Where do we stand on the road to a European Gigabit Society?

The road towards universally accessible ultra-fast connectivity in Europe still seems long and bumpy

Where-do-we-stand-on-the-road-to-a-European-Gigabit-Society

Image by TheAndrasBarta/Pixabay

About 20 percent of the European budget for 2021-2027 will be dedicated to the digital sector. As MEP Miapetra Kumpula-Natri, spokesperson for the Parliamentary Committee on Industry, Research and Energy, stated in late 2020 with respect to the European data strategy, "the pandemic has shown the importance of connectivity."

Kumpula-Natri explains that the EU is geared toward maintaining an approach based on using public funds to attract private investment, rather than directly funding initiatives by member states. "When the amount of data is doubling every year and a half or so, connectivity is the tool that creates and transfers data," she said. "If Europe’s industry does not adapt to next-generation connectivity, and if they are not willing to understand data as a reusable resource, we will not be able to reap the benefits of a well-functioning data economy.”

The connectivity goals the EU sets for itself in the Broadband Europe plan for 2025 are rather ambitious:

- Connections of at least 1 Gigabit per second (Gbps) for the main socio-economic drivers (schools, universities, transport hubs, airports, digital-intensive businesses, etc.)

- Uninterrupted 5G coverage for all urban areas and major terrestrial transport paths.

- Access to connectivity offering at least 100 Megabit per second (Mbps) for all European households.

In a recent communication to the European Parliament and other EU institutions, the Commission went so far as to set an objective of full gigabit coverage by 2030, through landlines, 5G and 6G (the latter is under development).

Even earlier, in 2010, the Digital Agenda for Europe set connectivity targets for 2020, which called for broadband coverage of at least 30 Mbps for all Europeans, and access to connections faster than 100 Mbps in at least half of all households. According to key indicators selected by the European Commission, next-generation network infrastructure (at least 30 Mbps) reached 85.8 percent of European households in 2019. Most countries are above this threshold, with only six countries falling below 80 percent: Bulgaria, Slovakia, Poland, Finland, Lithuania and France, which surprisingly comes in at 62.1 percent coverage.

