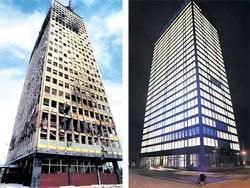

Belgrade, Generalštab (photo F. Sicurella)

15 years after the NATO raids, Serbian society is dealing with a recent past marked by diverging narratives

If the buildings of Belgrade could talk, the story of Serbia's troubled transition to democracy would take the form of a tale in three voices.

The voice of the Ušće skyscraper, which stands between the barracks in Novi Beograd and used to be the seat of the Yugoslav League of Communists.

The voice of the state television building (RTS), nestled behind the church of St. Mark, just a few steps from Tašmajdan park.

The voice of the Generalštab, the majestic modernist-style building that used to host the headquarters of the Ministry of Defence and of the army (formerly of Yugoslavia, then of Serbia), with the two wings overlooking one of the crucial crossroads of the city centre.

The three buildings would start by talking about the prestigious function that each played in the Yugoslav past.

Then came the '90s, so their three stories would converge into a one narrative of how Slobodan Milošević bent them to his own lust for power, turning them into bastions of the regime.

The story would culminate in April 1999, when all three buildings were bombed by NATO aircraft during Operation Allied Force, aimed at forcing the Milošević regime to negotiate the cessation of the Serbian offensive in Kosovo, thus limiting the humanitarian catastrophe that had sprung.

From that point on, however, the narrative would split again in three different stories related to the different routes of memorialisation of the three buildings.

The Ušće skyscraper, turned into a mall in 2005, would speak of itself as of a symbol of the abolition of the socialist past and the entry of Serbia into the liberal-capitalist system.

The RTS palace, where 16 employees and journalists were killed in the bombing, would present its gutted face as a place of official mourning and protest.

The Generalštab, finally, would offer the emptiness of its two craters as symbol of the loss of memory and failed commemoration. The palace, indeed, does not carry any commemorative plaque.

A controversial anniversary

It has been exactly 15 years since the NATO bombing. In 1999, for nearly three months, NATO aircraft dropped bombs on Serbia's key military positions, but also strategic targets such as bridges, factories, and public buildings. The operation achieved the expected result and forced Milošević to withdraw the army from Kosovo, but cost the lives of 500 civilians. The legitimacy of the military intervention, not ratified by the United Nations, and its political record overall remain the subject of bitter controversy.

A few days ago, the day of remembrance was celebrated for the civilian and military victims of the bombing.

The Serbian political elite did not miss this important event.

President Nikolić visited Varvarin, a town in central Serbia where 10 civilians died as a result of the bombing of a bridge.

Former prime minister Dačić, recently replaced by Aleksandar Vučić, laid a wreath of flowers on the hill of Stražević, one of the hardest hit military targets.

Several ministers, representatives of local governments, and army authorities took part in commemoration ceremonies in various locations around the country.

The RTS case

The most dramatic and touching ceremony was held at the RTS palace, one of the three voices of our story.

At 2:06 am, the time at which the missile crashed through the building on April 23rd, 1999, the directors of television and the relatives of the victims gathered around the memorial plaque and lit candles in memory of the fallen.

The plaque bears the inscription "Zašto?" (why?), a sharp question that has received conflicting and equivocal responses for years.

The Association of Journalists of Serbia (UNS) repeated it once again, loudly demanding the completion of the investigation into the responsibility of what many do not hesitate to define a 'war crime'.

The Commission of Inquiry investigating the murders of journalists , perhaps the deepest wound in recent Serbian history, promised to strive to shed light on the matter.

Former RTS director Dragoljub Milanović has already served 10 years in prison for not ordering the evacuation of the building in time.

Now the focus is on the alleged responsibility of the heads of the army and the Ministry of Defence, suspected of having concealed the news of the impending attack and thus set Milanović up, as he has always claimed.

The uncertain fate of Generalštab: a semiotic look

"The builder broke off a piece from the mountains where the decisive struggle for the fate of the peoples of Yugoslavia had been consumed and brought it to the centre of the capital".

With these words Nikola Dobrović, Yugoslav partisan and distinguished modernist architect, described the meaning of the Generalštab, his most grandiose achievement.

He was probably referring to the famous Battle of Sutjeska, or rather to the even more famous monument that 'freezes' the breach of the Yugoslav partisans surrounded by the Axis powers.

In a recent essay on the Generalštab, scholar Vladimir Kulić writes that the 'void' between the two wings of the building meant to symbolize the Yugoslav project, representing its creative energy and openness to the future.

After 1999, this fertile emptiness was replaced by the negative emptiness of the craters made by bombs. Today, writes Kulić, the Generalštab poses a dilemma – which void to commemorate, which void to identify with. The one created by Dobrović or the one created by NATO?

Semiotician Francesco Mazzucchelli, a scholar of architecture in conflict zones at the University of Bologna and the author of Urbicidio, il senso dei luoghi tra distruzioni e ricostruzioni in ex Jugoslavia (Urbicide, the sense of place between destruction and reconstruction in former Yugoslavia, 2010), studied this dilemma in depth.

OBC asked him to reflect on the relationship between the uncertain fate of Generalštab and Serbian society's fatigue in dealing with the traumas of the recent past.

"The bombing transformed the Generalštab in a sort of 'natural monument' in Belgrade", says Mazzucchelli. Its location on Kneza Miloša, surrounded by many embassies, made it the core of a specific symbolic space, the “space of confrontation and conflict between the Serbian people and the international community”. A core that functions as “a metaphorical urban scar which starts bleeding again on special occasions", as happened with the protests against the independence of Kosovo in 2008.

Between semantic ambiguity and cultural memory

The Generalštab, continues the semiotician, is a "load of semantic ambiguity" that stubbornly resists commemoration as well as any attempt at urban renewal. While the building lacks commemorative plaques, it has not been turned into a luxury hotel either, despite such plan being discussed for years.

What is behind this inertia?

"I do not believe the excuse of bureaucratic obstacles and lack of funds", says Mazzucchelli, "given the zeal with which many other buildings have been restored".

Rather, "this inertia reflects the ambivalent attitude of the Serbian elite, who for years have carefully avoided touching such a sensitive and delicate matter, aware of the risks of playing with two narratives hard to reconcile, one that interprets the ruins as a symbol of Milošević's crimes and the much more widespread one which sees them as an act of protest against the West's aggression of Serbia".

Asked if the Generalštab is likely to remain an unresolved space, a 'memory lapse', Mazzucchelli says: "It will remain so until the wars of the 90s find a narrative shared by a large section of the Serbian public. In any case, the idea that the Generalštab could become a luxury hotel makes me uncomfortable, because it would mean to deprive Serbian society not only of one of the most remarkable examples of Yugoslav architecture, but also of a valuable opportunity to create cultural memory”.