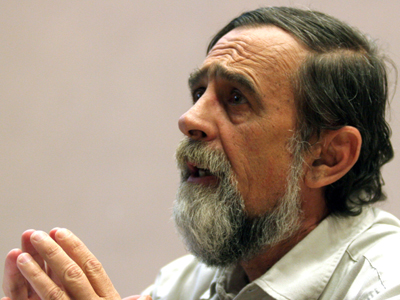

Vintila Mihailescu

Weeks of street demonstrations in Romania, where citizens have rarely protested against the “power”. We have discussed it with Vintila Mihailescu, an anthropologist amongst the most lucid intellectuals in Romania

Street demonstrations in Romania started in mid January and led to Prime Minister Emil Boc’s resignation. They have momentarily come to a halt because of unfavorable weather conditions, under which the country is literally stuck.

Despite demonstrators protesting against the harsh austerity measures imposed by Boc’s administration and demanding his resignation, the nature of the protest was, per sé, wider and more complex: it indeed involved the whole of Romanian society.

What is, thus, the meaning of this protest for Romania and what are the possible consequences?

We have discusses with Professor Vintila Mihailescu, Romanian leading anthropologist. Born in 1950, he was director of the Museum of the Peasant in Bucharest and he is presently director of the anthropology master’s at the University for Political Sciences in Bucharest. Since 1998 he has been writing regularly for the critical independent cultural magazine Dilema Veche.

The Romanian people is not so used to street protesting…

The January uprising took everyone by surprise, including the demonstrators themselves, I believe. It had been many years since we had last taken to the streets. Trade unions practically do not exist, so the ability to mobilize for a protest, strike, demonstration had been lost.

What was special about this time is that the protest was absolutely spontaneous and mobilized so many people in just a few minutes: people’s long-time discontent was brusquely triggered.

The spark was lit by a gesture by President Băsescu: he irritated the whole Country forcing a government official to resign live on TV. The official is admired by everyone for having established, in Romania, the emergency room system. The system works very well and is a model for the whole of Europe. It represents citizens’ right to life, the guarantee that if something happens, there is a service that works. It was one of the Romania's few services that worked and with which all people were happy. When the President made this gesture – arbitrary, excessive and tyrannical, by the way – people literally felt their lives were being threatened.

Once in the streets, immediately after Băsescu’s declarations, the protest was not only against the health system but against all problems of the Country.

Comparisons have often been made between today’s demonstrations and the ones from 1989 and between Ceauşescu and Băsescu. What do you think about this?

It is a metaphorical and superficial comparison, made mainly because demonstrations started in University Square, as they did in 1989. But they are not the same thing. First of all, the present demonstrations have mobilized a lot of people but not the whole Country. In 1989, instead, the whole of Romania had mobilized and people knew very well what they wanted, they had a plan, they wanted to overthrow the regime, they had very clear demands.

Right now, though, we are facing demonstrations of a “psychological” nature more than a political one, whereby people express discontent, but you cannot really say there is a clear political program to it. In the streets, you heard ‘We want early elections, we want the right not the left, we want another Constitution…’ but there are no clear political demands.

Does this also go for the comparison between Ceauşescu and Băsescu?

Of course. Băsescu has had ‘dictatorial excesses’ too, he has made arbitrary choices on his own, but to say that we are now living in a society like in Ceauşescu’s times is an aberration. We still live in a democratic society: we can freely talk on the phone, for instance. That would have never been possible with Ceauşescu: one second later the Securitate would have been knocking on your door.

Have Intellectuals played an important role in the demonstration? What is it?

It has to be clear that this is a “work in progress” uprising. There was not a clear list against which to protest, at the beginning. It has been created en route. The protest from day 1 is not the same as that from day 3 and week 3. Only now, or at least until weather conditions and snow worsened, have groups started forming, and making clear political demands.

Do these groups belong to a political affiliation or party?

There is another interesting element to underline. We can say there are practically two uprisings. On one hand, there are people in their mature age, some of them are retired or close to retirement, who have demands concerning pension plans, austerity laws and poverty conditions. Their protest is thus focused on the present.

On the other hand, there are young people’s groups, who are more active and organized, who look at the bigger picture, more in perspective. The first demand from the first group was a change in government, while for the young, this was important but not fundamental.

Indeed, when you put things in perspective, it makes no sense to change a government with another one that will do exactly the same job. What they wish for is more of a fundamental change in the political establishment and not only the government. A change in the style of doing politics and not just in the present strategy. These are more general demands that call for a longer fight.

