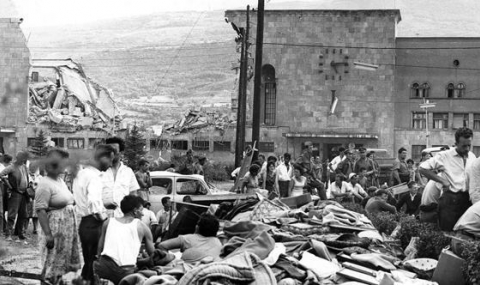

Skopje after the 1963 earthquake

The Macedonian capital remembered the 50th anniversary of the devastating earthquake of July 26, 1963. On that day, the city stopped breathing

One of the first things visitors to Skopje notice is the building of the old train station, standing at the opposite end of the main street stretching down from the Stone Bridge. The building is half demolished. It was left like that for remembrance. Its remaining functional part is now a city museum. The large clock above the main entrance stands still at 5.17 am. It has been pointing to this hour for the past 50 years. Since 1963. It is an hour people from Skopje will never forget. It is when, for a moment, the city stopped breathing.

The Skopje earthquake

This July 26, Skopje remembered the 50th anniversary of the most dramatic event in its recent history: the Skopje earthquake. On that same day in 1963, in a matter of seconds, the seism destroyed 16,000 homes and damaged some 30,000 more. 1,070 people lost their lives, of whom 120 children. Some 3,300 were injured, several hundreds of which were permanently disabled. An estimated 200,000 people lost their homes.

People remember that the earth went on moving for hours after the main earthquake. Hundreds of smaller quakes were registered by the end of the year. Well into the 70s, when the writer was a young boy growing up in the south of the country, a sort of panic was still strong nationwide. At the smallest sign of earth-quaking, which is not infrequent given that the larger Balkan region is seismically active, people would rush out of their homes and spend the night under the open sky. Reluctantly, step by step, listening to the earth, they would enter their homes the next day.

Seismologists say that the Skopje earthquake was not very strong in general terms (9 degrees MCS). Its epicenter, however, was close to the surface, which enhanced the demolition. Old and poorly constructed buildings added to the disaster. According to experts, if the same seism would hit today, nothing like that would happen. After the earthquake, builders started observing obsessively seismic construction rules. Back then, however, the quake was strong enough to completely wipe out the parts of the town closer to its epicenter. The city then had 3 seismographs. All of them were broken by the power of the tremor, and information on the actual strength of the quake came from seismic centers in other cities.

Help from Yugoslavia and abroad

All until the very end of former Yugoslavia, JNA (Yugoslav People's Army) soldiers were well-liked in Skopje. With several large barracks in the city itself, they would flood the city center on weekends in their green uniforms. People would greet them and they would get an occasional smile from a girl while eating the last ice cream (most of them young boys age 19) before running back to the barracks at dusk. One of the reasons for this sympathy lies in the fact that they were the first ones on that July morning to rush out and start clearing the rubble looking for survivors. In the following hours, they were followed by miners from the Macedonia and Kosovo mines, and finally organized humanitarian teams from cities throughout the country started to arrive. Open air emergency medical centers started operating. The heavily injured were sent by planes to other cities. Public kitchens sprung up.

In the next days, help from all over the world joined in the humanitarian effort. Non-aligned Yugoslavia was at the edge of the iron curtain, and both the West and the East were eager to help. According to some accounts, Macedonia was at the time the only place to host both Soviet and American teams, working for the same cause. Countries competed in sending relief aid and reconstruction assistance. In the following months, Skopje was called city of international solidarity.

The dramatic event changed the lives of many in Skopje, and deeply affected the lives of others. Lawrence Eagerburger, then an official in the US Embassy in Belgrade, and later US Secretary of State, was at the forefront of the US humanitarian and reconstruction assistance. On account of his fervent, energetic involvement in the relief effort he was nicknamed Lawrence of Macedonia.

In the following months, the UN General Assembly convened on Skopje and helped to prompt the international reconstruction effort. On 14 October 1963 it unanimously voted a resolution to provide assistance to the Yugoslav government for the Skopje reconstruction. By some estimates, the material damage caused by the earthquake amounted to 15% of the Yugoslav GDP at the time.

End of the Old Skopje

The earthquake was the end of the Old Skopje. The pre-earthquake Skopje can now only be seen in the yellow photos remaining from that era, hung on the walls of the city kafanas (restaurants). Many of the city landmarks were destroyed.

The name which emerged from the rubble was that of Kenzo Tange, a Japanese architect who is credited with the urban plan of the post-earthquake Skopje. Many buildings of the post-earthquake period, stylistically similar, are commonly, and often incorrectly, referred to as the “Kenzo Tange buildings”.

The effort of others has also left a mark. Quite a few dull-looking, grey, 5-story prefabricated buildings sprawled across the city dating from the time are still referred to as the “Russian buildings”, allegedly resulting from the Russian contribution in the reconstruction effort. The Russian buildings are indeed not stylish, but some of them are surrounded by vast areas of green, with large parks with trees where children can play (Karposh 4, for instance). Unlike the planners of Skopje's recent chaotic construction boom, who for the sake of profit would root up the last leaf of grass, and devoid streets of pavements, the planners of post-earthquake Skopje had a different design.

The anniversary

The anniversary was marked with a range of events and ended with a gala concert and a performance called “Skopje Remembers” in the city's central square. At the end, 1,070 lanterns were flown into the sky, one for each of the victims of the earthquake.

On 27 July, the daily Nova Makedonija reprinted 4 pages from its edition of that same day 50 years ago. Back then, the edition was printed in Pristina as the newspaper's building was unsafe to enter.

One of the most beautiful songs wrote about Skopje, Skopje You Will be Joy has been inspired by the earthquake. Written for children, but sang by adults alike, it starts with the lyrics “gradot ubav pak ke nikne”, the beautiful city will rise again.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page: Tell Europe to Europe.