Developing ultra-high capacity infrastructure

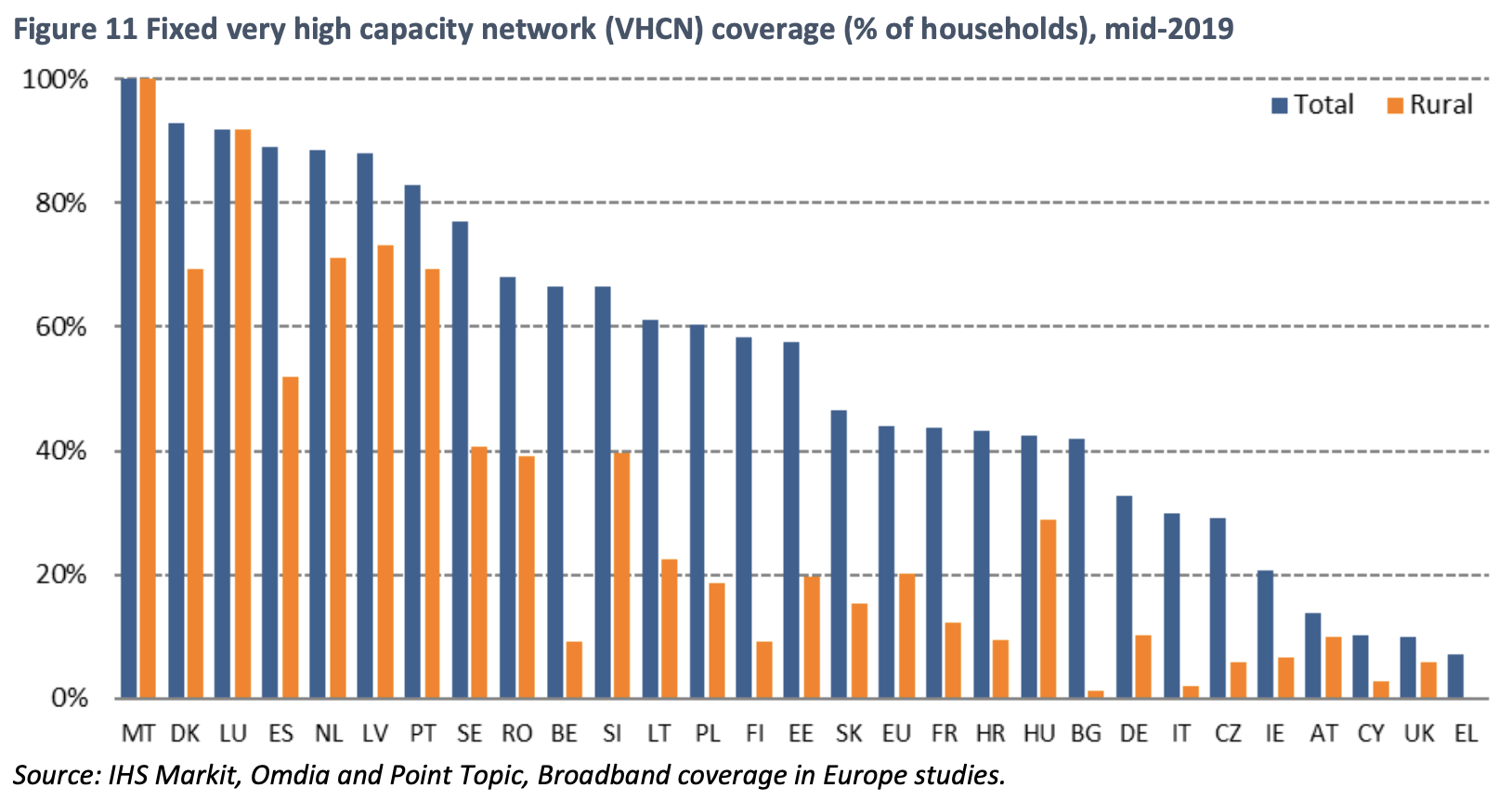

Compared to the Very High Capacity Network (VHCN), an infrastructure that includes fiber-optics and other technologies, and is needed to reach the goal of universal 1 Gbps by 2030, the European average coverage in 2019 (the latest available data) was 44 percent. Only two years earlier the average was 26 percent, meaning it increased by more than two-thirds. Behind these figures, however, lie large disparities, both between individual countries and between urban and rural areas

[1].

Source: The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI)

Many of the countries that stand out in terms of coverage have a relatively small land area. The first country of considerable size in the ranking is Spain, where 89 percent of all homes, and 51.9 percent of rural homes, have coverage. This is due to a series of investments by private companies, aided by the Programa de Extensión de la Banda Ancha de Nueva Generación, which provides €400 million in public funding (of which €300 million comes from the European Regional Development Fund, ERFD) between 2019 and 2022, to finance companies wishing to invest in infrastructure of at least 300 Mbps, scalable up to 1 Gbps.

Sticking with the same region, Portugal has 83 percent coverage overall, and 69.4 percent in rural areas. Here, major investments are underway to replace the submarine cables that connect Madeira and the Azores to the European mainland. A submarine cable linking Portugal to Brazil is also expected to come on line in 2021, a €150 million operation headed by EllaLink.

The performance of a highly advanced economy like that of Germany is striking. In 2019, the VHCN network covered only 3 in 10 homes nationwide, and only 1 in 10 in rural areas. Considering that in 2018 national coverage was only 9 percent, huge steps have clearly been taken in network development. Germany launched its "offensive" in 2016 to develop an ultra-high-capacity network (Eckpunkte Zukunftsoffensive Gigabit-Deutschland), which envisages public investments of €11 billion (with the aim of attracting much more with private initiatives) between 2017 and 2023, to achieve full coverage by 2025.

France also stands out in this regard. Nationally, coverage does not surpass the European average (43.8 percent), while in rural areas it is stationary (11.9 percent). The France Très Haut Débit national development plan, launched in 2013, aims to connect all homes in the country with a speed of at least 30 Mbps by 2022 and makes no mention of the goal of reaching 1 Gbps. The planned investment is about 20 billion euro, of which 3.3 billion is intended to cover the lack of private investment in some areas. Specifically, there is a great disparity in coverage between the most densely populated areas, where it reaches 90 percent, and less populated areas where coverage is around 60 percent, and falls as low as 11.9 percent in rural areas.

