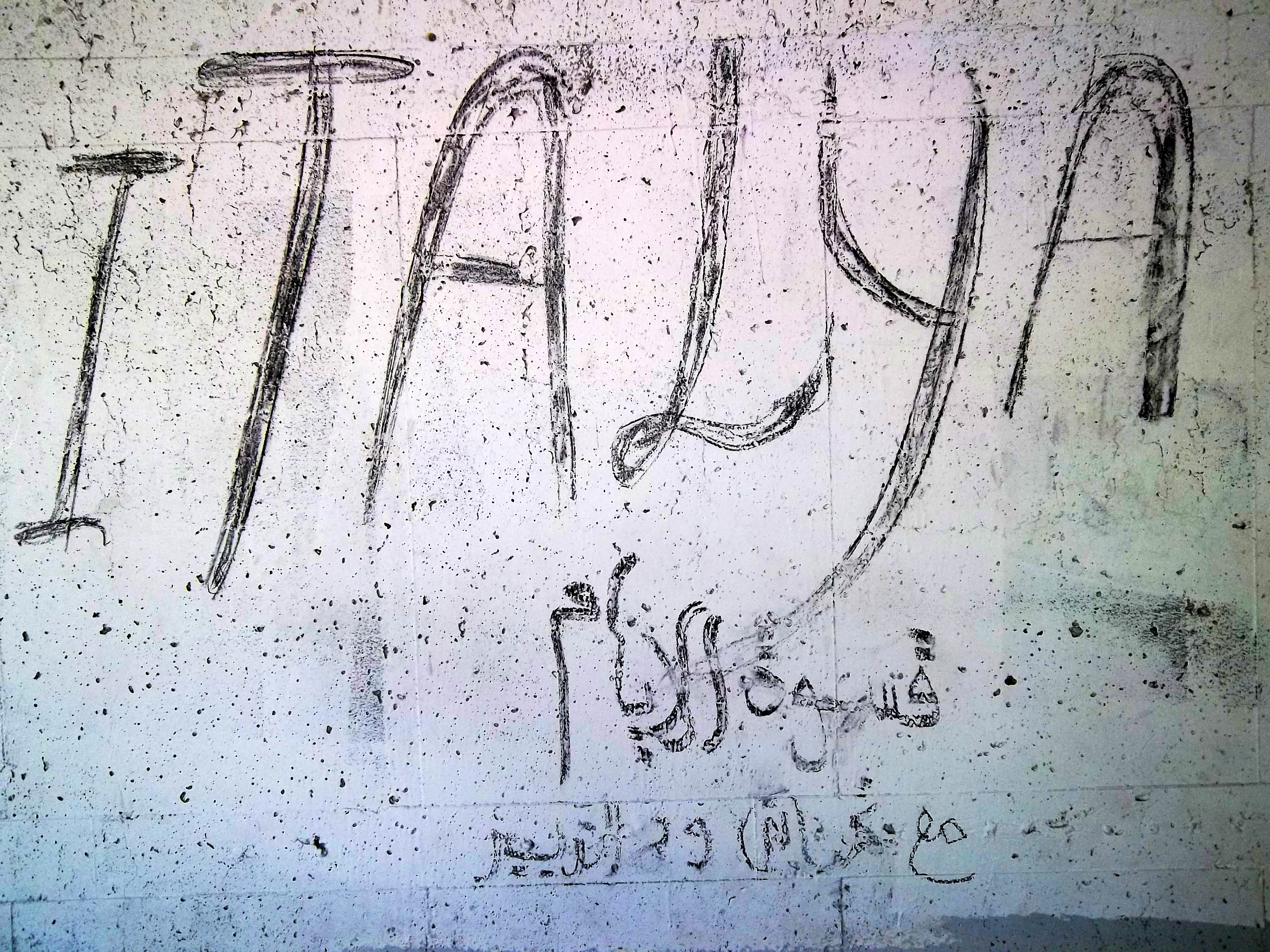

On the walls of Igoumenitsa - P.Martino

In Igoumenitsa the muhajirins dream of Europe. It does not matter if they are there already: for them, the one that counts is on the other side of the Adriatic. Here Mussa Khan too, as many before him, tries his hand with fate.

“They forced us to put all our things in our backpacks, already packed full. Phones, wallets, bracelets, rings, belts, shoe laces, eyeglasses. The policemen were screaming like madmen, but we were the only ones in the group who could understand their orders in English. If you did not answer right away, you would get hit, no matter if you were young or old”. Sitting in the shade of an oak tree in the suburbs of Igoumenitsa, Mussa Khan and Jamal tell of the horrible days spent in the Greek detention center.

