Photo by Justin Lim on Unsplash

Online advertising is based on the collection and sharing of user data, a system which rests mostly in a few powerful hands, including Google. Privacy and data protection are at issue, and Europe is debating what action should be taken

“We asked the Commission to consider the gradual elimination of targeted advertising, if not a total ban across the European Union”. These were the words of Alex Agius Saliba , Maltese MEP, back at the beginning of October. The same request is found in a recommendation document voted unanimously by the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs and written by German MEP Tiemo Wölken.

What it is, how it works, and why it’s a problem

What people are talking about above is targeted advertising — where internet users and the data linked to their profile become the centre of focus for advertisers. Up to the early 2000s online advertising was based on context . Algorithms analysed the content of visited pages, then decided which ads should be shown in specific spaces. Ad content was based on the nature of the web space, not those who visit. For example: reading an article on skiing season, you see ads for mountain resorts or winter clothing brands.

Targeted advertising, on the other hand, is a more complex system, and aims to display the ads most pertinent to the user profile currently viewing the page. Currently the most sophisticated and widespread system is automated bidding. While the page is loading, an identifier linking the user to their online (and sometimes even offline) activity is sent to a series of agencies which compete for the user’s attention in an automated market. This is all accomplished in fractions of a second, without the user noticing anything. The breakthrough that led to this system’s widespread adoption can be traced back to 2007, when Google acquired DoubleClick , a company whose success was built on just such a system, and on a large network of advertisers, publishers and ad agencies.

According to a report published in 2018 by Johnny Ryan, working for Brave browser at the time, real-time bidding (RTB) allows the following, among other things, to be shared: what the user is looking at or reading, their geographical position, IP address, description of the application. Depending on the RTB system being used, other identifying data can be retrieved, such as income bracket, age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, religion, political views, social media influence, etc.

From the perspective of companies using RTBs, Google included, it’s a service that guarantees maximum efficiency for both advertiser and user: the former rests assured that their ad will be seen by interested users; and the latter will see ads that are more relevant to their needs and spending habits. The promise to editors is a major enhancement of their ad space. Targeted ads should increase clicks and even some “conversions”, namely installing an app. The more relevant an ad, the more users will click, which increases the value of the ad space.

