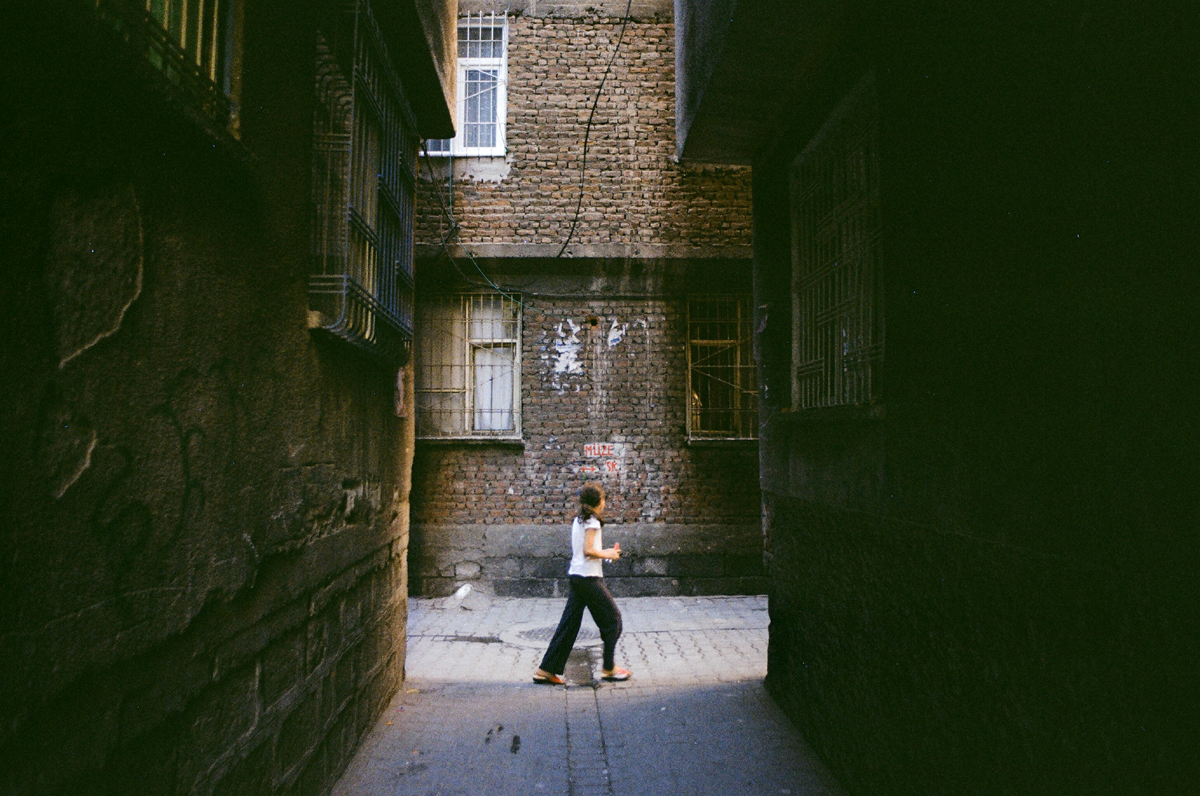

Diyarbakır's old town - ph. Francesco Brusa

"We have always valued hope over victory. Now, however, we are winning some of our battles". An interview with Ceren Karlıdaĝ, journalist, feminist, among the protagonists of the magazine Sujin Gazete.

We met Ceren Karlıdaĝ in Diyarbakır, "capital" of the Kurdish-majority region of Turkey and theatre of some of the most violent clashes between the Turkish state and the PKK, as well as of the bombings of the Old Town ("Sur") that have changed the place and the life of its residents forever. Here, Ceren and her comrades created Sujin Gazete , a press agency and journalism site made exclusively by women, recently blocked by the government through decrees issued under emergency conditions.

Sujin Gazete is an explicitly feminist journalist collective. What does it mean to be a feminist in a context like the one you live in?

Feminism, understood as a movement that historically developed in Europe and the "Western" countries, is something that we perceive ideologically very close to us. Yet, finding ourselves in the Middle Eastern context, we had to reinterpret it. In general, it seems that too often feminist discussions are locked up in an excessively elitist or academic sphere and end up having little grasp of reality. For us, however, it is imperative to start from this assumption: feminism is the first "women's rebellion" in history, i.e. it is imperative to develop an awareness of how women have been and still are oppressed subjects.

Our main ideology is jineology ["Jin" means "woman" in Kurdish], a line of thought developed by Abdullah Öcalan, that is now playing a key role in the Rojava revolution. In my view, jineology builds upon – and discards – today's feminism in two main directions: a more holistic approach to the sphere of social sciences, and a more pertinent connection to the daily life of the Kurdish population. We believe that dominant masculinity is an essentially destructive mentality, in both material – with acts of violence against women's bodies, the environment, etc. – and symbolic terms – with the division of theories, even alternative or dissident ones, in different streams that do not communicate with each other (as for the case of feminism itself). Jineology strives to be as inclusive as possible while attempting to dismantle the dominant ideology in all its aspects.