After facing the whirlpools of the Evros together, two weeks ago the unlikely couple, an Iraqi Kurd and an Afghan born in Iran, gave themselves up to the Greek police along with another thirty people. They have not parted since. “They used permanent markers. They wrote a number on our hands. They told us it was so we could find our bag when they would release us”. The black mark is still visible on their skin. “In Kurdistan we mark sheep”. Jamal spits on the floor. “In Europe they mark people”.

Saturday morning. Under a radiant sun, the Sofoklis Venizelos docks at the Igoumenitsa wharf. I linger on the deck, I stare long at the green inlet leading to the bay. A natural stage of mountains steeply plunges down in the sea, creating a short line of plane land where the city and the port rise. On a wharf, lined in herringbone style, dozens of trucks are waiting to board.

I resist the temptation to rush off the ferry: Mussa Khan is waiting for me, somewhere out of the port. Groups of Spanish, French and Italian tourists, getting off a ferry that has docked at the nearby wharf, walk past me. The scooters of the port police make spectacular maneuvers among the trucks.

Two off-road vehicles cross the square quickly, disappearing behind the tarps of the trailers. Their flashlights are on, but the sirens are mute. I follow them. The steel of the handcuffs has the same shine to it as the rippling sea water in the background. The dream of three migrants is broken right in front of my eyes, in front of the endless blue of the Adriatic. The pick-up truck shots off with a squeal of the tires, with its human load. The flow of tourists continues uninterrupted. I join them, in silence.

“Salam u alaikeum, kardash! ”. It is Mussa. He appears suddenly, near the exit, together with another boy, behind some parked cars. I do not even have the time to react. “Let’s get out of here. Too many checks”. No formalities for the muhajirins: it is a luxury they cannot afford. We run a short while on the street along the port. Here, too, just like in Patras, video-cameras and electric sensors dot the rugged profile of the fences. A police car drives along at walking pace while we turn into an alley, slipping away.

A long embrace. We light up a cigarette, beneath the shade of an oak tree. Words are hard to get out. Too many faces, too many red herrings, too many ghosts have piled up in the past few weeks, separating us and at the same time pulling us together. “You know”, I tell him, “before this journey, I was against smoking”. He smiles. Jeans, a shirt, sneakers, a nice tidy haircut, orderly backpack. His look does not betray the thousands of kilometers covered. “I am sorry I could not call you earlier”, he tells me, serious all of a sudden. “After the Evros, everything happened so fast”.

He takes a cell phone out of his bag. The monitor is beaded with drops of water. “To get to the ship, we had to walk in water up to our chests. I kept my backpack over my head, but I forgot my phone in my pocket. Fortunately Asif has your number and he sent it to me a few days ago by e-mail”. Asif is Mussa Khan’s cousin, and has been a refugee in Italy for many years. It is thanks to him that a night six months ago I met Mussa, while chatting on Skype. At the time, Mussa was in Mashad, but he was already pondering fleeing from Iran. We have kept in touch ever since.

Jamal sits beside us. He says he detests Igoumenitsa. “How long have you been here?”. Jamal answers without looking at me. “I do not count the days. When I am in Europe, far from it all, I will not want to know how much time I will have thrown away in the jungle”. In the world of migrants, Igoumenitsa is known as The Jungle: scattered in the thick woods surrounding the city, thousands of people survive like souls in the purgatory, waiting for the right ship to carry them to another world. Some estimates talk about 5.000 migrants, but no policeman, no volunteer, doctor, activist or reporter has ever climbed up there to count them.

“I m safe with Jamal”, Mussa says smiling. “As long as I am with him, I will not have to spend money to stay in Igoumenitsa”. I look at Jamal, who does not quit rubbing the small metal wheel of the lighter, releasing sparks in the still air. “I am Kurd, and Igoumenitsa is controlled by Kurd traffickers. I have good contacts here, but they are not friends. I prefer to see them as less as possible”.

To sleep in the Jungle, migrants have to “belong” to a trafficker, who grants them protection in exchange of money. Punishment is inevitable for those who refuse to pay: threats and warnings precede beatings, robberies, stabbings. “We sleep away from the others, though, and every night in a different place. My contacts have offered us a place in the woods”, Jamal says, “but I do not want to owe these people too much”.

Hours go by quick with Mussa, beneath the shade of the oak tree. I listen to the long story of his journey. The sand that the wind and tides have brought here becomes our board: the outlines of Iran, Turkey, Greece and Italy slowly take shape, until the whole itinerary is at our feet. For weeks we have traveled the same roads, we know them by heart. The crucial legs of the journey carry names of cities, neighborhoods, rivers, mountains. Van, Izmir, Istanbul, Edirne, Evros, Thrace, Omonia, Athens. Places that recall in us images and memories in an orderly sequence.

