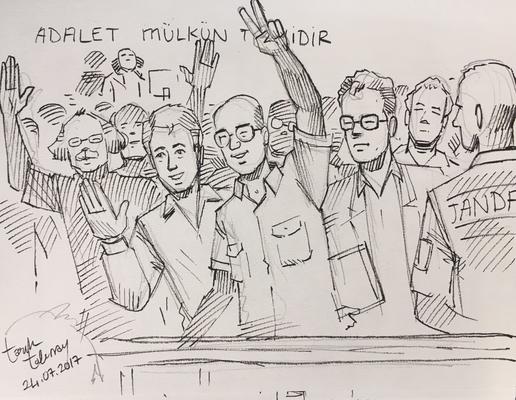

Drawings made in the court during the trial © Murat Başol

The trial has started in Istanbul for Cumhuriyet journalists and administrators, accused of terrorism. The voices from the courtroom in the debate symbol of the concerning state of relationships between journalism and power in Turkey

The trial of journalists and administrators of the Cumhuriyet daily, which started on July 24th, is emblematic of how tense and grim the relationship between journalism and power in today's Turkey is.

The 17 defendants waited in prison for nine months for the trial to start – a time that they defined as a punishment before the verdict. They are all accused of supporting armed terrorist organisations without being members; some are accused of association with and management of a terrorist organisation.

In detail, the newspaper and the Yenigün Foundation, which funds it and owns the trademark, are accused of funding terrorist organisations and illegally changing the editorial line to support them. These are the Pkk (Armed Forces of Kurdistan Workers), Pyd (the political organisation of Syrian Kurds close to Pkk), Dhkp-c (left-wing Leninist armed group), and Fetö (an acronym coined by the government to refer to the network of Imam Gülen, accused of the attempted coup of July 2016). These organisations can hardly be put under the same umbrella, but the prosecution frequently cites them together and indifferently. This is because the government sees in them a common purpose – the destruction of the Turkish government and state.

Mustafa Kemal Güngör, attorney and member of the Board of Directors of the Yenigün Foundation, gave an emblematic testimony: "When I was jailed for the first time, the guard who registered me asked me why I was there. I answered, Fetö and Pkk. He looked at me incredulously: 'Both of them?'. In the end, he only wrote Fetö".

Journalism or terrorism

The trial is based on the core allegation of changing the editorial line for terrorist purposes. According to the prosecution, this had been the purpose of appointing Can Dündar as chief editor of the newspaper, after the composition of the executive board of the foundation had been forcefully modified – allegedly – through the removal of unwelcome members. The Board of Directors of the Yenigün Foundation allegedly played a key role in this process.

According to the prosecution, Mustafa Balbay is among the excluded. The defense argues that, according to the statute of the newspaper, it is not possible to be a political candidate and at the same time part of the board of directors, so Balbay was dismissed from office after a vote. Balbay was elected in the ranks of the Republican Party CHP.

The dismissal is seen by the prosecution as a sign of manipulation of the newspaper's editorial line. Balbay later tweeted that "Cumhuriyet welcomes Fetö or Pkk members, but not CHP MPs". The tweet was used as evidence. Yet, a signature indicates that Balbay was among those who supported Dündar as head of the newspaper.

Journalist Güray Öz is also accused of influencing this vote. Yet, he says, "I was not even present at the board when Balbay was removed".

Kadri Gürsel, another journalist and defendant, says: "I am accused of being part of the board, but I am only a consultant and I have never had any decision-making power, contrary to what the indictment says".

The testimony of Akin Atalay, among the newspaper's founders, adds further details about the disputed elections: "In the election of the board, the prosecution argues that if a candidate, who was defeated, had been actually elected, this would have prevented the publication of pro-terrorist articles. This accusation is the only justification for which we are here today, otherwise this matter would be the responsibility of an administrative court. Prosecutors feared that, if they did not add this accusation of terrorism to the charges, they would be labelled as Fetö supporters themselves".

