The ancientVia Egnatia near to Traianoupolis - Fabrizio Polacco

States and Empires on the rise or at the height of their power build roads and bridges, while when in decline or in danger they raise walls and barriers. A journey along the ancient Via Egnatia which connected Italy with ancient Greece, continues as far as Byzantium and now gives its name to a motorway

Anyone who has known Greece for some time can't help but remember it. Crossing the northern part of the country from the Aegean to the Ionian sea was quite an adventure: uphill and downhill for seven or eight hours, with sharp bends and steep slopes on a strip of asphalt clogged with lorries and toiling buses, at times funnelling through picturesque villages and crossing vertiginous mountain passes, finally to embark for Italy from the port of Igoumenitsa, set in an angle under Albania not far from the coast of Apulia.

Now this is all over. One single short tunnel was yet to be completed this summer along the brand new Greek motorway which, with a length of 670 km, makes it possible to cross from one sea to the other in a couple of hours and even reach the border of European Turkey within the same morning. Then from there, if you wish, you can go on to Istanbul, gateway to Asia, and viceversa.

The paradox is that the eastern section, from the town of Alexandroupoli to the Greek-Turkish border at Kipi, is often half empty. It leads, in fact, not only to the barrier between two states which continue to be on bad terms, but also to the extremity of the European Union, marked by the lower River Evros. And this is exactly where the Greek government is building a barrier made up of a barbed wire fence and a deep ditch. The reason for this is to limit the increasing flow of migrants from Asian and African countries who pass through Turkey. They can even be seen as the sun goes down marching in single file in small groups trudging along the hard shoulder of the empty motorway.

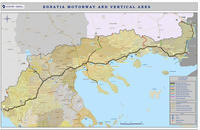

The Egnatia Motorway

The idea of this road link was put forward in the 90s (work began in 1996). With the collapse of the Soviet Union and Turkey moving towards joining the European Union, an intensification of traffic in that direction was expected and the migratory pattern was far from causing the current response. A prestigious name was resuscitated for the work – that of the ancient Via Egnatia. It meant nothing less than the continuation into the Balkans, beyond the Adriatic, of the Romans' regina viarum: the Appian way. This, as is well known, linked the City to the port of Brindisi from where the boats departed to reach the coast of what is now Albania, which is where the Egnazia started, thus connecting Italy with ancient Greece, proceeding to Thessalonica (Salonika) and Byzantium (Istanbul). From here the armies, administrators and merchants pushed on towards the provinces of Greek Asia and its great emporiums where even caravans from the most distant Orient would arrive.

The Egnatia was so important as to be the first of the many roads the Romans decided to build outside the Italian peninsula. It was, for those times, an extraordinary feat: crossing the Balkans from East to West at that latitude is in fact a challenge to a mountain system. Already in itself the term “Balkans” means mountains but, to add to this, in these regions the relief, including the main rivers, is structured on north-south lines, so the Egnatia had to cross them all. Only the organization and financial means of the greatest empire in classical antiquity could accomplish that 1,120 km long road paved in stone, far longer than today's motorway, the Eghnatia Odòs, as the Greeks call it.

The Romans were well known for building roads and they worked so well, with the perspective of their roads lasting for centuries, that stretches of the ancient route are still existent, as I found in several places: for instance behind Kavala, a Macedonian town wedged in the mountains and overlooking the shimmering Aegean sea with its constant ferries crossing to the islands. This part is very steep since the road climbed and then dropped over the pass above the town on the way from the nearby Philippi. Yes, the site of the battle which Octavius and Anthony won against Julius Caesar' assassins and also that which inspired St Paul's “Letters to the Phillipines” as he, among many, passed through it on his journey to Rome.

The ancient Egnatia way, the bipolar road

The modern road structure is also an engineering marvel, as the figures alone show: 177 big bridges, for a total of 40 km, besides 73 long tunnels (the biggest being 4.8 km long). Especially in the stretch near Epirus, where 30% of the road is well above or below the level of the land.

Today, as then – in the 21st century as in the 2nd B.C – a small state on its own with limited resources would never have managed it. In fact, of the total cost of approximately 6 billion Euro, half came from European Union funding, as they never fail to remind tourists whose bored gaze takes in the hoardings suspended along the mountain roadsides. Cyclopic enterprises always have broad state backing, or else that of a great union of states, like the one on our Continent, at least as long as it lasts. Even the modern operation, like the one directed by the Consul Gnaeus Egnatius after 146 B.C, had a grandiose ambition: to connect the two parts of the world rapidly and safely. The Via Egnatia after all was, and is, with its size and its cost, a road whose sense must be bipolar. Then the poles were the political heads of the two parts of that vast empire: the Western, with its capital in Rome, and the Eastern, with its capital in Constantinople. And today?

