Cyber attacks are growing in the European Union

The pandemic, which moved citizen’s lives into the digital sphere, saw a rise in security breaches within European businesses and institutions. Cyber attacks against key European sectors doubled in 2020. Although Brussels is working to plug the gaps, the invasion of Ukraine threatens to intensify the cyber war

Cyber-attacks-are-growing-in-the-European-Union

On 14th May 2021, Donna-Marie Cullen was waiting for her radiotherapy appointment as part of her battle against an aggressive brain tumour, when she received an unexpected call : a cyber attack had brought down the IT network of the Irish health service and her treatment had to be temporarily suspended.

After an intense year of pressure as a result of the pandemic, the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) had succumbed, not to the virus nor to the chaos that ensued with lockdowns, but as a result of an invisible aggression being carried out hundreds of kilometres away.

Subsequent investigations concluded that the cause had been a ransomware attack perpetrated by Wizard Spider , a cybercriminal group based in Saint Petersburg who were demanding 14 million pounds – around 17 million euros – in return for calling off the attack. The Irish authorities chose to fight back, a decision which resulted in the suspension of thousands of appointments, a return to pen and paper records for months, the leaking of confidential medical records of 520 patients, and a financial loss of approximately 100 million euros .

Far from being an isolated case, the aggression suffered by HSE stands out among the avalanche of cyberattacks that had as its goal key institutions and businesses in the European Union. The shadow of Russia has always loomed over Europe’s digital world, but the pandemic has increased the frequency and virulency of attacks.

Unsurprisingly, in 2020, significant malicious attacks against key sectors doubled in Europe – up to 304 incidents compared to 146 in 2019 – according to the European Union’s Cybersecurity Agency (Enisa). Cyber attacks on hospitals and healthcare networks rose by 47%.

The new normal provides rich pickings for cyber criminals

Day by day, as cases rose and the pandemic ravaged Europe, the lives of its citizens gradually moved online. Suddenly, remote working, internet shopping and socialising through a screen became the norm. Although digital solutions meant that the world did not completely collapse, thanks to years of innovation, it also presented a pot of gold to cyber criminals.