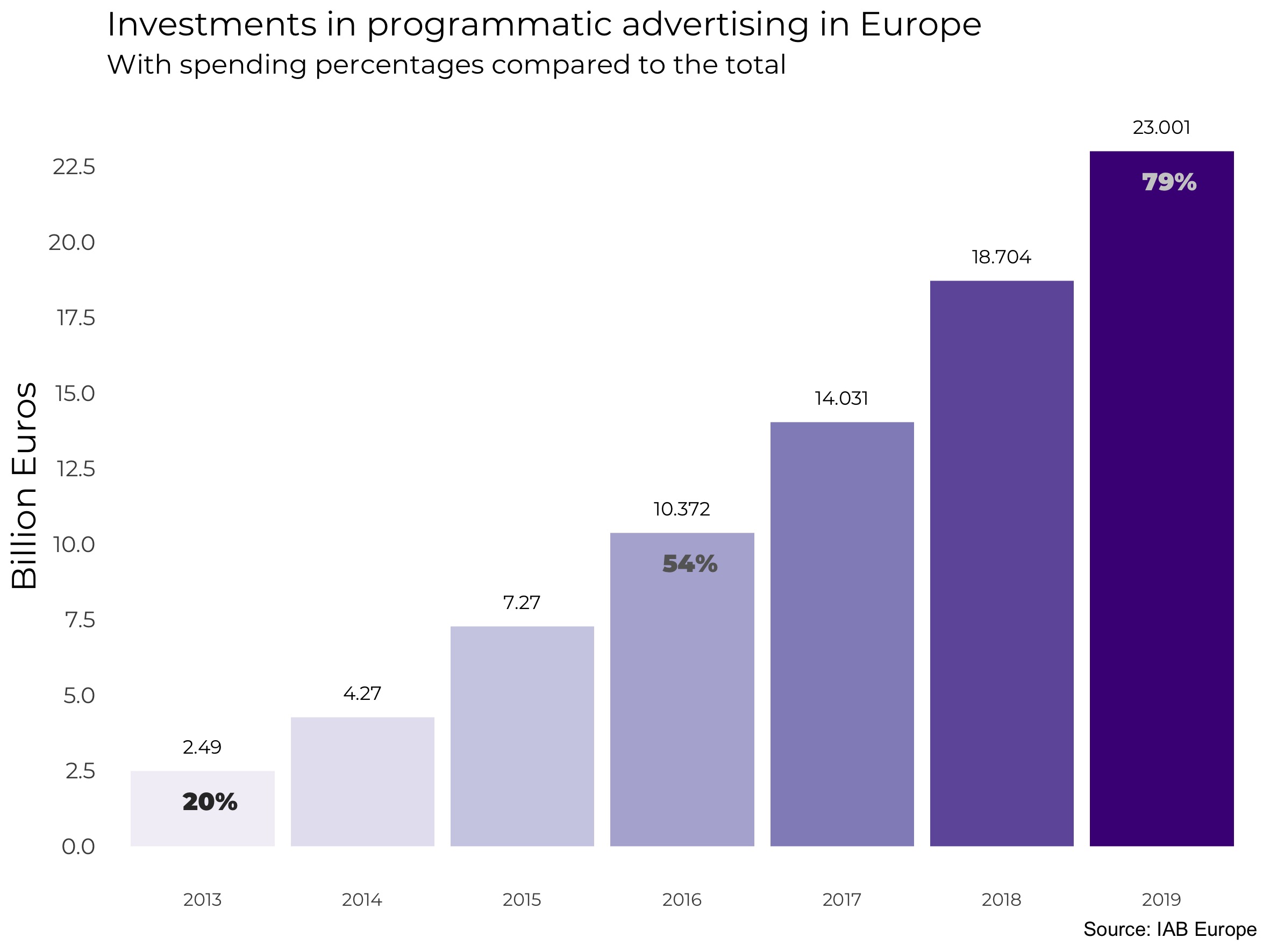

Source: IAB Europe

Excessive market concentration

Targeted ads are founded on two elements: the development of platforms with ever more sophisticated profiling and bidding management abilities, and the collection of user data. The former favours market concentration because, as happens all too often in the high-tech sector, it’s the more powerful companies with the resources to develop the platforms. And when they’re not the first, they can easily acquire any companies that happen to be especially innovative.

According to a report by the independent PLUM agency concerning the UK , “Google and Facebook and, to a lesser extent, Amazon (GFA) have a unique scale and breadth of activity in the online advertising market, complemented by businesses in adjacent markets. In particular, GFA are distinguished by a large scale of owned advertising inventory, well-developed advertising technology platforms(particularly Google), technologies in adjacent markets (such as Google Chrome and Android), and extensive proprietary data.They operate data ‘walled gardens’ collecting user data from various sources but sharing only aggregated data with partners”. According to the same report, Google is a leader in the UK, in this intermediate development phase, accounting for 30-50 percent of the supply and 22-35 of the demand, while 80-90 percent of publishers and advertisers use its services.

Running practically the whole supply chain, conflicts of interest have emerged and, according to information gathered by PLUM, ads managed by Google have in the past been given preference in the automated bids, to the disadvantage of other advertisers. It would seem such practices have now stopped. On October 28 the Italian Competition Authority expressed its concerns: “In the crucial market of online advertising, which Google controls thanks to its dominant position in a large portion the digital sector, the Authority would like to contest their unfair use of the enormous quantity of data collected by their own applications, preventing competing online advertisers to compete effectively”.

The problem with privacy and data protection

At present, at least 22 digital rights organisations have presented cases to a range of European data protection authorities. The first to raise the question publicly, in 2018, were Johnny Ryan and the Open Rights Group. At the start of 2019, the Polish organisation Panoptykon presented a similar case to the Warsaw authority against Google and Interactive Advertising Bureau Europe (IAB), claiming that their protocols, which determine the categories used in data collection, violate a number of principles contained in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). IAB Europe responded to the accusations claiming that, if their protocol does indeed allow them to collect such data, companies that use this protocol are still bound to respect data protection laws — and it is this, rather than the protocol, that needs investigation.

Toward the close of September 2020, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL), with which Johnny Ryan is now collaborating, published further details on the risks and consequences of the ongoing and massive collection of personal data. User profiling can also be used for operations that go beyond advertising, or try to reach users by exploiting sensitive categories. For example, the

data broker [1] OnAudience, headquartered in Poland, used profile data of 1.4 million people , collected across targeted advertising platforms, to spread a political message to people open to LGBTQ+ issues. Even apparently anonymous users are linked to a unique identifying code. This and other advertising modules created by OnAudience are available through automated bidding platforms owned by Google and others, and the same profile database can be used to display other kinds of ads. The ICCL has shown that through Google’s protocol 1200 people in Ireland were profiled under categories such as “substance abuse”, “diabetic”, “chronic pain”, and “sleep disturbance”. With IAB’s protocol, still in Ireland, a data broker was able to profile 1300 people as “AIDS and HIV”, “supports incest and rape”, “brain tumour”, “incontinence” and “depression”.

