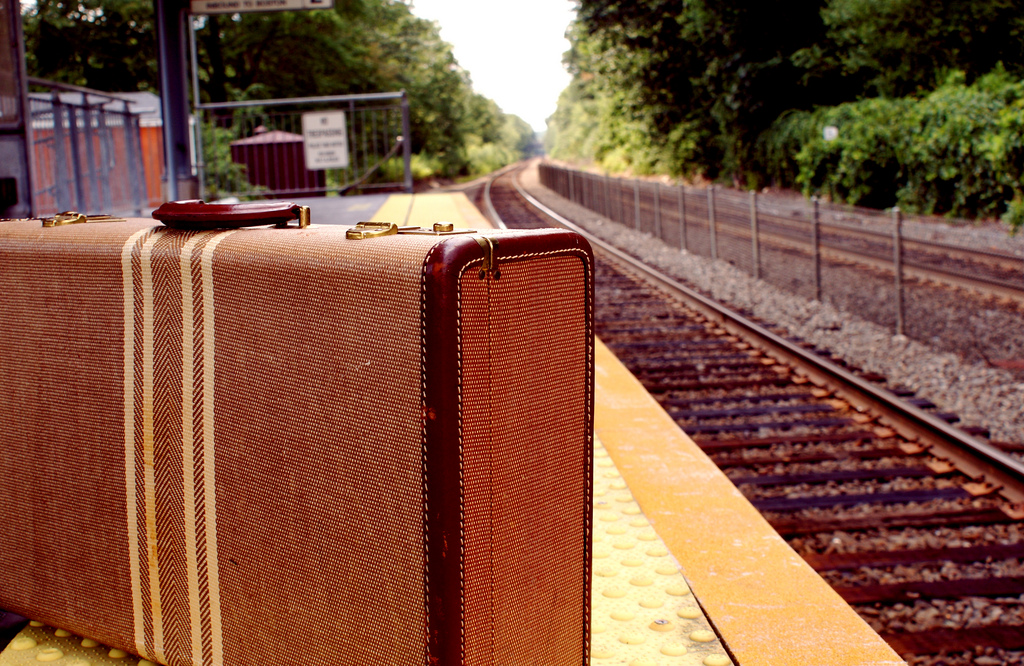

bluebirdsandteapots - flickr

Because of the crisis, about 200,000 Albanian migrants have decided to leave Greece and return to their homeland. A difficult choice for the youngest ones, who have to adapt to a country they do not know

In Tirana everyone calls him “Greg”, the Greek. When he lived in Lagonisi, on Attica's Southern coasts, however, his christening name was “Christos”. Out of the blue, one afternoon before basketball practice, his parents told him that they would have to go back to Albania.

Return or uprooting?

It all happened a year ago, when Christos – Greg had just turned sixteen: his father, a mason, had not found work in six months, and his mother was earning money off the book by cleaning the small villas on the coast. The family could no longer get by. However, for a teenager born and raised in Lagonisi, where he had always attended Greek schools from kindergarten to high-school, leaving for Tirana was like going to Mars.

He could not even read or write in Albanian: what class would he be attending? Grade school, to learn another language from scratch? Not to talk about his friends: “I was lucky enough never to be the object of racism among my peers in Greece. My friends are there. And it is there that I want to return when I can. Here, I have to be home by 10 pm at the latest, because streets are dangerous, gangs riot and fight, as in school in Tirana. In Lagonisi, we could stay out until dawn on the week-ends: we didn't have to spend money, we just joked on the beach or played basket”.

Greg-Christos' is only one of the many testimonies of Albanian boys and girls that the daily Ta Nea has gathered by in the past few days. All teenagers who have had to return to Tirana or Durrës because of the crisis in Greece.

Two hundred thousand returning migrants

According to a survey carried out by Usadis, paid for by the United States Department of State and the Albanian Ministry for Foreign Affairs, about 200,000 people in the past five years have left Greece to return to Albania. So many Greg-Christosses born in Athens or on the Aegean Isles speak very little Albanian at home and learn and play in Greek at school. The word “return”, to them, makes very little sense compared to “uprooting”.

According to the Greek register office, between 2004 and 2012 only, 104.225 children were born from Albanian immigrant parents. In 2004, Greg-Christos was already born. His parents had, indeed, left Albania in 1994, with the dream of setting up their family in the European Union. Their son was born on the seaside: “Now, to go to the sea, I have to ride a bus from Tirana for two hours”, an embittered Christos says.

Torn identities

Little Eleni, 9 years-old, was actually born in 2004: for her, it was easier, two years ago, to adjust to a third grade in Tirana. Though for her older sister Anna, the most awful memory of her young thirteen-year life was when her father had been unemployed for two years and she and her family had to leave Kypseli, a green suburb just outside of Athens.

“In Greece, I did very well in school: one year, I was entrusted with carrying the Greek flag at the national day parade. An honor only given to the student with the highest grades! Now, though, I am afraid I will slowly forget Greek, even though my parents went out of their way to find a school here in Albania where they also teach the language of Athens [editor's note: originally an all-girl school of the Arsakeio NGO, founded in 1836 by wealthy Greek families, for girls destined to become teachers and preserve the Greek language, with five premises in Greece and one opened up in Tirana in 1999].

“My father is having trouble finding a job here, too. We might have to move to another city. But it will be difficult to find a school with Greek as a second language...”

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page: Tell Europe to Europe.

To Top

To Top