other institutions such as the Department of Cultural Studies of the University of Rijeka and the Center for Advanced Studies – South East Europe. Last July, this very institution hosted a widely attended international conference, aimed at framing the Rijeka events in the wider experience of those regions and cities – in Europe, but not only – that have changed sovereignty following border displacements.

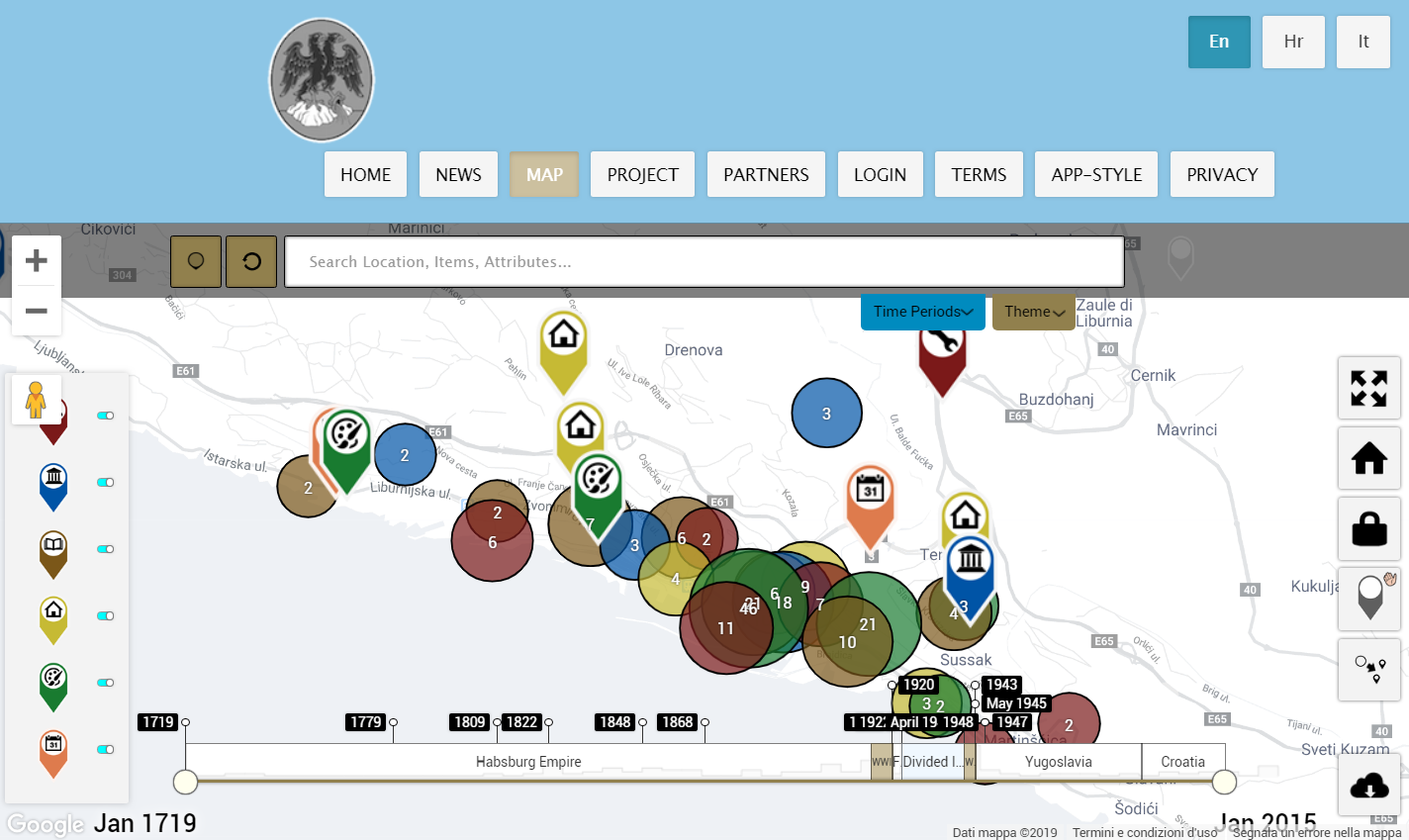

In addition to studying Rijeka's history after the Second World War, the project seeks to foster the active participation of citizens and communities in the reconstruction of the city's events. This approach lies at the basis of what is called Public history – a discipline that has started a reflection on the importance of historians opening up to collaboration and dialogue with professionals from other disciplines of disseminating knowledge and above all with the public, “sharing authority", but without giving up its own analytical rigour. In line with this vision, the research team has launched an interactive online map that allows anyone to add fragments of history and memory of the city. This is a central aspect of the project, which aims to fill this common container of Rijeka stories as much as possible. Already today, navigating the map, it is possible to draw on images, audio files, and texts uploaded by users in different languages (Croatian, Italian, and English): to discover new places such as the site of the old Orthodox city cemetery, today a playground; to see the original projects of the “Giardini” fascist district club, which now houses the headquarters of a local company; to read the story of David Cherbaz, executed in 1945 by order of the Yugoslav Army Court with the accusation of having collaborated in the destruction of the great city synagogue in 1944; or to find the graffiti dedicated just a few years ago to Croatian composer Antun Mihanović.

In collaboration with researchers from different disciplines, a second product is also taking shape: a smartphone app which makes the results of research carried out by the historians involved available to citizens and visitors who want to explore Rijeka in the coming months. The team is currently working on the assembly of materials. It will be possible to get acquainted with lesser-known features of Rijeka's most famous places: from the Governor's Palace, a key place of city power, to Tito Square, built after the Second World War to unite Rijeka with Sušak – but also places that are mostly ignored, the specific interest of which emerged following the different research streams. The app will not only allow access to old documents and materials, but also to follow thematic itineraries focused on specific aspects of the city's history.

Brigitte LeNormand, associate professor at the University of British Columbia and principal investigator of "Rijeka in flux", explained the genesis of the project and its evolution to Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa:

1) Can you tell us how the history of the city of Rijeka has become the central subject of an important project in a Canadian University?