How can these principles be put into practice?

When speaking of Kurdistan, we must keep in mind that we speak of four different contexts, and each of them is or was a colonised territory. Especially in Syria and here in Turkey, Kurds and women were excluded from social participation. A "female" revolution, such as Rojava's, is not something that happens overnight, but it is a long process, prepared by 30 years of struggle and self-organisation. Here, one of the primary needs for women has been to look for spaces of autonomy and freedom, where they could try to think outside the canons of "masculinity". This has produced several "break-ups" with the existing institutions – women have created their own army, associations, political parties.

Finally, in Rojava, thanks to a more active participation of women in political life, new government systems are being created. The whole world is looking with interest at our co-presidential mechanism, by which a man and a woman lead the administration of districts and cities. Then there are women-only courts ruling on cases of violence against women, and women's parliamentary assemblies are emerging to remedy the fact that men always decide on every area of women's life (politics, work, childcare, etc.). Indeed, one of the main effects of these political changes is the birth of a new "female" economy: workshops and cooperatives are opening where women work autonomously. In general, we try to pursue the ideal of a hierarchy-free life in all relationships (man/woman, father/son, wife/husband...).

What about journalism?

Women's entry into the world of journalism certainly fits into the parable that I have just described – I am mainly referring to Turkish Kurdistan now. Seeking space for autonomy and freedom, women have also turned to the field of information, traditionally dominated by men. Things have particularly changed since the late 1990s, with figures such as Gurbelli Ersöz, who became Kurdistan's first female editor-in-chief.

We, as Sujin Gazete, feel like we have inherited those experiences. In 2012, we founded the Jinha press agency with the precise intent of breaking and reinterpreting the dominant male mentality in the media. It was an independent, women-only press agency that focused not only on the Kurdish women's liberation movement, but also, more generally, on the feminist movement in other parts of the world – doing it in the most professional, active way as possible. The website was updated daily and we always provided insights, interviews, or reportages, as well as news.

Two years ago, when the conflict between the AKP and the Kurdish people broke out again, our journalists were on the field to tell the truth about all that was happening. Many of our collaborators have been arrested, some reports have lead to actual trials, and now the government has also blocked the access to our page, that can no longer be updated.

Journalism is often seen as a "male profession", because it requires technical skills and because, in general, we tend not to give credit to what a woman says. However, we should not interpret our activity simply as women entering the media field – it would be too much of a limited perspective. In fact, I believe that our job is to show how violence against women fits into a precise system of hierarchies.

Can you go into detail about this aspect?

When a rape or femicide occurs, it does not just mean that a man attacked his wife (or girlfriend, sister, etc.) out of a fit of rage. This rage is part of a wider system and is in some way supported by the state, which through its oppression urges men to unload their frustrations on women.

I would like to point out that it is in these very areas of Mesopotamia that the first matriarchal societies were born, which saw the woman as a goddess. A breakthrough came with Sumerian civilisation and the development of religion, which joined the state to form the chain of oppression that I mentioned. I speak of a true hierarchy: God (that remains a creation of men) stands above the state, which cannot violate divine precepts; men are beneath the state, that uses God to control them; men oppress women, relying on the principles emanating from religion and government – and so on, creating a "society of fear". It is symptomatic, therefore, that even sacred imagination shifted from the Woman as Goddess to the Madonna, whose only reaction to injustice is to weep.

That is why the Rojava revolution and women's struggles in Turkish Kurdistan also have a great symbolic value – a sort of "archaeological excavation" to find the "goddess spirit" that was born in the area and was suppressed for thousands of years.

Do you think that religion is antithetical to the women's struggles in the area?

I think that, originally, Islam had introduced principles of behaviour positive for women. However, it has never gone through any process of reform or renewal. There are of course attempts, both individual and collective – for example, the HDP recently organised a Congress of Democratic Islam , where self-defined Muslim women discussed a possible alternative Qur'anic interpretation.

Probably, however, this is not the point. The point is that religion ceases to be an obstacle or an advantage when there is a project of liberation transcending differences and particularisms. This is what is happening in Rojava, where there are not just Muslims and there are not just Kurds. There is, instead, a common political project which finds its main value in the union of different struggles and perspectives.

As Kurdish women and men, we have always valued hope over victory, but now we are beginning to win our battles. And I believe, on the basis of these achievements and the consensus they are gathering around the world, that the 21st century will truly be the century of women!

This publication has been produced within the project European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page