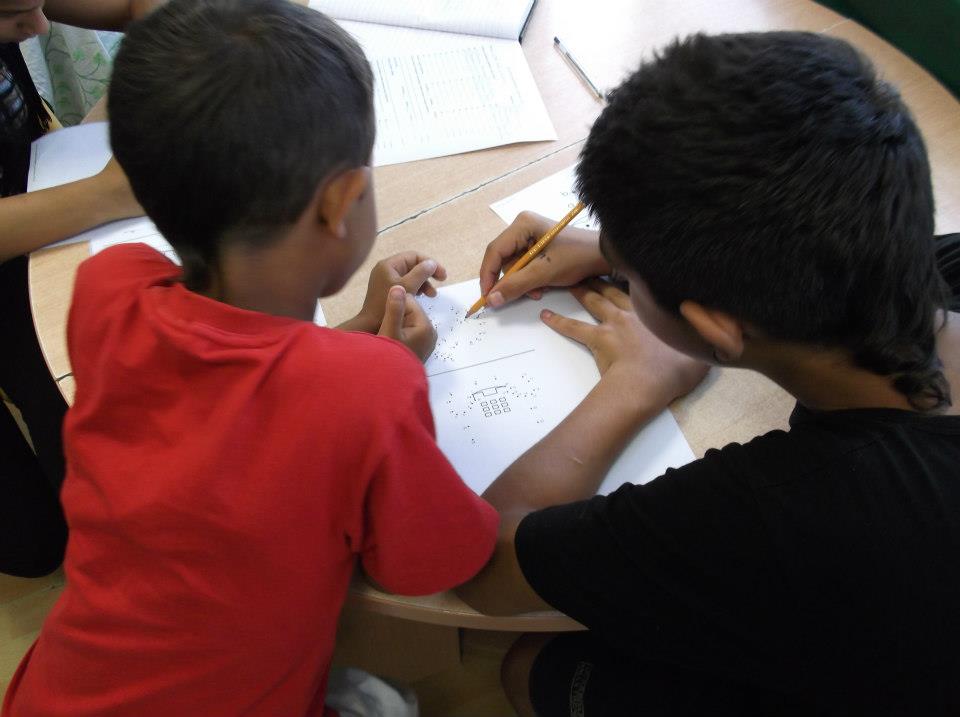

Street children in Belgrade (From the Facebook page of the Svratiste )

There are more and more children living and working on the streets of Belgrade. The institutions are having a hard time dealing with the phenomenon. A temporary daycare center that has become a model for the whole region, the Svratište, recently risked shutting down

Those living in Belgrade bump into street children more and more often, almost daily. When moving around the city, it is not rare to come across children washing windshields at streetlights, helping with the collection of scrap material, singing and playing to entertain passersby or begging. It is easy to see them in the suburbs but also on the crowded streets in Belgrade’s center. Many of them are Roma. Their personal stories, as the specific reasons that have forced them to live (and survive) on the street, are many and diverse. But what weaves their vulnerable existences is the serious risk of being used, abused and neglected.

One of the most tragic aspects of this phenomenon is that very often the first to exploit the street children labor are the parents or relatives. As those dealing with the issue know very well, this raises a moral dilemma: on the one hand, it is legitimate to accuse those adults who exploit their children and fail in their responsibility to ensure them a decent physical, emotional and intellectual growth; on the other, for some families who are extremely poor and in need, the work of these children is one of the few resources available to “get by”.

International laws include child labor within human trafficking, a wider-ranging crime (see the United Nations convention on organized crime stipulated in Palermo in 2000). In a recent conference, the representative for the Center for the protection of victims of trafficking, Sanja Kljajić, pointed out that the most common forms of child exploitation in Serbia are forced labor, begging and prostitution. Mitar Đurašković, the national coordinator for the fight against human trafficking, has confirmed that, in the Country, the number of children working and living on the street (often with their families) is constantly growing.

What the city does

There are two institutions in Belgrade which deal with street children on a full-time basis. One of them is Prihvatilište, a public facility managed by the municipality that welcomes various categories of minors in trouble, including street children and those with no parental care. The other one is Svratište, a temporary daycare center founded over 6 years ago and managed by a local non-governmental organization, the Centre for the Integration of Youths (CIM).

The Prihvatilište was designed to welcome people between the ages of 7 and 18 in particularly critical conditions and for a period of 30 days maximum. The center has been there for over 50 years but has been operating in a critical state. Not only is maintenance poor, but the space – which includes 16 beds – is far from being enough to host all the minors in trouble who are entitled to care.

The Svratište is a safe place where street children can “rest” (meaning of the center's name), day or night. A team of professional educators is there to welcome them: pedagogues, social workers, volunteers, a psychologist and a nurse. At the Svratište, children can rest, wash, eat, play, receive medical and psychological care, but also learn together what their rights are and how to assert them before the authorities.

