Turkish residence permit for foreigners - P.Martino

Still in Van and of Mussa Khan, no news. The journey amongst the Afghan muhajirins continues: trapped in the Turkish city, in the limbo of temporary asylum waiting to continue their journey, even illegally, through Greece and Italy

The Milky Way is the silvery roof of the sleepless upland: at dead of night the alleys of Van keep swarming with discrete trades, while up above, in the pale and distant sky, the light of the stars keeps pulsing coldly.

I give up on the idea of the expedition to Yuksekova: it is complicated and has little chance of success, so I decide to focus on continuing my researches in the city. I spend my whole Sunday in the streets, and together with Shahin we chase suggestions, images, any hint that can lead me on Mussa’s tracks.

We go back to the neighborhoods surrounding the castle, wander in the suburbs and loiter in the otogar, the bus station just outside the city. It is just a failed attempt, though: muhajirins do not leave traces of their presence. The day winds up in front of the computer: no e-mail, no message on Facebook. Mussa has cut off contact with the world.

Early morning on Monday, I meet with Shahin in front of the seat of Maslum Der, the association of solidarity for Van’s refugees. We meet with Fatma, the young woman President. While pouring the unfailing cup of tea, Fatma gives us an outline of the situation.

“There are about 5.000 foreigners, in this city: Afghans, Iranians, Iraqis, Kurds. Some of them just pass through, they stay a few weeks at the most, with no permits. Some others, asylum seekers, wait months for the authorities to decide on their request for international protection. Others still, most of them, are just trapped here. They have been for years. People who are not granted refugee status, youngsters awaiting the appeal verdict, families bound to resettlement in third countries, which never happens”.

The technical language Fatma uses puts a great strain on Shahin’s English. She, however, continues: “Consider that only 2% of Afghans is actually resettled: even when they are granted refugee status, they rarely find countries willing to welcome them. In the West there is a lot of mistrust towards them. That is why there are so many of them in Van. There are over 2.500”. She keeps talking: “They lead hard lives: the Government does not grant work permits to asylum seekers, and they have to pay a high Temporary Residence tax, along with living expenses”.

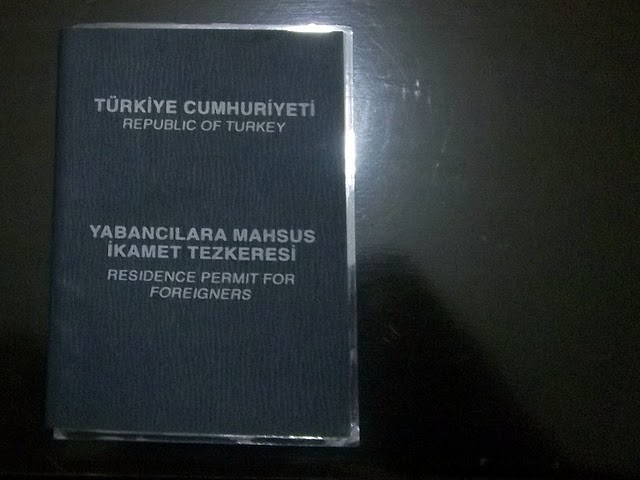

“A Temporary Residence tax for refugees? Is that possible?’ I gesture to Shahin to translate my question. “Yes, it is”, Fatma answers, not even the slightest bit surprised by my reaction. “Three hundred and seventy-five Liras (193 Euros) every six months”. She goes on: “Rents in the city vary from 150 to 350 Liras. We help them by providing blankets, medical assistance, sometimes even food. But we do not have the money to bear these costs, they have to provide for themselves”.

I take a moment to reflect on these data. How much wealth must refugees have saved to get through such a long period in these conditions? How many debts must they incur? Mussa Khan is self-sustained, he travels without any help from his family and does not have a great amount of money saved. If he sought asylum in Turkey, very harsh years would await him.

A young man enters the office. “My name is Naqeeb, welcome to Van”, he says in excellent English, while a smile crosses his face. Fatma talks to Shahin, who then translates: “When I learned that an Italian reporter was interested in the Afghans of Van, I immediately thought of Naqeeb: no one knows the situation better than him!”

Polyglot, adventurous, with a sunny character, Naqeeb arrived in Van in 2008, when he was 25 years-old. Recognized as a refugee in first instance, he has been waiting for two years to be resettled abroad. Meanwhile, he has become a reference point within the local Afghan community and has opened an English evening school for the youngest muhajirins.