In Eastern Europe, Romania leads the way, with VHCN coverage in 68.1 percent of homes with VHCN lines, and 39.1 percent in rural areas. During the 2014-2020 funding period, the country allocated €100 million from the ERDF to connectivity development. Of this total, 45 million was invested in the RoNet project, which had the goal of reaching 721 locations with backhaul networks, which act as intermediaries in the signal passage between the central network and the local subnet. By the end of 2018, work had been planned in 607 locations and completed in 484.

According to the report just published by ETNO, an association bringing together the largest European telephone companies, European connectivity investments amounted to 51.7 billion euro in 2019, an increase of three billion over 2018. According to ETNO, the largest hurdle to development is the fragmentation of the European market, which consists of more than 40 companies, and the excessive level of regulation. In addition, according to the phone companies, the industry’s financial policies incentivize operators that compete by offering subscription plans that take advantage of existing networks, rather than pushing for the deployment of new, faster networks.

There is also a problem with the attractiveness of the sector, as Europe experiences lower network usage than other continents. Usage in Europe is 6.08 Gigabytes transferred per user per month, compared to 11.05 in the United States, and 9.29 in Japan. Companies searching for more cost-effective solutions are also behind the disparity between urban and rural areas. The private sector, according to the Digital Economy and Society Index Report 2020, leans heavily toward the former, more profitable areas, leaving the public sector to manage the less populated areas.