Investigative journalism and journalism under investigation

The changes to the editorial line, therefore, allegedly led to the publication of articles aimed at putting the government in a bad light and facilitating the propaganda of terrorist organisations.

Journalist Mehmet Sabuncu defends himself: "I am accused of supporting, through my articles, the corruption scandal of December 17th [2013, which involved government ministers and also caught up with Erdoğan and his family]. I'm a journalist, how could I avoid writing about it? Indeed, if journalism were allowed to investigate adequately in that case, perhaps the current situation in Turkey would be very different”.

"My article of July 31st, 2015, titled 'Peace at Home, Peace in the World' [a motto tied to Kemalism, ed.] is presented as evidence. But the indictment states that the coup plans were prepared on November 9th of the same year. So, were we ahead of those who plotted the coup?".

"Another article of mine is titled 'Danger in the Streets' and is seen by the prosecution as an attempt to polarise society, stirring up hate. And yet, the prosecutor did not even bother to read the first two lines of the text, where I call attention to provocative acts at a time when people are taking to the streets to defend democracy. Newspapers like Star [close to the government, ed.] came out with titles identical to ours, yet they are not on trial", Sabuncu concludes.

"I am here because I have been faithful to the principles of journalism, I denounced Fetö and its alliance with the government, that I had even warned about the danger of cooperating with such an organisation. My forecasts have come true", said Kadri Gürsel.

Many defenders have complained that the indictment is based on the use of articles and editorials of newspapers known to be close to the government. This, combined with the fact that Cumhuriyet's journalists and administrators are on trial for the newspaper's articles, titles, and tweets, have made "all this a trial of journalism itself", argues defense lawyer Fiket Filiz.

Affiliation charges and the Bylock application

According to the prosecution, journalists and executive members of Cumhuriyet undertook all of this because they were affiliated with terrorist organisations. In particular, charges are based on personal relationships with (other) members of Gülen's network and the use of the Bylock smartphone application, which according to the authorities was used for some time by the network for coordination.

But Kadri Gürsel replies: "I was accused of being a terrorist because I received texts from people who had used Bylock. I have never answered any of them. Unidirectional communication cannot be used as evidence of correspondence. If prosecutors did not see the inconsistency of such evidence, they failed in their duty. If they have seen it and yet insist on their allegations, it means they are abusing their position”.

"I was accused of having contacts with 13 alleged members of the organisation on an estimated total of 215,092 alleged users of Bylock. I am a journalist, I am free to contact any source of information", Mehmet Sabuncu says.

"How do you know if someone who contacts you has installed Bylock on their phone or not?", asks rhetorically Mustafa Kemal Güngör. "I do not remember much of these texts, but if the prosecution considers them criminal in nature, the burden of proof is on them".

In addition, according to the authorities, there are still thousands of suspect communications linked to Bylock waiting to be decrypted.

Bülent Utku believes that "consequently, anyone of us may have had a phone contact with a user, yet the legal criteria for which Bylock users are considered criminals are still vague and unconvincing. How can you effectively defend yourself from this kind of charges?".

Güray Öz's bitter reply is: "The phone call that connects me to Fetö is a call to an Ankara restaurant to order food".

Akın Atalay's account of the trial creates a disturbing picture: "This case was not built on evidence, but on the desperate attempt to make up a network of alleged relationships by digging in the personal lives of the defendants, but also of their relatives, friends, grand-grandchildren, and even ex-wives of twenty years before. My telephone conversations over the past 5 years were analysed. In this period of time, it turns out, I have come into contact with five Bylock users and with six individuals linked to Fetö. Everything is built on random circumstances. We should also check the prosecutor's tabs. To date, it turns out that at least one prosecutor out of four had links to Fetö. It is very likely that, using this absurd method, the tabs of the prosecutor charging me look far more suspect than mine".

Atalay also explains how he was accused of affiliation with the Pkk: "For one year I had professional contacts with Erol Dora (now involved in another anti-terrorism investigation), formerly a press agency employee and elected for the HDP in 2015. Erol allegedly transferred a suspect sum of money to Pervin Buldan (HDP member) and for this he has been labelled as a PKK affiliate. Consequently, the prosecutor believes I am one too".