He was informed last night that I would be here and he asked the baker, for whom he works under the table, for a half day off. Five hours at the bakery and a shower later, he rushed here. “I have already baked 500 loaves!”, he says amused. He was an IT engineer, back in Afghanistan.

Naqeeb is the person I was looking for. He has a widespread network of contacts: if Mussa is in town, he will surely know where to find him. When the interview is over, we say goodbye to Fatma. We walk down the street, where Naqeeb tells fragments from his story. “After the fall of the Taliban, I went back to Afghanistan and found a job at an American medical association in Asdabad”. There in his hometown, he builds his career: he earns a good living, buys a house and a car, makes plans for the future.

“Things, though, changed quickly: Kunar, on the border with Pakistan, became a very hot zone”. A prominent person, Naqeeb is under threat by the insurgents. “They wanted me to work for them, and not for the Americans”. A first threatening letter does not scare him, not even a second and a third one.

One day, though, his cousin is killed, in front of many, by someone in a running SUV. Naqeeb wants to stay, but his Father obliges him to flee, to disappear from Asdabad for his own sake and for the sake of his family. It was the 20th of September, 2008.

Naqeeb’s words reach my brain like pointed needles. I fret with the wish to ask him about Mussa, but I want to listen to his story, first. “When I got to the Iranian Embassy in Herat, the driver sold me a visa for 1.000 Dollars. Officially, it costs 200 Dollars. At the time money was not a problem for me. And so I left on a plane to Mashad”.

In the streets of Mashad he hears some young men speak Pashtu, his language. They are going to Europe, also. They give him the number of an Iranian smuggler, with whom he meets in a hotel room. In two hours they make a deal: 750 Dollars to get from Mashad to Van, across the Turkish border. Payment on arrival.

What for Naqeeb was supposed to be a brief stay in his journey towards the West, however, turned out to be his prison, even though he was granted refugee status.

“Turkey has applied a geographical limitation on the 1951 Geneva Convention. It only grants asylum to refugees coming from Europe. It allows the rest to only stop temporarily, waiting to be welcomed by third countries”, as Thomas Faustini, office supervisor for the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) in Van, explained to me in the afternoon.

“Of course”, Faustini added, “there are no European refugees, here, so our job is to find welcoming countries for refugees to whom we grant status”.

The UNHCR registered 12 new refugees every day, between April and July 2010. In mid April, 80 Afghan minors knocked on their door, all together. Resettlement procedures though, move at an exasperatingly slow speed.

“Our staff has been reduced, relations with the Turkish government are delicate, the flow of migrants is on the rise. Europe and the United States accept very few refugees. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to do more”.

I meet again with Naqeeb the same evening, in a restaurant in center city. I have been invited to a farewell party of a Kandahar family going to Canada. They had been waiting for resettlement for four years. They all speak perfect Turkish, now. The invitees, approximately 20, are Afghan refugees from different ethnicities: at the same table, Hazaras, Tajiks, Uzbeks and Pashtuns.

At the party, some of the invitees talk to me about their troubles. Ahamad, 22 years-old, and Latifi, 21, friends from childhood, are from Bamian, and they fled Afghanistan on board of a truck. “We have been here for five years, with no work, no university, no documents, no future. The UNHCR has already rejected our first appeal, we have been waiting for the verdict on the second one for a year. For us Pashtuns it is very difficult. They do not even have a mother-tongue interpreter, so we have to manage with Farsi. We often think about continuing our journey, illegally, through Greece and Italy, but smugglers ask for a lot of money. Going back is out of the question: Van is our prison”.

The party continues till late at night, at Naqeeb’s house. Then the hugs, the tears, the wishes for those who are leaving and the sadness for those who are staying. Right in front of my eyes, the verdict from the “resettlement lottery”: few lucky ones are off to a better life, the others remain stuck in the limbo of temporary asylum.

At 3 in the morning I am alone with Naqeeb. I muster my courage: “Listen, Kardash. I am sorry to tell you now, but I am not here to only write a report. I am looking for a friend, and maybe you are the one who can help me find him”.

In the dark of the room, the moments feel endless. “Your friend”, Naqeeb answers, “is also my friend. We will find him. But not now: now it is time to rest. Sleep”.

I smile. I think of how many things have changed during the day that has just gone by. Then I finally drift off to a deep sleep, the way I had not slept in a long time. Outside, the stars of the Milky Way are the same, unchanged, cold and pulsing. For me, though, in Naqeeb’s home, this is my first night as a muhajir.