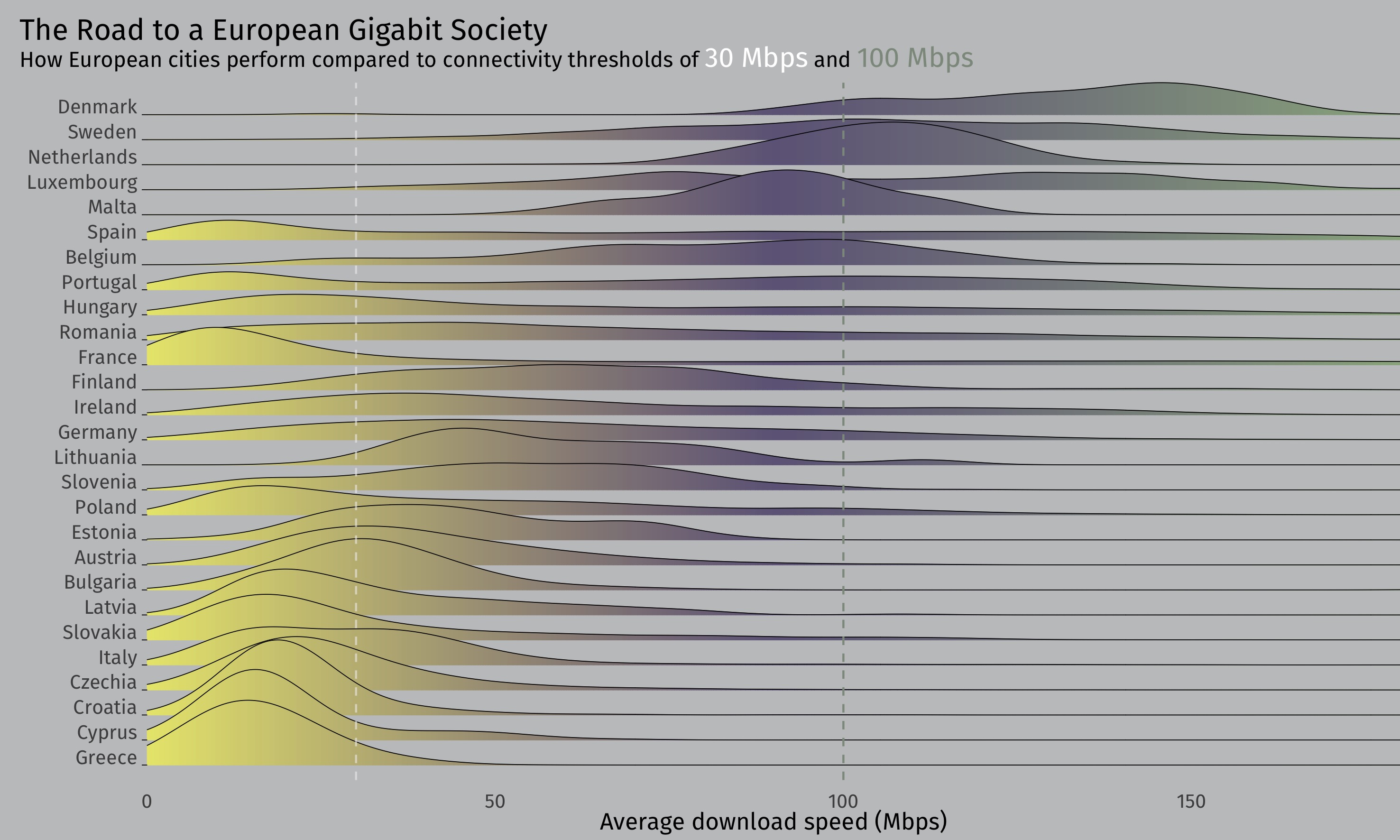

Thanks to data published by Ookla which compiles results from the Speedtest website, we can view the overall performance of connections across European countries.

Source: Ookla Open datasets

As can be seen, in several countries a significant percentage of cities have a connection slower than 30 Mbps

[2]. In France, Italy and Latvia this percentage is just over 50 percent. The Czech Republic and Slovakia reach 65.4 percent and 70.1 percent, respectively, with peaks coming close to complete coverage in Cyprus (85 percent), Croatia (89.2 percent) and Greece (93.2 percent).

The countries in which have substantially met the goal of at least 30 Mbps bandwidth nationwide are the Netherlands and Malta, where 100 percent has been reached, while just behind are Denmark, Sweden, Lithuania and Luxembourg, then Finland and Belgium. As for the other Digital Agenda goal (connectivity of at least 100 Mbps in all homes), the situation is quite similar. It should be said that the data does not specify whether the test was conducted in a home or elsewhere, for example a public office or school. Nevertheless, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden all surpass the 50 percent threshold, and Denmark stands out with over 91.9 percent of cities above the 100 Mbps threshold.