The new Via Egnatia, the suspended road

Today this superb ribbon of asphalt is in danger of becoming a magnificent suspended bridge, its final spans missing. At its extremities do not await open passageways in fact, but the indecision, slowness, short-sightedness and disputes which divide the governments of the region. This doesn't mean only the variable relations between Europe and Turkey. Even the Western part of the Egnatia, compared with the Roman road, reveals elements of present geopolitics. In fact the old road did not leave from Igoumenitsa or cross the Southern Epirus – the Romans knew that the shortest sea route between Brindisi and the Balkans was not there, but further North, at the port of Apollonia and, even further North, Durrës offered an easy access to the Balkans. So they made their road start from these two towns which were then Greek, inhabited by Greeks, whereas now they are Albanian. From there, the Egnatia Way proceeded to Salonika in Greece, crossing the territory of the Macedonian Republic or FYROM, depending on one's point of view, where it touched Lake Ochrid and Erakleia Lynkestis, today Bitola. After all, if the original logic and route had been respected, the new Egnatia would today have crossed four countries (Albania, Macedonia/FYROM, Greece and Turkey), not just one.

However, perhaps it was to be expected that, together with the European funds, Greece would also acquire the name of the prestigious Roman road for this worthy deed. To be or not to be in the European Union: this also makes a difference, particularly in the field of infrastructures.

The ancient roadway of Suleiman the Magnificent

But if in its first part the modern Egnatia has changed its course, and the last part remains without great outlets, what happened to that part of the Roman way which reached Imperial Constantinople? It crossed the present Greece-Turkey border (the one that today is intended to be “fortified” with a barrier) just below the customs station at Kipi, near the ancient Traianoupolis, where it is visible for considerable stretches even though it has lost its stone surface. On reaching the Sea of Marmara the ancient Way followed the coast until it emerged in the city, par excellence, through the “Golden Gate” - an opening in the magnificent wall of the Oriental capital.

In effect, even during the age of Byzantium and the Ottomans, the Egnatia Way continued to function, partially: to be used by merchants, armies, wayfarers, preachers, crusaders, invaders, explorers, migrants and fugitives, in both directions. But since over that long millennium East and West were almost always opposed to each other, from being “bipolar” it became one way. That is, its traffic flowed outwards from the capital. In those days it was the salt waters of the Adriatic, not the fresh waters of the Evros, which constituted a physical boundary.

The Christian Emperors and Muslim Padishahs continued to repair and use it. However, while Byzantium was in decline and saw it more as a possible opening for invaders, the Ottoman Empire in its golden years, particularly in the time of Suleiman the Magnificent, considered it one of the two “wings” which enabled it to fly from the capital to the two extremes of the world or, more exactly, the Western wing which connected it with its subjugated people in the Balkans, and would sooner or later, they hoped, have conveyed the armies of the half moon to conquer Vienna.

The stone bridge with 28 arches

Someone leaving Istanbul today, passing the Ataturk airport, going along the coast, follows a wide, busy, modern road more or less on the traces of the Via Egnatia. At a certain point, however, a broad lagoon flowing into the sea is encountered, which the ancient Roman road passed inland. The Sultans, not tolerating such a deviation at the gates to the capital, decided a bridge should be built there, cutting through the lagoon in a straight line. Thus, anyone coming to the town of Büyükçekmece for the first time, can appreciate an extraordinary feat of engineering, which is also one of the artistic masterpieces of Ottoman Turkey, and which, perfectly restored about fifteen years ago, still functions even now. In fact, the 636 metre long bridge crossing the lagoon, is as unusual as it is practical. It is supported by 28 vaulted arches, divided into 4 sections, each being built in the form of a “donkey's back”. So, although it is quite wide and imposing, it seems to wind away in a narrow and willowy line. It is the work of the famous Ottoman architect Sinan, who wanted it built completely in a stone of a soft, warm tint, almost pink, in daylight.

I crossed it on foot (luckily it's closed to traffic) at its most luminous time, with the sun vertically overhead, in late August, made tolerable by the fresh wind which blows in constantly from the Black Sea.