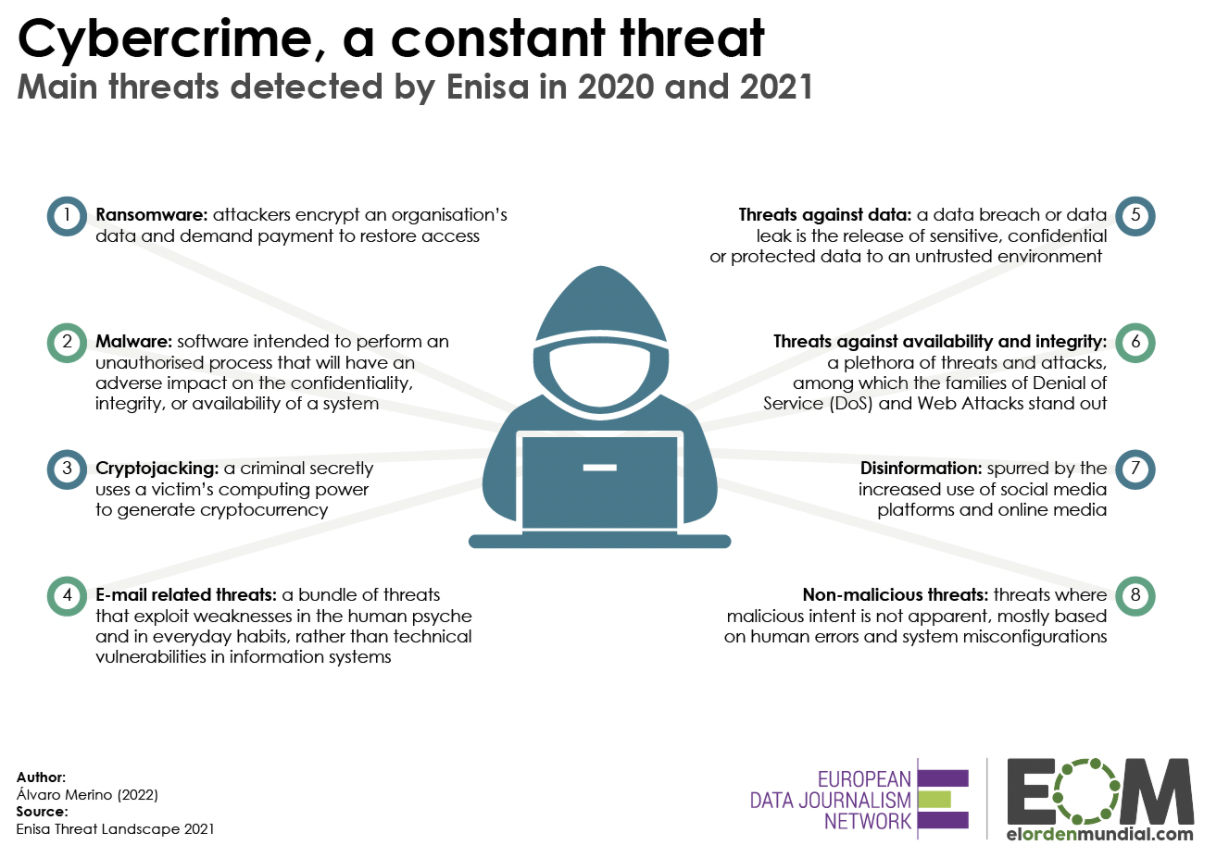

On top of Covid-19, the transition from traditional infrastructure to the web, growing interconnectivity and the appearance of new technologies such as artificial intelligence has provoked a growth in cyber attacks “with regard to sophistication, complexity and impact”, according to Enisa. In its 2021 report , Enisa warned that “this trend [of accelerated digital transformation] has raised the risk of attacks and, as a result, the number of cyber attacks directed at businesses and other organisations has increased”.

works became priority targets for cybercriminal groups at the beginning of the pandemic. Another target in the healthcare sector that suffered a paralysing cyber attack was the University Hospital of Brno , Czechia, which in March 2020 was forced to shut its IT networks, causing a delay in urgent operations and relocations of severely ill patients. Even the European Union’s own institutions suffered a cyber attack in March of 2021 , though apparently without a security breach.

Russia, the constant threat

The anonymous nature of these aggressions often makes it difficult to identify the enemy and respond proportionally. It is even harder in the case of supposedly non-state actors who are shielded by those who condemn them in public.

Although this makes it hard to establish the precise cyber capacity of each country, it is clear that Russia is one of the most prolific actors in the international sphere. Moscow uses the cyberspace to act on its geopolitical aspirations: reinforcing its role as a global power, consolidating control of its ‘sphere of influence’, and disrupting organisations that it deems to be an enemy, such as the EU or NATO.

There are dozens of examples: Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark have identified themselves in recent years as being victims of Russian cyber espionage; France announced at the beginning of 2021 that several of its key businesses, including Airbus and Orange, had been compromised by hacker attacks linked to Russia; last September, Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, accused Moscow of attempting to hack into the computers of several European politicians and journalists, as well as leading figures in the energy sector and other citizens with a certain social relevance.

Apart from accessing sensitive information, Russian cyber criminals look to extract the personal data of European citizens in order to blackmail them or thwart European data protection systems, highlighting the vulnerability of the European digital society. The problem for investigators lies in the fact that it is hard to trace these attacks back to the Kremlin, because, in the majority of cases, the accusations are based on indicators, rather than on evidence strong enough to demand an explanation from Russia.

The reaction in Brussels

The European Commission and Member States are perfectly aware that they are now central targets for cyber attacks, and that if Moscow keeps operating unimpeded in European networks there will be more security breaches.

To protect its networks, the European Commission updated its Cybersecurity Strategy in December 2020 and introduced a new directive concerning a tighter common level of cybersecurity in the Union (Directive NIS2). Both measures aim to strengthen its capacity to repel cyber attacks and extend network protection to new sectors, as well as support greater investments in cybersecurity for European organisations, which are currently 41% less than in the United States .

On top of that, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has further alerted the European Union: the European Central Bank has asked its national central banks to prepare to counter Russian cyber attacks, and the French Presidency of the European Council has promoted training drills to prepare for large scale attacks on supply chains in Member States.

All of this proves one thing: cyber wars are no longer science fiction stuff, they are already in full swing. Although they might not spill blood, they can have a crippling effect on the daily lives of citizens. With raised swords – or, rather, computers – and Russia that together with digital transformation pose enormous threats, the European Union is ready for battle, bringing the world with it to make cyberspace a safer environment for all.

This article is published in collaboration with the European Data Journalism Network and it is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Tag: EDJNet

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Cyber attacks are growing in the European Union

The pandemic, which moved citizen’s lives into the digital sphere, saw a rise in security breaches within European businesses and institutions. Cyber attacks against key European sectors doubled in 2020. Although Brussels is working to plug the gaps, the invasion of Ukraine threatens to intensify the cyber war

Cyber-attacks-are-growing-in-the-European-Union

On 14th May 2021, Donna-Marie Cullen was waiting for her radiotherapy appointment as part of her battle against an aggressive brain tumour, when she received an unexpected call : a cyber attack had brought down the IT network of the Irish health service and her treatment had to be temporarily suspended.

