The slogans of ’89 have been appropriated by neonazis

OBCT is among the founders of ECPMF, a media freedom centre based in Leipzig – just where the demonstrations that would lead to the collapse of the Wall started in October 1989. Thirty years later, one of the slogans of that revolutionary autumn has become an angry claim on the electoral posters of the far-right AfD party

The-slogans-of-89-have-been-appropriated-by-neonazis

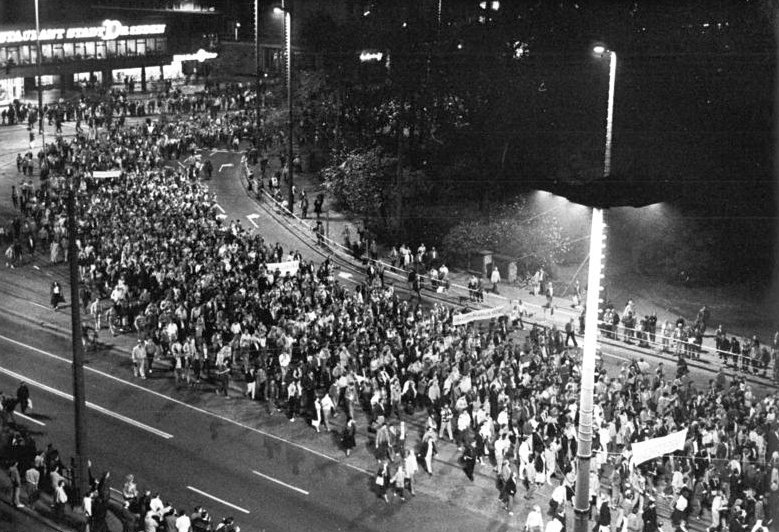

Monday demonstrations in Leipzig in 1989 (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1989-1023-022/Friedrich Gahlbeck /CC-BY-SA 3.0 )

"Wir sind das Volk", we are the people. In early October 1989, while the GDR, the German Democratic Republic, was on the verge of financial collapse and the stability of the Warsaw Pact countries was threatened both by the reforms in the Soviet Union and by the movements from below across the block, in East Germany internal dissent became an increasingly explicit protest. The leadership, however, insisted on repressing every little hint. All it would take was a sign, a joke, an unauthorised walk, and police stations and prisons would be filled with thousands and thousands of "protesters", "agitators", "people who despise and offend their homeland". They were non-aligned youths, environmentalists, members of grassroots evangelical groups, punks and objectors, who for almost a decade, supported by some Protestant pastors, had been fuelling the invisible revolt that would lead to the so-called "peaceful revolution". A street revolution, under the slogan "Wir sind das Volk".

Shouted in front of the Vopos, the Volkspolizisten who created a cordon around the people assembled in St. Nicholas Square every Monday, at the beginning of October 1989 this slogan became a formula of collective protection, the pacifist command of the demonstration’s security. On October 9th, for the first time in forty years, it worked. For the first time, despite the 70,000 people walking the avenues of the Ring, despite the screams and chants, for the first time the police stood and watched.

"I shudder even now when I think of it", Martin Jankowski told me ten years ago, when the stories of dissent in the GDR and the autumn of 1989 became the theme of a book published for the twentieth anniversary of the Wall’s collapse. "There was talk of hundreds of black bags ready to contain the bodies, and some of the officials had proposed a Chinese solution, obviously referring to what we all remembered very well, namely the massacre of Piazza Tienanmen a few months earlier", recalled Martin, a musician who in the 1980s participated in clandestine gatherings of dissidents in the church of San Nicola, meetings disguised as prayer celebrations.

However, the day after the great demonstration in Leipzig, the prisons did not fill with dissidents. Instead, the rooms of power opened to dialogue, party leader Erich Honecker resigned, and on October 18th successor Egon Krenz announced "the turning point" (die Wende), with the development of measures that would open up the possibility of travelling abroad without restrictions. Until the clumsy announcement of November 9th, broadcast live on TV as indeed were all the press conferences of the regime.