Mussa is my age. He listens to U2. He watches Al Jazeera International and BBC. He chats with friends on MSN, he updates his Facebook profile. He eats kebab and French fries. He stays up late at night, he smokes after drinking coffee. The gap between our life prospects, seemingly ludicrous, is made unbridgeable by one sole irreversible element: our passport. The watermarked booklet that I keep in my pocket allows me to come and go. He has never had one. “What about now?”, I ask him naively. “We’ll see”, Mussa answers hopeful. “We’ll see”. I sense he has something in mind. The sun at its Zenith exasperates the singing of the balm-crickets. We fall asleep resting our heads on the backpacks, numbed by so much chirping.

At 5.30 Jamal proposes his plan for the evening: a swim. To get to the beach we cross the port area. Trucks are stopped by the side of the road. A young Kurd boy, he must be 13, has aimed at an Italian road train. He is about to get himself under the axle shafts when Jamal calls him by his name and tells him a couple of sharp sentences. “What did you tell him?”. Jamal smiles: “To forget about the truck and come dive with us”. The boy stares at the truck, indecision all over his face. Suddenly, crazed, he spits at the trailer, bawling incomprehensibly, and runs towards us. He throws himself on Jamal’s shoulders, as if he were his older brother. He is incontrollable and already foretasting the swim.

Mussa and I are left alone, lying on the sand, while tens of migrants dive from the abandoned wharves of an old building site. The shape of the ferries in transit is net and clear on the horizon, while the sun plunges in the sea. “I have thought about it long and hard. I have to ask you a favor”. The look is enough to answer. “You must buy a ticket for me. Tomorrow I want to try and board with the tourists”.

The night goes by quickly in a house under construction. Rolls of sheathing and sacks of cement are the most comfortable mattress in the world. At 7 I am awakened by pangs of hunger. I have not eaten since yesterday morning. I do not know how Mussa and Jamal can handle it, they have not eaten in weeks. “We are used to it. We will eat in Italy, when we have a lot of food”. I get away with an excuse. Five Euros are enough to buy bread, tomatoes, cucumbers and feta for all. After an initial resistance, Mussa and Jamal throw themselves on the meal. I observe them while they eat and I think of the thousands of people around here who suffer from hunger, accepting it without complaining: indeed, they pay a daily rent to continue living in this hell. This, too, is Europe.

“When I am in the hall of the port in line for passport control, I will have to be careful with the traffickers. The kaçakçılars are better than the agents at detecting us and they are happy to collaborate with the police”. The day goes by with Mussa explaining the dangers he will run during his attempt. “But if I can go into the crowd, I can pass”. Once on the dock, he will try and stay in line with the tourists, hoping that checks are superficial on board too. “The only thing I ask of you is to remain by my side. Together we will stick out less”.

The evening comes rapidly. Jamal and Mussa Khan say goodbye hastily. Migrants do not have energy to waste on being sentimental. Buying the tickets is a mere and quick formality. The cashier asks me where my friend is. “Outside, parking the car”. “Alright, have a good trip”. The Olympic Champion bound to Ancona sails at 11.30 pm. We decide to split until the boarding hour, so to avoid plainclothes agents and traffickers associating our faces.

The hall of the port is packed with people. We get in line. When our turn approaches, we notice how scrupulous the agents are. They check everyone’s id picture and look at everyone’s face with attention. It seems the Schengen agreements have never come into force here. We get out of the line and try again. One, two, three, four times, until the poisonous look of a guard in a blind spot in the hall alarms Mussa. “We have been detected. I have to go. You get in line, I will see you outside”.

There is a half hour to departure. Tourists are slowly boarding, while cars and trucks are lining up in the day-lit square. “Listen to me and don’t turn around”. Mussa’s voice is clear, even with the noises of the port. He is hiding behind a bush, a few meters beyond the fence. “I will try and jump the fence. Wait for me in front of the ferry’s footbridge”. I see his shadow move away, until he disappears in the darkness.

The half hour has long passed by. All the tourists have boarded, just the trucks continue to noisily roll on the ramp. I do not know what to do to still linger in this spot, the police has noticed my unusual presence. When I have lost all hopes, my phone rings. “I jumped! I am almost there”. Mussa is running towards me. We quickly get on the metal footbridge. We are on the ship.

An alarm goes off. Four agents coming out of nowhere hurl themselves against us. Trained hands grip us under our arms. Shoves, screams, kicks. The hunter has caught his prey. The footbridge again, this time going the other way. The tragedy unfolds: we did not escape the checks onboard the ship.

The pick-up truck of the police is ready at the wharf. It is the same truck on which yesterday morning I had seen the dream of three handcuffed muhajirins being broken. Mussa is thrown in the middle. For the last time, we cross glances then, enraged, I scream: “I am Italian!”. I take the damn passport out. A man from the ship’s security service controls it. He nods, while the policeman closes the door to the truck. Mussa disappears forever. I walk the footbridge for the third time. The Olympic Champion sails with a 10-minute delay. Destination Europe.