Bank accounts under scrutiny

Even journalists' bank accounts have been sifted. The prosecution believes that some money transfers are indicative of the criminal connections of the accused.

Önder Çelik says: "One of the financial transitions under accusation is a 300-lira payment for my car repair. The mechanic's bank account was in the name of his wife, who had worked for a company suspected of helping Fetö two years earlier".

Akın Atalay, instead, allegedly made a payment for a 2,500-lira floor carpentry work. The carpenter's son, named Atilla, apparently made a second payment to a company suspected of being part of Gülen's network. The prosecutor, therefore, linked Atalay to the Gülenist company through Atilla. This appears to be how the charges were made.

Cumhuriyet's financial movements

Yenigün, the foundation that supports the newspaper, is accused of establishing business relations with actors close to Fetö to deal with financial distress.

The defense denied these financial difficulties, pointing out that there are no ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, wages are regularly paid, publications proceed, and there are no claims from creditors. The prosecution challenges the sale of some properties for the purpose of extinguishing past debts, because the amounts would be out of market trends, but – according to the defense – these were certified by the relevant state agency. "If the deals are fraudulent, why is the person who certified the operation not on trial too?", ask lawyers. "In any case, these are financial crimes that have nothing to do with terrorism and are therefore outside the jurisdiction of the criminal court conducting the trial".

Akın Atalay points out that "the newspaper is also accused of suspicious financial transactions, for a total of 170,000 lira out of a total of 230 millions. These are regular payouts to press agencies (Cihan Haber) which all media were using, or payments for adverts (Bank Asya via Kaynak Medya) that the newspaper accepted five times, while other media outlets accepted hundreds. Now, these companies turned out to be part of the Gülen network, and therefore this newspaper is accused of being part of the congregation as well.

Attorneys and experts under accusation

To defense raises two challenges to the charges.

The first concerns the prosecutors of the Republic. The case against Cumhuriyet was initiated by Murat Inam, prosecutor in charge of investigations, who is now on trial for affiliation with Gülen and falsification of previous investigations. All the defense, therefore, insists on the illegitimacy of a trial started by a prosecutor charged, but not condemned, for terrorist association. After the dismissal of Inam, the prosecutors in charge of the indictment are Mehmet Akif Ekinci and Yasemin Bal: again, according to the defense, this change would be unusual and suspicious in the framework of Turkish case law.

The defense also challenges the selection of the three experts called in by the prosecution to back the charges. Two of them are Ünal Aldemir and Abdullah Çiftçi: the former has dealt with IT sources available to the public, the latter with the election of the board of directors of the foundation supporting Cumhuriyet.

According to the defense, both were selected outside the lists established by the Criminal Procedure Code. If experts can indeed be selected outside the lists in special, motivated cases, the prosecutor has however failed to produce any justification so far.

The third expert, who has assessed the existence of financial crimes, remains anonymous despite the demands of the defense. The prosecution justifies anonymity with protection from external pressures, but – as the defense pointed out – the reports have now been drafted and delivered to the court, therefore such a danger no longer exists.

Akın Atalay adds that "in the case of the digital information expert, who managed to produce a complete report in just ten days, not only does his name not appear on the lists that the prosecutor should draw from, but he is also a volunteer at a think-tank close to the government. In his report, he freely selected excerpts from the newspaper to build a fictional, convenient narrative, without ever mentioning how the newspaper repeatedly condemned the military coup attempt".

Journalist Mehmet Sabuncu concludes: "Once Cumhuriyet journalists are rehabilitated, this trial will go down in history as a crucial step towards the abolition of self-censorship". According to the journalists on trial, what is at stake is an attempt by the central power to intimidate the entire opposition journalism.

The Cumhuriyet trial will continue in the next few days with other defense interventions and questions from magistrates.

This publication has been produced within the project European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page