The local people still use the bridge nowadays, in preference to the road below with its chaotic traffic, to cross between the two parts of the town separated by the lagoon - even the clerk in jacket and tie, who takes it at a fast pace with a briefcase full of white documents under his arm, on his way back to the office. He notes me as a foreigner, maybe because of the camera, and decides with the kind manners of small town Turks, to do me the honours of the house. Together we reach the town hall where he works – and there he fills me with photos, posters and illustrated volumes about this beautiful and little-known suburb of Istanbul.

When I take my leave I continue, slightly dazed by the sun, to wander towards the port of Büyükçekmece. It is now three in the afternoon and, partly due to Ramadan, I have neither eaten nor drunk anything. I should try for some refreshment but my eye is attracted by the shady entrance to the small council library still open to the public. I decide to enter, hoping to find out how to conclude my long journey along the Egnatia with a special excursion.

Bridges or walls?

States and Empires while on the rise or at the height of their power build roads and bridges, while when in decline or in danger they raise walls and barriers. And I've read somewhere that a Byzantine Emperor, as the pars occidentalis crumbled under the invaders' blows, had wanted to erect an insurmountable barrier to separate Constantinople from the rest of the Balkans. The mighty double Theodosian walls we can still see encircling the city were not enough. With a 56 km long wall, he wanted to separate the whole peninsular with its capital on the waters of the Bosphorus , from the rest of the continent (today called the peninsular of Catalça). The trouble is that no-one knows or remembers anything about this wall. All those I asked had never heard of it, and even detailed maps showed no trace, nor could I find any road signs. And yet, after Hadrian's Wall in Britain, this was supposed to be the longest continuous wall built in Europe by ancient Rome!

The Vallum Anastasianum? Never heard of it

Even the kind librarian I consulted, on hearing my request, disconsolate with arms outspread said, “The Vallum Anastasianum? Never heard of it.” Guided by experience or some sixth sense though, she placed on the wooden table two large books never seen before, as they'd been published by small municipalities on the peninsular. And that is where I found the first picture: a photograph yellowed with age with subtitles describing the ancient wall and even the present day villages that are on its course. But it added, alas, that over the centuries the local people had removed most of its stones to build their houses with them. So I learned that the Wall started at the ancient Greek colony of Selimbria, on the Sea of Marmara, about thirty kilometres beyond Büyükçekmece, cutting the Catalça peninsular in two, and arriving at the Black Sea at the opposite end. Fortunately it seems that on that side some trace remains - at the tiny Turkish village of Karacaköy, to be precise. That's where I must go, I tell my interlocutor, to find what's left of this colossal work which, among other things, completely contradicted the sense of the Via Egnazia, breaking its route near Selimbria.

I left the librarian, thanking her for two formidable cups of tea, nearly as thick as honey, which gave me the strength to go on, and headed for Selymbria, today known as Silivri. It is an explosion of life, full of movement, young and densely populated. From its Acropolis, half the Sea of Marmara can be seen. Not for nothing, the Greeks founded it even before Byzantium. No sign of the Wall there, but I already know as I admire its shores and waters that tomorrow will find me on the ones opposite, on the Black Sea.

That is how the following day, with a Turkish friend, I reach the remote village of Karacaköy. Here the men in the square know about the Wall and give us the right directions. It's a few kilometres away, towards the sea. We get there by car along a narrow, deserted strip of asphalt and, finally, on our left in the shadow of the vegetation, and even trees which have grown over it, is the barrier which was to save Byzantium. It's in ruins, the roots of the plants in places split its line of rectangular stones but still reveal a magnificent past. History has shown, however, that the Wall was soon ineffective considering the reasons why it had been built. The invaders always find a place to get through, as aspirations for improvement and decline at their origins,push stronger than the barriers manage to block. So it was abandoned. Local people dismantled it to make their buildings, and no one took any further interest.

Facing the cold, agitated waves of the Black Sea, which reflect the clouds dragged rapidly over them by the wind, I think of all the bridges, the traces of roads, the passages and flyovers that I've seen in these weeks of pilgrimage along the Egnatia, and I compare them with their poor remains. The centuries and millenniums finish sooner or later by rendering barriers void of meaning and surpassed. But men, whatever civilisation they belong to, always rebuilt their roads and bridges proudly, which must mean something after all.