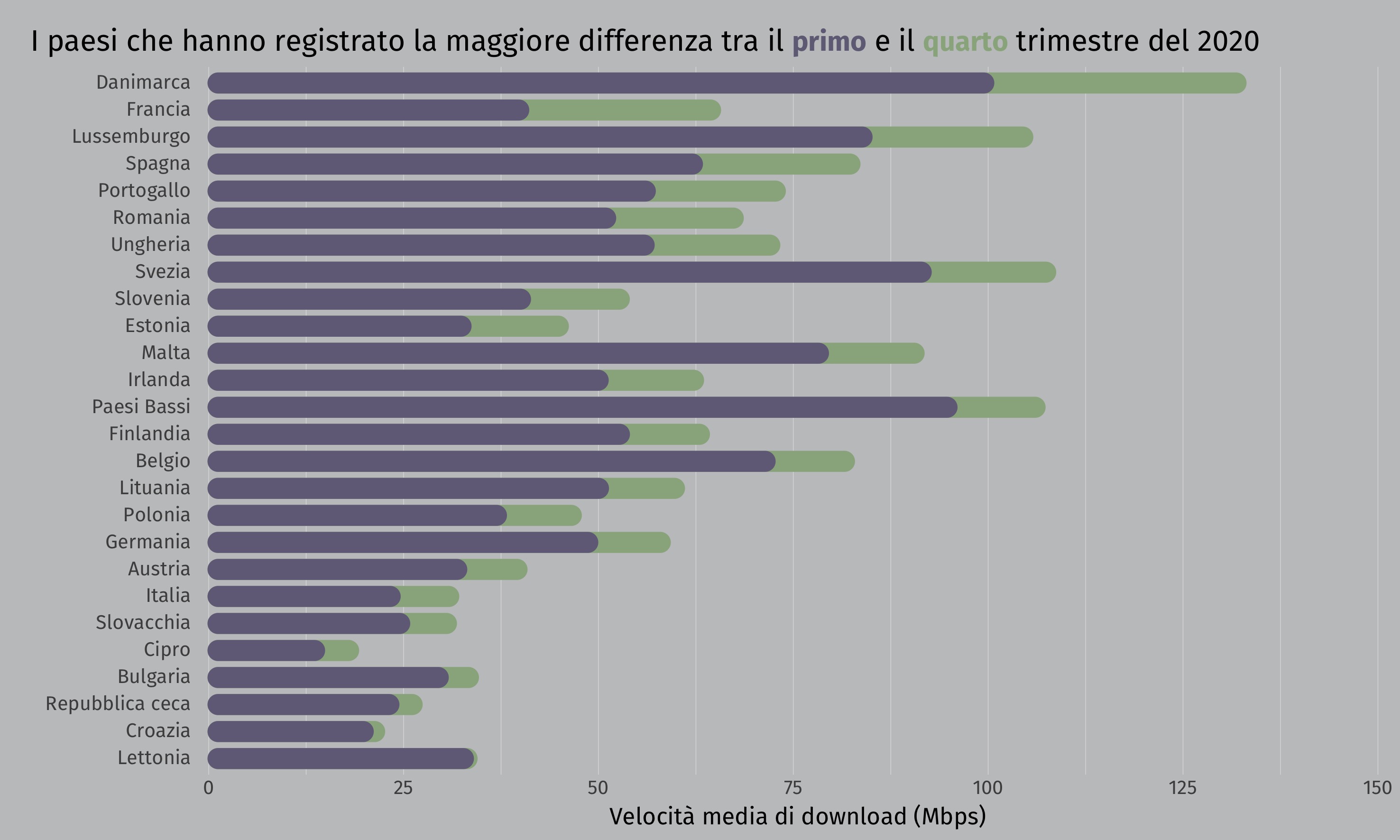

Comparing the data collected by Speedtest in Q1 and Q4 2020, we can see that all countries, albeit to varying degrees, experienced higher average download speeds in the latter part of the year. This may be due to a number of factors, from progress network development to the fact that many people during the pandemic have been forced to invest in a fast connection in order to work from home. Overall, the infrastructure seems to have held up to increased traffic and demand for high performance. Certain countries have economic incentives in place to encourage citizens. In late summer 2020, for example, the Italian government launched a "voucher plan" incentivizing households and businesses to sign up for contracts for at least 30 Mbps and up to 1 Gbps.

Source: Ookla Open datasets

The latest developments

The Council of the EU recently reached an agreement with the European Parliament, within the framework of the Connecting Europe Facility, to invest 2.06 billion euro in connectivity. The impact of this transition goes beyond purely technological considerations, and has direct repercussions on the lives of citizens — from health to the use of public services — and the issue of social inclusion. The European Commission has underlined the importance of digital technologies in favouring the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, and achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal. Energy transition is a complex issue, on which this technological transition will have a limited impact without essential, decisive policies on energy production.

[1] Rural areas are defined as those with less than 100 people per km2.

[2] We use landline download speed, which, although incomplete, is the most widely used reference measure in EU documents. To avoid having the more populous areas — where more speed tests are conducted — cause an imbalance in the data, when we refer to "average" we always mean the average speed weighted according to the number of tests conducted in each city.

Click here to explore data on internet speed across Europe, down to a municipal level, on an interactive dashboard.

This article is published in collaboration with the European Data Journalism Network and it is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Tag: EDJNet

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Where do we stand on the road to a European Gigabit Society?

The road towards universally accessible ultra-fast connectivity in Europe still seems long and bumpy

Where-do-we-stand-on-the-road-to-a-European-Gigabit-Society

Image by TheAndrasBarta/Pixabay

About 20 percent of the European budget for 2021-2027 will be dedicated to the digital sector. As MEP Miapetra Kumpula-Natri, spokesperson for the Parliamentary Committee on Industry, Research and Energy, stated in late 2020 with respect to the European data strategy, "the pandemic has shown the importance of connectivity."