On average, the center hosts 30 children a day, but the number rises to 70 during winter. The active regulars are 140, but the total number of children that benefits from the care of the center all year long exceeds 600. They are mainly boys and the average age ranges between 10 and 14. The majority of them is Roma, and their families live in informal settlements in Belgrade's suburbs. Along with the center's staff, a team of social street workers visits the most critical areas of the city - the “hot spots” - to build contact with street children and their families.

Svratište makes a plea to avoid shutting down

Despite operating in precarious conditions, the two institutions have never failed to provide their services in the course of the years. However, on March 22nd the CIM staff, the organization that manages the Svratište, announced the upcoming closing of the center. An announcement released to the media explains that the reason for the decision is linked to the center's funding mechanism. The Svratište is indeed funded, so to speak, on a “project” basis. This leads to an uncertain and precarious condition that the CIM defines as 'unbearable'. Hence, the tragic announcement: either the funding system is changed by the end of March or the Svratište will be forced to close on April 1st.

The total budget of the center is about 230.000 Euros per year. Out of this amount, 130.000 Euros are paid by the Belgrade municipality's Secretariat for Social Protection. The remaining 100.000 Euros, instead, come from private funding (civil society organizations, companies and individual benefactors). Whatever the origin of the funding, its allocation is on a project basis, thus with minimum guarantees of continuity. As per what the CIM states, this system does not allow the center to operate efficiently. Indeed, the social re-integration of street children is a long-term process that usually lasts a few years. The situation is worsened by the contract with the municipality terminating at the end of 2012. Whether it is going to be renewed is still unknown. As if this were not enough, the municipality is a few months late on payments. It so goes that the center's employees have not received their salary since January.

The CIM requests that the temporary daycare center for street children be recognized as “social service” to all effects (as provided for by the law on social protection in force in 2011) and that the Svratište no longer be financed on a project basis but through a public bid. This would guarantee substantial and continuative support to a service whose importance has been publicly recognized by the city of Belgrade.

The announcement of the center closing down was thus a sort of “ultimatum” to the competent Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Policy: if the Ministry would not act by the decisive date of March 29th, then the center would have shut down.

The countdown

On Friday, March 29th, the atmosphere at the Svratište was restless. Some children in front of the TV, some others drawing, surrounded by boxes, ready for the imminent (but not yet final) moving. Managing the center during those decisive hours were Dragana Teodorović, social worker, and Jelena Vulić, psychologist. Dragana was very worried while confirming to me that, if no answer arrived by the end of the day, the Svratište would be forced to shut down. The boxes would have been brought to the day center in Novi Beograd, a center that provides similar services but could never fully cover for the Svratište because of the distance and the limited working hours.

Jelena proudly told me that the Svratište, founded a few years ago by some enthusiastic students and volunteers who started taking care of street children in Belgrade, has in time become a model experience for both Serbia and the region: “The daycare centers of Novi Sad and Niš were opened in the wake of our center, along with five centers in Bosnia Herzegovina, with which we communicate and exchange experience regularly”. Dragana added that the Svratište has developed a network of virtuous relations with other institutions in the city, such as the centers for social work and also the Prihvatilište.

While we were talking, the children continued their activities, only apparently unaware of the uncertain destiny of the center which, for many of them, has become a second home. “This is a dramatic and stressful moment”, Jelena said, “and tension has arisen among us and among the children as well. Reactions to the news that we are possibly shutting down have been diverse. Some children, especially those who have been here the longest, are totally incredulous: for them, the Svratište has 'always' been here and will always be here. Other children express rage and anger towards 'those who want us to shut down'. Others are afraid, lost and keep asking 'Where am I going to be Monday?'”

Epilog

In the end, the answer from the Ministry never arrived. On Monday, the doors to the Svratište remained closed. Reactions, though, were quick in coming: as early as Monday morning, about a hundred people, friends and supporters of the Svratište protested in front of the Secretariat for Social Protection of the municipality of Belgrade (video ).

It is amidst this uncertainty and worries that the CIM staff and the Secretariat sat down together, on that same day, for an “emergency meeting”. The outcome was positive: the CIM agreed to reopen the doors to the Svratište right the next day, Tuesday, and the Secretariat formally committed to meeting with the CIM on a weekly basis during the month of April, with the objective of solving the problem of sustainability of the center's activities. This is evidently not an actual happy ending, as a definitive solution to the original problem has not yet been found.

It is painful to see how a model institution such as the Svratište is forced to recourse to an ultimatum – and in a way a bluff – to call the attention of the public authorities to its difficulties. Threatening to shut down was probably the only way the Svratište could hope to be successful. What is certain, though, is that once again the ultimate victims of this painful event are those who live in the center, the tens of children and teenagers who spent days in fear of being deprived of a service that is vital to their well-being and often their own survival.

This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page: Tell Europe to Europe.