Mobilewalla has claimed much greater numbers. In Europe alone they have apparently collected data on the geolocation of 117 million devices , from a total of 61 billion observations per month. According to founder and CEO Anindya Datta , a two year archive of geolocation data is enough to map individual behavioural patterns. For example, you could establish who regularly visits church and reach them with an ad when they get there.

Recently an investigation by the Belgian Data Protection Authority concluded that the Transparency and Consent Framework published by IAB (and a standard in the sector) violates numerous GDPR principles, including transparency, accuracy, responsibility and the legality of transmitting data. According to the ICCL, article 5(f) on data security plays a major role here, since it’s impossible to know where data will end up once collected. The latest legal development concerns the Open Rights Group, which took the English Data Protection Authority to court after the latter decided to close its investigation on digital advertising last September, despite its own recommendations not being adapted by operators in the sector, and after having already established in 2019 that targeted advertising operates in violation of GDPR.

We approached Paul De Hert, a leading European expert on the relationship between privacy and technology, and Alessandro Ortalda, researcher at the University of Brussels. Both confirm the eternal battle between online advertising and data protection, especially when it comes to transparency. This means both the data provided and the way in which it is displayed. “In the context of online surfing, where users jump quickly from content to content, it is complex for data controllers to craft privacy policies and consent collection forms that catch the attention of the data subjects, who are usually keen to accept hastily everything that pops up on the screen and to move straight to the content they are seeking. This seriously impairs the effectiveness of the information sharing and might make the consent provided by data subjects invalid, as it might fail to reach the threshold of ‘informed consent”.

Doubts surrounding the system’s real effectiveness

The digital industry umbrella organisation Digital Content Next, which has among its members some of the major international media outlets, declared in 2019 that even if targeted advertising had to disappear, “the sky wouldn’t fall”. In January 2020 the Netherlands national public television station NPO claimed to have removed every system capable of tracing users from their webpages, choosing to sell their ad space only on a contextual basis. According to data shared by NPO and published by Brave , the network’s advertising revenue increased by 62 and 79 percent respectively in the first two months of the year. From March, the pandemic decidedly slowed the pace, but the trend has not reversed. It has to be asked if advertising based on automated bidding really offers advantages for market actors, except those who manage the platform.

According to US researcher Tim Hwang, there is a large bubble forming in the online advertising sector. Currently there’s still broad belief in the fact that “something so complex can’t not work”, but it may soon be all too clear that this system does not produce much additional value. In his recent book “Subprime Attention Crisis” , Hwang explains that the main problem with measuring the system’s effectiveness is that those who publish the data are also those who offer the services: “Entities like the Interactive Advertising Bureau and the Association of National Advertisers are major outlets for research on the state of the marketplace, but they simultaneously serve as advocacy organizations on behalf of the industry. The space lacks a robust, independent institution to act as a counterweight, to objectively investigate industry claims and conduct ongoing experimentation to test the health of the marketplace”.

There is another effectiveness problem which in fact precedes the introduction of automated bids. The click rate on ads served by Google’s AdWords is 0.46 percent — less than one person in 200; moreover, it appears that up to half of smartphone taps are due to people accidentally clicking or tapping. Another thing that influences the accuracy of results is the fact that many of these ads are never really seen by the user: while the automated bidding system may very precisely determine which ads to show and in which spaces to show them, these ads may load at the bottom of the page or in another less visible area. Visibility is a familiar problem, as a 2014 Google report shows. The report suggests that 56.1 percent of ads served online have never been viewed by a human. As far as we know, the industry has managed to convince advertisers and publishers that their system is indispensable: a system which endangers core principles of privacy and data protection.

[1] Data brokers are companies which collect data, or acquire it from other companies, and aggregate this data. The aim of some data brokers is to offer “profile packets” for resale to other companies; for example, those interested in targeted advertising.

This article was produced as part of the Panelfit project, co-financed by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme (grant agreement n. 788039). The Commission has not participated in the preparation of this text and is not responsible for its content. The article is part of the independent journalism outlet, EDJNet .