Kumpula-Natri explains that the EU is geared toward maintaining an approach based on using public funds to attract private investment, rather than directly funding initiatives by member states. "When the amount of data is doubling every year and a half or so, connectivity is the tool that creates and transfers data," she said. "If Europe’s industry does not adapt to next-generation connectivity, and if they are not willing to understand data as a reusable resource, we will not be able to reap the benefits of a well-functioning data economy.”

The connectivity goals the EU sets for itself in the Broadband Europe plan for 2025 are rather ambitious:

- Connections of at least 1 Gigabit per second (Gbps) for the main socio-economic drivers (schools, universities, transport hubs, airports, digital-intensive businesses, etc.)

- Uninterrupted 5G coverage for all urban areas and major terrestrial transport paths.

- Access to connectivity offering at least 100 Megabit per second (Mbps) for all European households.

In a recent communication to the European Parliament and other EU institutions, the Commission went so far as to set an objective of full gigabit coverage by 2030, through landlines, 5G and 6G (the latter is under development).

Even earlier, in 2010, the Digital Agenda for Europe set connectivity targets for 2020, which called for broadband coverage of at least 30 Mbps for all Europeans, and access to connections faster than 100 Mbps in at least half of all households. According to key indicators selected by the European Commission, next-generation network infrastructure (at least 30 Mbps) reached 85.8 percent of European households in 2019. Most countries are above this threshold, with only six countries falling below 80 percent: Bulgaria, Slovakia, Poland, Finland, Lithuania and France, which surprisingly comes in at 62.1 percent coverage.

Developing ultra-high capacity infrastructure

Compared to the Very High Capacity Network (VHCN), an infrastructure that includes fiber-optics and other technologies, and is needed to reach the goal of universal 1 Gbps by 2030, the European average coverage in 2019 (the latest available data) was 44 percent. Only two years earlier the average was 26 percent, meaning it increased by more than two-thirds. Behind these figures, however, lie large disparities, both between individual countries and between urban and rural areas

[1].

Source: The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI)

Many of the countries that stand out in terms of coverage have a relatively small land area. The first country of considerable size in the ranking is Spain, where 89 percent of all homes, and 51.9 percent of rural homes, have coverage. This is due to a series of investments by private companies, aided by the Programa de Extensión de la Banda Ancha de Nueva Generación, which provides €400 million in public funding (of which €300 million comes from the European Regional Development Fund, ERFD) between 2019 and 2022, to finance companies wishing to invest in infrastructure of at least 300 Mbps, scalable up to 1 Gbps.

Sticking with the same region, Portugal has 83 percent coverage overall, and 69.4 percent in rural areas. Here, major investments are underway to replace the submarine cables that connect Madeira and the Azores to the European mainland. A submarine cable linking Portugal to Brazil is also expected to come on line in 2021, a €150 million operation headed by EllaLink.

The performance of a highly advanced economy like that of Germany is striking. In 2019, the VHCN network covered only 3 in 10 homes nationwide, and only 1 in 10 in rural areas. Considering that in 2018 national coverage was only 9 percent, huge steps have clearly been taken in network development. Germany launched its "offensive" in 2016 to develop an ultra-high-capacity network (Eckpunkte Zukunftsoffensive Gigabit-Deutschland), which envisages public investments of €11 billion (with the aim of attracting much more with private initiatives) between 2017 and 2023, to achieve full coverage by 2025.

France also stands out in this regard. Nationally, coverage does not surpass the European average (43.8 percent), while in rural areas it is stationary (11.9 percent). The France Très Haut Débit national development plan, launched in 2013, aims to connect all homes in the country with a speed of at least 30 Mbps by 2022 and makes no mention of the goal of reaching 1 Gbps. The planned investment is about 20 billion euro, of which 3.3 billion is intended to cover the lack of private investment in some areas. Specifically, there is a great disparity in coverage between the most densely populated areas, where it reaches 90 percent, and less populated areas where coverage is around 60 percent, and falls as low as 11.9 percent in rural areas.