Canadian universities, and the University of British Columbia in particular, are global in orientation. Rijeka is a case that raises interesting questions that move beyond the specificities of its local context. What impact do border changes have on places? The twentieth century is rife with cases of changing borders and sovereignty. In researching Rijeka’s history, we can develop theories that can be applied to other cases. In developing the Rijeka in Flux app, we are also asking: how can we communicate knowledge on contested cities in effective and yet open-ended ways, that engage people in making sense of complexity? Our app will similarly be adaptable to many other contexts. But for me, as a historian, the case of Rijeka is inherently interesting – a city that experienced multiple border changes, and enormous demographic, economic, and ideological change after the Second World War.

2) The project is called "Rijeka in flux", what is the basic idea behind this title?

It’s a play on words – Rijeka and Fiume, the two names of the city, both mean “river,” and “flux” refers to flowing. There is a deeper meaning, however – research on cities that have experienced border changes has tended to focus on the top-down remaking of the city through urban planning, architecture, and the appropriation of what is inherited, for example, by changing street names. While holding on to these insights, we want to think about other ways that borders change cities – especially, the ways in which they embed cities in new networks, and alter the flow of people, goods, ideas, and capital. My own research within the larger project focuses on Rijeka’s transformation into socialist Yugoslavia’s main port, and the impact this had on the city. Other historians on the project address this topic differently: with a focus on migration, for example, or on the persistence of the Italian minority.

3) This is a research project, but there is also an explicit interest in dissemination and working with communities. How do you think it is possible to take the work of historians out of academia and build a fruitful interaction with the public?

This is a really important question, and it goes beyond resorting to the usual strategies of giving talks and writing for a more general audience. For us, it is a research question: how can new technologies allow us to tell stories differently – more effectively, but also generating new insights that wouldn’t be possible with the usual methods? Maps allow us to incorporate the spatial dimension into history, something we already explored in the first phase of the project. We also continue to seek ways to involve “citizen scientists” in the development of this map – in our case, citizen-scientists would be elders who have personal stories to share, and amateur historians who have collected valuable information. With this new mobile-phone based project, we are looking at ways that augmented reality can be harnessed to help bring the history of sites in the city to life in an easy-to-access format.

To Top

To Top