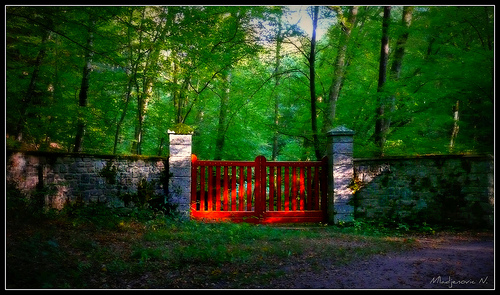

(Voyageur Solitaire-mladjenovic_n / Flickr)

Although it was the first country in the region to sign a Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU, Macedonia seems to have slid backward in the accession queue, and will probably be stuck in a waiting room for a long time

Many people in the Balkans dream of joining the European Union. The dream remains elusive despite sometimes appearing so real that it can almost be touched before fading again.

Croatia seemed almost at the gates of the EU. Some said perhaps by the end of 2010. Now, conventional wisdom indicates that accession might occur in 2013.

Although Macedonia has never had a tangible entry date, at times the government felt their application was on a fast track. In April 2001, Macedonia was the first country to sign a Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU. The Croatian government signed it in October of the same year. Serbian officials, for example, only signed it in 2008.

At that time, the SAA was Macedonia’s reward for its constructive role during the Kosovo crisis. Many hoped that Macedonia would soon join the EU. Then, unfortunately, immediately after having signed the SAA, violent ethnic conflict erupted in Macedonia. Fortunately, the violence was short and confined.

The EU candidate status finally arrived in December 2005 as a compensation for the failed territorial referendum, which could have pushed the country back into ethnic violence. Croatia achieved EU candidacy status in mid 2004. In addition, Macedonia’s candidate status came without the usual date to start negotiations. Croatian government officials started negotiating in 2005. Macedonia needed to wait four more years and finally, in autumn of 2009, the European Commission recommended setting a date to start negotiations with Macedonia.

As many expected, the European Council could not set a date, because of Greek pressure over the name dispute. In December 2009, Brussels gave Macedonia six months until the end of the Spanish Presidency, to resolve the dispute with Greece in order to be able to start accession talks. That time expired before the European Council meeting mid June. Predictably, nothing happened on the name issue. Rumours indicate that Macedonia will not be on the agenda of the June meeting. Accession negotiations probably will need to wait for some better times.

The dispute with Greece is Macedonia’s deepest trauma since independence. The conflict has been blocking the country’s progress in many ways for the past 19 years.

However, this is not the only issue challenging the country’s accession. Since the last Commission’s report, Macedonia appears to have slid backwards. Different sides have warned that reforms have stalled.

The country goes “two steps ahead, one step back” said EU Ambassador to the country, Erwan Fouere, in mid May during a lecture at FON University in Skopje. Fouere said that political parties did not engage in sufficient dialogue, and that stronger efforts were needed in the judiciary, public administration reform, and the fight against corruption.

The EU headquarters recently had (at least) several issues with Skopje. A controversial law on anti-discrimination was passed in direct opposition to recommendations by the EU.

At the end of May, Zoran Thaler, the EU Parliament rapporteur on Macedonia, directly expressed doubts over the Macedonian government’s recent course. In Skopje, Thaler said, “There are feelings in Brussels that EU integration is no longer a priority for the country.”

This could lead the EU to reassess and even take Macedonia off the agenda for EU accession. EU funding for the country could also be suspended; Thaler added, this funding is given to prepare candidate countries for accession. If the country is not interested in accession, the funds might be reduced.

“We remain committed to EU integration,” responded Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski. He said, “If there are feelings that we are not committed, then they are unfounded.”

The growing distance has nevertheless been visible. Last month, the media reported on an alleged instruction by the Deputy Prime Minister for European Integration, Vasko Naumovski, to his staff, that he must approve all direct contact with staff of the EU Delegation. Only top-official-level communication would take place.

This cutback in communication will affect the country’s relationship with the EU because the complex accession coordination process requires discussing hundreds of detailed question that emerge daily . In response, EU Ambassador Fouere said he felt contacts should be closer and more direct at all levels.

The government in Skopje is frustrated by the lack of support it gets from the EU in the dispute with Greece. Prime Minister Gruevski recently called upon EU countries to help resolve the dispute and reconsider their position of unconditional support to Greece. The lack of understanding by EU members fuels resentment in Skopje and, out of spite, the government almost seems to do some things in opposition to Brussels. That may not be the most prudent of policies.

While EU diplomats often say that “life is not fair”, in the sense that they have understanding for Macedonia’s position, they must take the side of the member of the club. The neutrality that EU countries assume with respect to the issue, in essence, sides with the Greek government.

Sulking like a little child whose feelings have been hurt would not help Macedonia, and this is exactly what it seems to be doing currently. Spoiling the relationship with everybody, just because of anger is not the way forward. Effective international relations require maturity.

The government waits for the Commission’s annual assessment released after the summer holidays. If nothing changes in the meantime, the report would probably be negative. The waiting room could be Macedonia’s living space for an indefinite period.

To Top

To Top