In Eastern Europe, Romania leads the way, with VHCN coverage in 68.1 percent of homes with VHCN lines, and 39.1 percent in rural areas. During the 2014-2020 funding period, the country allocated €100 million from the ERDF to connectivity development. Of this total, 45 million was invested in the RoNet project, which had the goal of reaching 721 locations with backhaul networks, which act as intermediaries in the signal passage between the central network and the local subnet. By the end of 2018, work had been planned in 607 locations and completed in 484.

According to the report just published by ETNO, an association bringing together the largest European telephone companies, European connectivity investments amounted to 51.7 billion euro in 2019, an increase of three billion over 2018. According to ETNO, the largest hurdle to development is the fragmentation of the European market, which consists of more than 40 companies, and the excessive level of regulation. In addition, according to the phone companies, the industry’s financial policies incentivize operators that compete by offering subscription plans that take advantage of existing networks, rather than pushing for the deployment of new, faster networks.

There is also a problem with the attractiveness of the sector, as Europe experiences lower network usage than other continents. Usage in Europe is 6.08 Gigabytes transferred per user per month, compared to 11.05 in the United States, and 9.29 in Japan. Companies searching for more cost-effective solutions are also behind the disparity between urban and rural areas. The private sector, according to the Digital Economy and Society Index Report 2020, leans heavily toward the former, more profitable areas, leaving the public sector to manage the less populated areas.

Thanks to data published by Ookla which compiles results from the Speedtest website, we can view the overall performance of connections across European countries.

Source: Ookla Open datasets

As can be seen, in several countries a significant percentage of cities have a connection slower than 30 Mbps

[2]. In France, Italy and Latvia this percentage is just over 50 percent. The Czech Republic and Slovakia reach 65.4 percent and 70.1 percent, respectively, with peaks coming close to complete coverage in Cyprus (85 percent), Croatia (89.2 percent) and Greece (93.2 percent).

The countries in which have substantially met the goal of at least 30 Mbps bandwidth nationwide are the Netherlands and Malta, where 100 percent has been reached, while just behind are Denmark, Sweden, Lithuania and Luxembourg, then Finland and Belgium. As for the other Digital Agenda goal (connectivity of at least 100 Mbps in all homes), the situation is quite similar. It should be said that the data does not specify whether the test was conducted in a home or elsewhere, for example a public office or school. Nevertheless, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden all surpass the 50 percent threshold, and Denmark stands out with over 91.9 percent of cities above the 100 Mbps threshold.

Comparing the data collected by Speedtest in Q1 and Q4 2020, we can see that all countries, albeit to varying degrees, experienced higher average download speeds in the latter part of the year. This may be due to a number of factors, from progress network development to the fact that many people during the pandemic have been forced to invest in a fast connection in order to work from home. Overall, the infrastructure seems to have held up to increased traffic and demand for high performance. Certain countries have economic incentives in place to encourage citizens. In late summer 2020, for example, the Italian government launched a "voucher plan" incentivizing households and businesses to sign up for contracts for at least 30 Mbps and up to 1 Gbps.

Source: Ookla Open datasets

The latest developments

The Council of the EU recently reached an agreement with the European Parliament, within the framework of the Connecting Europe Facility, to invest 2.06 billion euro in connectivity. The impact of this transition goes beyond purely technological considerations, and has direct repercussions on the lives of citizens — from health to the use of public services — and the issue of social inclusion. The European Commission has underlined the importance of digital technologies in favouring the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, and achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal. Energy transition is a complex issue, on which this technological transition will have a limited impact without essential, decisive policies on energy production.

[1] Rural areas are defined as those with less than 100 people per km2.

[2] We use landline download speed, which, although incomplete, is the most widely used reference measure in EU documents. To avoid having the more populous areas — where more speed tests are conducted — cause an imbalance in the data, when we refer to "average" we always mean the average speed weighted according to the number of tests conducted in each city.

Click here to explore data on internet speed across Europe, down to a municipal level, on an interactive dashboard.

This article is published in collaboration with the European Data Journalism Network and it is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Tag: EDJNet