After an intense year of pressure as a result of the pandemic, the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) had succumbed, not to the virus nor to the chaos that ensued with lockdowns, but as a result of an invisible aggression being carried out hundreds of kilometres away.

Subsequent investigations concluded that the cause had been a ransomware attack perpetrated by Wizard Spider , a cybercriminal group based in Saint Petersburg who were demanding 14 million pounds – around 17 million euros – in return for calling off the attack. The Irish authorities chose to fight back, a decision which resulted in the suspension of thousands of appointments, a return to pen and paper records for months, the leaking of confidential medical records of 520 patients, and a financial loss of approximately 100 million euros .

Far from being an isolated case, the aggression suffered by HSE stands out among the avalanche of cyberattacks that had as its goal key institutions and businesses in the European Union. The shadow of Russia has always loomed over Europe’s digital world, but the pandemic has increased the frequency and virulency of attacks.

Unsurprisingly, in 2020, significant malicious attacks against key sectors doubled in Europe – up to 304 incidents compared to 146 in 2019 – according to the European Union’s Cybersecurity Agency (Enisa). Cyber attacks on hospitals and healthcare networks rose by 47%.

The new normal provides rich pickings for cyber criminals

Day by day, as cases rose and the pandemic ravaged Europe, the lives of its citizens gradually moved online. Suddenly, remote working, internet shopping and socialising through a screen became the norm. Although digital solutions meant that the world did not completely collapse, thanks to years of innovation, it also presented a pot of gold to cyber criminals.

On top of Covid-19, the transition from traditional infrastructure to the web, growing interconnectivity and the appearance of new technologies such as artificial intelligence has provoked a growth in cyber attacks “with regard to sophistication, complexity and impact”, according to Enisa. In its 2021 report , Enisa warned that “this trend [of accelerated digital transformation] has raised the risk of attacks and, as a result, the number of cyber attacks directed at businesses and other organisations has increased”.

works became priority targets for cybercriminal groups at the beginning of the pandemic. Another target in the healthcare sector that suffered a paralysing cyber attack was the University Hospital of Brno , Czechia, which in March 2020 was forced to shut its IT networks, causing a delay in urgent operations and relocations of severely ill patients. Even the European Union’s own institutions suffered a cyber attack in March of 2021 , though apparently without a security breach.

Russia, the constant threat

The anonymous nature of these aggressions often makes it difficult to identify the enemy and respond proportionally. It is even harder in the case of supposedly non-state actors who are shielded by those who condemn them in public.

Although this makes it hard to establish the precise cyber capacity of each country, it is clear that Russia is one of the most prolific actors in the international sphere. Moscow uses the cyberspace to act on its geopolitical aspirations: reinforcing its role as a global power, consolidating control of its ‘sphere of influence’, and disrupting organisations that it deems to be an enemy, such as the EU or NATO.

There are dozens of examples: Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark have identified themselves in recent years as being victims of Russian cyber espionage; France announced at the beginning of 2021 that several of its key businesses, including Airbus and Orange, had been compromised by hacker attacks linked to Russia; last September, Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, accused Moscow of attempting to hack into the computers of several European politicians and journalists, as well as leading figures in the energy sector and other citizens with a certain social relevance.

Apart from accessing sensitive information, Russian cyber criminals look to extract the personal data of European citizens in order to blackmail them or thwart European data protection systems, highlighting the vulnerability of the European digital society. The problem for investigators lies in the fact that it is hard to trace these attacks back to the Kremlin, because, in the majority of cases, the accusations are based on indicators, rather than on evidence strong enough to demand an explanation from Russia.

The reaction in Brussels

The European Commission and Member States are perfectly aware that they are now central targets for cyber attacks, and that if Moscow keeps operating unimpeded in European networks there will be more security breaches.

To protect its networks, the European Commission updated its Cybersecurity Strategy in December 2020 and introduced a new directive concerning a tighter common level of cybersecurity in the Union (Directive NIS2). Both measures aim to strengthen its capacity to repel cyber attacks and extend network protection to new sectors, as well as support greater investments in cybersecurity for European organisations, which are currently 41% less than in the United States .

On top of that, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has further alerted the European Union: the European Central Bank has asked its national central banks to prepare to counter Russian cyber attacks, and the French Presidency of the European Council has promoted training drills to prepare for large scale attacks on supply chains in Member States.

All of this proves one thing: cyber wars are no longer science fiction stuff, they are already in full swing. Although they might not spill blood, they can have a crippling effect on the daily lives of citizens. With raised swords – or, rather, computers – and Russia that together with digital transformation pose enormous threats, the European Union is ready for battle, bringing the world with it to make cyberspace a safer environment for all.

This article is published in collaboration with the European Data Journalism Network and it is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Tag: EDJNet