Are these young people organizing in political groups with a pragmatic program?

No. In no way did the young, but also all the people who were in the streets, allow politicians to enter. Some members of the opposition did try; the unions and some public characters tried to take to the streets and say ‘I’m with you, let’s do this together’. However, they were kept away from the streets. People have made it clear that they no longer trust politicians.

In an article off Dilema veche you spoke about a ‘creative uprising’. What did you mean by that?

What seems to me to be most peculiar and significant to this uprising, and at the same time the most important, is that the young desire, they feel the need for political communication; that is why they are demanding that the language of this communication change. We are at a dramatic breaking point between people and the political class, we have started speaking different tongues, we no longer understand each other under any point of view.

The serious mistake is that the messages from the leaders have recently been more and more messages of contempt, an absolutely incredible contempt: ‘Romanians are stupid, the population is stupid, society does not deserve us, you are worms, you are plebs…’ and I am quoting politicians, I am not making this up!

The moment someone representing you says that the people he leads are stupid and lazy worms…. You cannot expect to establish a social and political dialog. The lack of communication between the political class and society is an old story but it has rapidly accentuated in the past few months. That is why I speak about a creative uprising, to show the way the young, the people in the streets, are on the way to change this language, to explain to us: ‘We no longer want to speak your language’.

There is extraordinary creativity in the slogans of the demonstrators, they are often ironic, they change from one hour to the next… I could say it is a sort of comedy unraveling in the streets, in which new messages and new slogans are invented. There are millions of slogans and each time people take to the streets, there are new ones.

In this case, the peak of creativity was reached reinventing a new language with which you can communicate. Why have I spoken of a creative uprising? Because it looks a lot like what today is referred to as creative city or urban art and many of these young people demonstrating have worked with NGOs for urban revitalization. It is a sort of urban revitalization strategy but that is now on a political and national level and not only on a neighborhood level.

The media have made a comparison between the Romanian protest and the Arab Spring. Is this comparison opportune?

They have nothing in common. These demonstrations have had an almost playful nature to them, determined but not violent, they have nothing to do with the Arab Spring massacres. There, people fought with weapons, people died, it was practically a civil war.

In general, how have Romanian mass media covered this? How have they read and told about this protest?

There are two groups of mass media, in Romania. One group comprises public TVs but, despite that, it is completely subordinate to the political power. These TVs reported that it was only two or three hooligans and showed videos of these youngsters throwing stones and Molotov bombs. They did not show that the people were in the streets, that they were unhappy.

A second group, however, reported the discontent and how the whole population was in the streets. If you took the two versions, it looked like two completely different situations.

Do you think an expansion of the protest from Romania to neighboring Countries is possible?

It is very hard to say. I have personally had signals from friends in Bulgaria and Serbia who asked what was happening, with admiration. But that does not mean that things can expand that quickly.

Indeed, the main question is not so much whether the protest will expand outside Romanian borders, but more if and how it will continue in Romania.

Street demonstrations have now been suspended because of weather conditions. What is interesting is to see whether they will start again and how. In my opinion, they will continue as a sort of ‘surveillance’, a ‘watchdog’: at the first mistake by the politicians, people could take to the streets again, but everything is in stand-by right now. According to what I believe, the uprising will continue, not necessarily as an ‘uprising in the streets’ but more as an ‘uprising from the streets’, an uprising of society that will not always be linked to street demonstrations. We could talk about a “chronic” uprising more than an “acute” one.

Do you see in this protest the seed of a new social and political movement where new generations could have a more active role?

Categorically yes. Even more than that, and I think this is the most important thing, the fact that we can talk about a return of the young people to the political scene, not necessarily politics, but at least the political scene.

As it happened in other states as well, the young have depoliticized, they are no longer interested in politics, the percentage of non-voters amongst them is very high.

This uprising shows that the young are starting to develop a political awareness and returning to the political scene. I teach in University and I meet many students: I think we cannot talk about an actual political awareness on the part of the young. From this point of view, this uprising has been important not so much for the number of people who took to the streets but for the changes it will bring on the medium- and long-terms.

Among the various slogans, is there one that you believe to have better represented this protest?

No, absolutely not. The slogans are very different and are all very representative. I would actually say it is the contrary. What is representative is not one slogan but the diversity of the slogans.

To Top

To Top