A month earlier, on October 9th, 1989, pastor Christoph Wonneberger, the inventor of the so-called "prayers for peace" that had been held in Dresden and then in Leipzig for years, was supervising the demonstration on bicycle. "Already in the early 1980s we thought of prayers for peace as a national network that would allow us to exchange information and keep in touch, bypassing the bans by the state and the ecclesiastical authorities", he told me ten years ago, when the slogan "Wir sind das Volk" and the Monday demonstrations were still the exclusive memory of Leipzig’s "peaceful revolution". Five years later, in 2014, it was first appropriated by the extreme right-wing movement Pegida (European patriots against the Islamisation of the West), a regularly registered association which since autumn 2014 has organised in Dresden, just every Monday, demonstrations with several hundred people to denounce the alleged Islamisation of Europe and challenge Germany’s migration policies.

The reversal is complete and lexical manipulations abound, with the contribution of the irony that has always been politically very active in Germany: on the one hand, the demands for democracy and the initiatives for disarmament, for dialogue, against pollution by Wonneberger, awarded in 2014 with the Leipzig Media Foundation’s Prize for freedom and the future of the media ; on the other hand, 25 years later, the anti-European and anti-Islam slogans by the extremists of Lutz Bachmann, repeatedly investigated for instigating racial hatred. A few days ago, on the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the regime, Dresden’s municipal council approved by majority (39-29) a motion by Max Aschenbach of the satirical party Die Partei (The Party), declaring a – far from satirical – "Nazi emergency" (Nazinotstand).

The complexity of the political scenario is exacerbated by the suggestions of a linguistic memory crumbled in 40 years of division between the two Germanies – 40 years during which even language, like almost everything else, took on different connotations – and exhumed in the almost 30 years of – in many respects, botched – reunification. With the Nazi forces never effectively neutered (some naziskin groups existed in East Germany too, but the regime’s press simply did not register their presence), and the economic hardship that fosters anti-European, but primarily anti-West Germany claims, East Germany’s current scenario is the proof that the revolutionary ferment of the autumn of 1989 died out too quickly. Those late October’s dialogues between grassroots movements and the regime were too quickly silenced in favour of the "turning point" – the international financial aid, the equalisation of the two currencies, the reconversion of industries, the occupation of the universities. Not even Helmut Kohl, the Bonn chancellor whose party was the winner in the East (March 1990) even before the reunification (October 3rd, 1990), initially wanted a united Germany; but his idea of confederation had to oblige the US push for a single Germany, a reliable member of NATO.

Nobody went for subtle, this is the impression of many. And this was also the impression of Christian Führer, pastor of St. Nicholas at the time of the Monday demonstrations in Leipzig, interviewed ten years ago for the Sunday supplement of Sole 24 Ore: “Just think of November 9th, the tragic day of the pogrom of 1938, fifteen years after Hitler’s failed putsch of 1923 ("Putsch of Munich"), a day that in that same 20th century also corresponds to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Of course, as we now know, it was a fatality, a twist of fate. It could have happened five days before, it could have happened five days later. But the fact that it happened precisely on November 9th still creates a lot of embarrassment, and the official celebrations of that day, every year, always have an unpleasant aftertaste: we celebrate the fall of the regime of socialist Germany, the rediscovered freedom of a people, but at the same time we commemorate the thousands of victims of the "Night of the Crystals", and we apologise to the world for Germany’ responsibility in the extermination of the Jews. That is why this date is so overloaded with meanings, and I much prefer October 9th. A month before the collapse of the Wall, a month before the world-wide party that would lead to the reunification of Germany; with its epicentre in Leipzig and not in Berlin”.

And just when the memory of that November 9th, 1938 seemed to be buried by the rhetoric of the celebrations of November 9th, 1989, Germany is struggling again with the embarrassment for the Nazi-populist impulses; with the slogan "Wir sind das Volk" on the election posters of AfD, Alliance for Germany; with the city of Dresden officially declaring its "Nazi emergency". The rush to archive history, perhaps, always comes with a price.

