A motorised and electric scooter rider stop to chat at a crossroads during the COVID-19 state of emergency when most motorised transportation was prohibited in Tbilisi (Photo O. J. Krikorian)

Georgia has been a success story with its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic - not just regionally, but also globally. As of 29 June, there have been just 924 confirmed cases of Coronavirus and 15 deaths. But can Georgia build on that success and use the opportunity to resolve some of the problems that have long plagued the country, and especially in the capital Tbilisi?

Traversing the streets of Tbilisi has always been an arduous task. Cars parked on the pavement block the path of pedestrians and reckless driving in Tbilisi, usually ignored by police, make the situation even worse. The situation with public transportation is just as bad with overlapping routes and drivers often flouting traffic regulations.

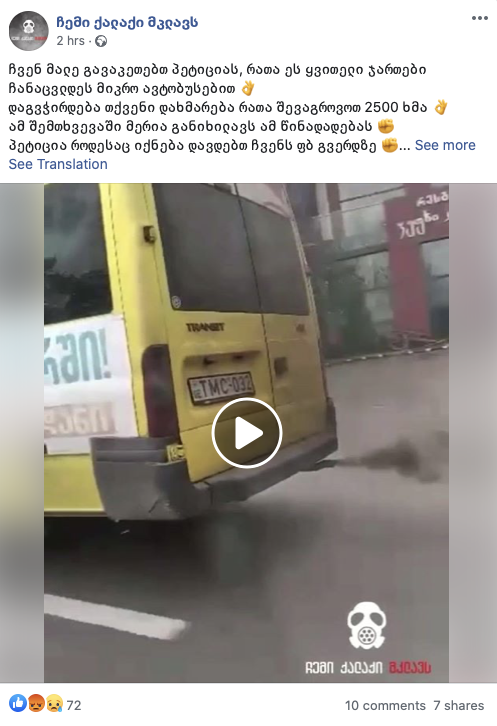

Despite hundreds of new buses purchased in recent years, overcrowding to dangerous levels has been the norm. Mashrutkas – yellow minivans – were similarly bad and significantly increased air pollution. Factor in the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for social distancing, and encouraging alternative forms of transport, and there was a potential disaster waiting to happen.

But, somewhat unexpectedly, as soon as the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic, the government moved quickly. On 18 March, the mashrutkas were suspended and on 31 March the metro and public buses, which also experience severe overcrowding, were halted too. A state of emergency was declared on 21 March.

Most motorised traffic was banned in late April, though likely to prevent people from gathering in large groups for Easter. More seriously, perhaps, the under-resourced public healthcare service could have been easily overwhelmed during the pandemic if traffic accidents had occurred at the same level that has afflicted Georgia for years.

As elsewhere, the lockdown has had other unintended effects. On 20 May the National Environment Agency of Georgia announced that levels of pollution had dropped dramatically to acceptable levels. Previously, the World Health Organization (WHO) had ranked Georgia as 70th among 194 countries for mortality due to air pollution.

More Georgians also took to bicycles in Tbilisi and recently introduced e-scooters, of which there are now reportedly 2,000 in use in Tbilisi and the Black Sea coastal resort of Batumi. Environmentalists and road safety advocates hoped that the experience would encourage City Hall and the government to take further steps.

And indeed, on 22 April, Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze suggested that he might consider prohibiting driving for two days a week even without the lockdown, to build on the environmental benefits experienced.

“COVID-19 completely changed life here and it’s a real opportunity to make some revolutionary changes,” says Gela Kvashilava from the Partnership for Road Safety. “If there is no clean air then there is more of a problem with the pandemic and also generally with health.”

Like others, and contrary to the perception of Georgia as car-owning society, he says data suggests the potential is there. Just 38 percent of households own a car, according to the annual survey conducted by the Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) in Georgia. Other surveys indicate that 20 percent of car owners in Tbilisi use them to travel distances of only 1.5 kilometers.

There has never been a better time to invest in alternative forms of transportation, believes Kvashilava.

“The main thing is to have the political will from the government,” he says. “We already have support from the community because people are fed up with this noise, pollution, and traffic congestion. We’re now at a place where we can see a solution. We need to promote shared mobility, starting from walking through cycling, to public transport.”

Other Georgians also believe that this is possible. Mariam Kvaratskhelia, an Analyst of Sustainable Transport & Climate Change at SUSTAINABILITY.GE, says that the signs of some change are already there.

“In 2017, the first modern cycling paths were constructed on Pekini Avenue and another one is being constructed on Chavchavadze Avenue. I believe the efforts from City Hall show a willingness towards finding greener solutions to the traffic problem. It’s not enough, and few use them for the purpose of mobility, but that is related to infrastructure and socio-cultural issues.”

Kvaratskhelia notes that there has been no attempt to connect the cycling paths, for example. “The cycling infrastructure needs to be developed in other parts of the city and then integrated into one network,” she explains. "There also need to be educational and public awareness campaigns to create a positive image. Cycling is currently associated with poverty or low social status.”

Nevertheless, she is still optimistic and says that Niko Nikoladze, an important Georgian literary figure, brought the first bicycle made by Pierre Michaux from Paris to Georgia in 1889. Such examples could be used to highlight the historical relationship that Georgia has had with transportation other than the motor vehicle.

“By constructing cycle paths on the sidewalk, the idea that a bicycle isn’t a primary means of transportation is reinforced,” she says. “They are separate from the road and the impression that there is no relationship with other road users is reinforced. Pedestrians are an obstacle and this creates problems in terms of safety.”

“Covid-19 showed us an alternative,” believes Kvaratskhelia.

“During the state of emergency, we experienced something that Tbilisi hasn’t before – car-free streets, clean air, and wide, open spaces. I think this revealed the disastrous effects that the traffic pollution has had on the city. People really started to re-think the importance of sustainable transportation.”

Others, however, are more skeptical.

“The optimism is fading away,” says Giorgi Jafaridze who runs a Facebook page, “My City is Killing Me,” that regular posts photos and videos of environmental pollution and other related issues, especially though not only related to transportation. “There have been no actions taken.”

One such example is the case of the mashrutkas, now operating again, rather than be phased out and withdrawn from service. City Hall recently announced that more would be purchased by the private company that operates them. Somewhat unexpectedly, City Hall will foot the bill.

“This is unacceptable,” says Jafaridze, who also plans to launch an environmental website. “The state should not be giving money to a private company whose vehicles have been polluting the city for a long time now.”

But Gela Kvashilava says that the idea is to eventually merge the mashrutkas into the existing public transport system. Nevertheless, Jafaridze remains skeptical. “City Hall announced a development plan for public transport and that might help citizens choose it over cars,” he says. “But we don’t see that today. None of the promises made have been kept.”

He agrees with Kvashilava and Kvaratskhelia on one thing, however. With or without the coronavirus, the situation must change.

To Top

To Top