*Paola Rosà is author of the book "Lipsia 1989. Nonviolenti contro il Muro", Il Margine

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

The slogans of ’89 have been appropriated by neonazis

OBCT is among the founders of ECPMF, a media freedom centre based in Leipzig – just where the demonstrations that would lead to the collapse of the Wall started in October 1989. Thirty years later, one of the slogans of that revolutionary autumn has become an angry claim on the electoral posters of the far-right AfD party

The-slogans-of-89-have-been-appropriated-by-neonazis

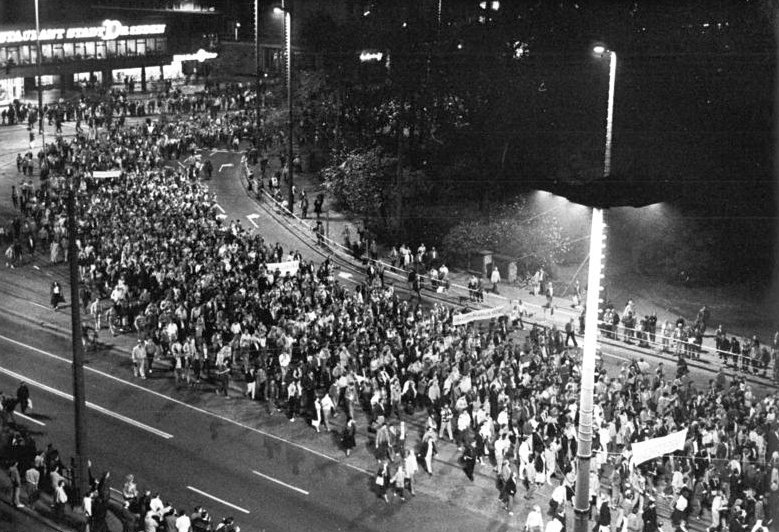

Monday demonstrations in Leipzig in 1989 (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1989-1023-022/Friedrich Gahlbeck /CC-BY-SA 3.0 )

"Wir sind das Volk", we are the people. In early October 1989, while the GDR, the German Democratic Republic, was on the verge of financial collapse and the stability of the Warsaw Pact countries was threatened both by the reforms in the Soviet Union and by the movements from below across the block, in East Germany internal dissent became an increasingly explicit protest. The leadership, however, insisted on repressing every little hint. All it would take was a sign, a joke, an unauthorised walk, and police stations and prisons would be filled with thousands and thousands of "protesters", "agitators", "people who despise and offend their homeland". They were non-aligned youths, environmentalists, members of grassroots evangelical groups, punks and objectors, who for almost a decade, supported by some Protestant pastors, had been fuelling the invisible revolt that would lead to the so-called "peaceful revolution". A street revolution, under the slogan "Wir sind das Volk".

Shouted in front of the Vopos, the Volkspolizisten who created a cordon around the people assembled in St. Nicholas Square every Monday, at the beginning of October 1989 this slogan became a formula of collective protection, the pacifist command of the demonstration’s security. On October 9th, for the first time in forty years, it worked. For the first time, despite the 70,000 people walking the avenues of the Ring, despite the screams and chants, for the first time the police stood and watched.

"I shudder even now when I think of it", Martin Jankowski told me ten years ago, when the stories of dissent in the GDR and the autumn of 1989 became the theme of a book published for the twentieth anniversary of the Wall’s collapse. "There was talk of hundreds of black bags ready to contain the bodies, and some of the officials had proposed a Chinese solution, obviously referring to what we all remembered very well, namely the massacre of Piazza Tienanmen a few months earlier", recalled Martin, a musician who in the 1980s participated in clandestine gatherings of dissidents in the church of San Nicola, meetings disguised as prayer celebrations.

However, the day after the great demonstration in Leipzig, the prisons did not fill with dissidents. Instead, the rooms of power opened to dialogue, party leader Erich Honecker resigned, and on October 18th successor Egon Krenz announced "the turning point" (die Wende), with the development of measures that would open up the possibility of travelling abroad without restrictions. Until the clumsy announcement of November 9th, broadcast live on TV as indeed were all the press conferences of the regime.

A month earlier, on October 9th, 1989, pastor Christoph Wonneberger, the inventor of the so-called "prayers for peace" that had been held in Dresden and then in Leipzig for years, was supervising the demonstration on bicycle. "Already in the early 1980s we thought of prayers for peace as a national network that would allow us to exchange information and keep in touch, bypassing the bans by the state and the ecclesiastical authorities", he told me ten years ago, when the slogan "Wir sind das Volk" and the Monday demonstrations were still the exclusive memory of Leipzig’s "peaceful revolution". Five years later, in 2014, it was first appropriated by the extreme right-wing movement Pegida (European patriots against the Islamisation of the West), a regularly registered association which since autumn 2014 has organised in Dresden, just every Monday, demonstrations with several hundred people to denounce the alleged Islamisation of Europe and challenge Germany’s migration policies.

The reversal is complete and lexical manipulations abound, with the contribution of the irony that has always been politically very active in Germany: on the one hand, the demands for democracy and the initiatives for disarmament, for dialogue, against pollution by Wonneberger, awarded in 2014 with the Leipzig Media Foundation’s Prize for freedom and the future of the media ; on the other hand, 25 years later, the anti-European and anti-Islam slogans by the extremists of Lutz Bachmann, repeatedly investigated for instigating racial hatred. A few days ago, on the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the regime, Dresden’s municipal council approved by majority (39-29) a motion by Max Aschenbach of the satirical party Die Partei (The Party), declaring a – far from satirical – "Nazi emergency" (Nazinotstand).

The complexity of the political scenario is exacerbated by the suggestions of a linguistic memory crumbled in 40 years of division between the two Germanies – 40 years during which even language, like almost everything else, took on different connotations – and exhumed in the almost 30 years of – in many respects, botched – reunification. With the Nazi forces never effectively neutered (some naziskin groups existed in East Germany too, but the regime’s press simply did not register their presence), and the economic hardship that fosters anti-European, but primarily anti-West Germany claims, East Germany’s current scenario is the proof that the revolutionary ferment of the autumn of 1989 died out too quickly. Those late October’s dialogues between grassroots movements and the regime were too quickly silenced in favour of the "turning point" – the international financial aid, the equalisation of the two currencies, the reconversion of industries, the occupation of the universities. Not even Helmut Kohl, the Bonn chancellor whose party was the winner in the East (March 1990) even before the reunification (October 3rd, 1990), initially wanted a united Germany; but his idea of confederation had to oblige the US push for a single Germany, a reliable member of NATO.

Nobody went for subtle, this is the impression of many. And this was also the impression of Christian Führer, pastor of St. Nicholas at the time of the Monday demonstrations in Leipzig, interviewed ten years ago for the Sunday supplement of Sole 24 Ore: “Just think of November 9th, the tragic day of the pogrom of 1938, fifteen years after Hitler’s failed putsch of 1923 ("Putsch of Munich"), a day that in that same 20th century also corresponds to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Of course, as we now know, it was a fatality, a twist of fate. It could have happened five days before, it could have happened five days later. But the fact that it happened precisely on November 9th still creates a lot of embarrassment, and the official celebrations of that day, every year, always have an unpleasant aftertaste: we celebrate the fall of the regime of socialist Germany, the rediscovered freedom of a people, but at the same time we commemorate the thousands of victims of the "Night of the Crystals", and we apologise to the world for Germany’ responsibility in the extermination of the Jews. That is why this date is so overloaded with meanings, and I much prefer October 9th. A month before the collapse of the Wall, a month before the world-wide party that would lead to the reunification of Germany; with its epicentre in Leipzig and not in Berlin”.

And just when the memory of that November 9th, 1938 seemed to be buried by the rhetoric of the celebrations of November 9th, 1989, Germany is struggling again with the embarrassment for the Nazi-populist impulses; with the slogan "Wir sind das Volk" on the election posters of AfD, Alliance for Germany; with the city of Dresden officially declaring its "Nazi emergency". The rush to archive history, perhaps, always comes with a price.

*Paola Rosà is author of the book "Lipsia 1989. Nonviolenti contro il Muro", Il Margine