Turkey is preparing for the parliamentary and presidential elections of June 24 with the new constitutional asset pushed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. We analyzed the situation on the eve of the vote with the constitutional law lecturer Fikret Erkut Emcioğlu

Fikret Erkut Emcioğlu is a constitutional law lecturer at the Okan Universitesi in Istanbul, a senior analyst for the European Stability Initiative (ESI), and an editorial board member at Turkish Policy Quarterly. We interviewed him on the eve of the political and presidential elections in Turkey, scheduled for the 24th of June.

As an experienced lecturer in constitutional law, how do you assess the new amendments to the electoral law?

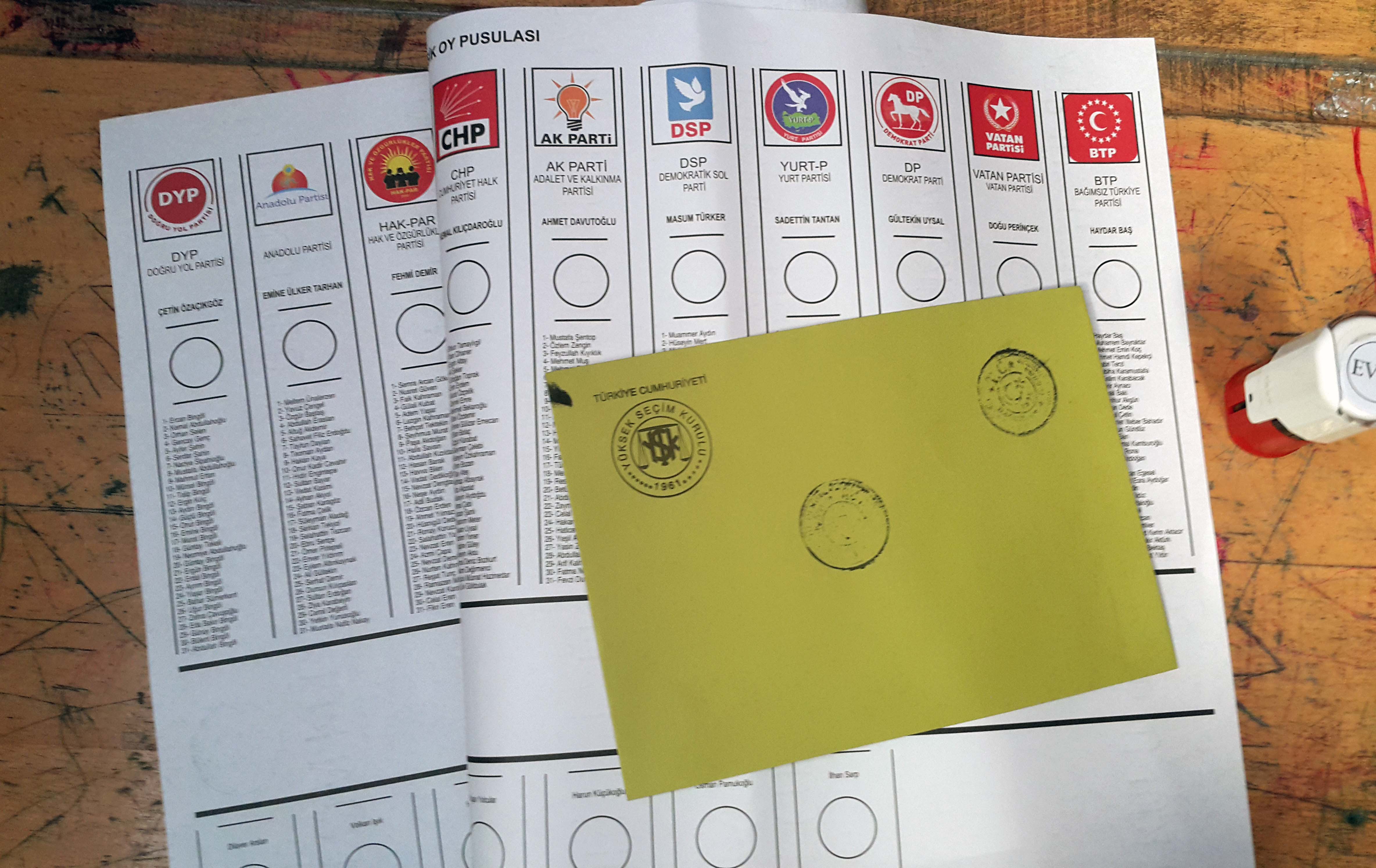

First, we need to determine whether these are real changes, and I don't think so. In Turkey we have seen in the past decades “pre-electoral cooperation” between political parties – small parties getting in the lists of big ones to have their representatives elected to the parliament. We have always heard that there were envelopes without the stamp of the elections board being validated afterwards. We have always witnessed the presence of security forces around the polling stations under martial rule or state of emergency. And one shall not forget that half of the Turkish Republic's lifetime passed under martial rule or state of emergency. These three concerns are not new to us.

However, we should look at the new changes in the system, because they reflect the direction the current government wants to give Turkey. In order to classify a system as a democratic system, you should look neither at the government nor at the legislative powers, but rather at the judiciary. Is the judiciary independent and impartial? This is the main question. The new “executive presidency” government system adopted by a referendum in April 2017 has huge flaws in terms of independence of the judiciary. This concern has always been present since the early days of the Republic. It's not something new in Turkey, but the new constitutional set-up does not remedy it.

We now have a president of the Republic with the power to appoint ministers, all the high-rank civil servants and ambassadors; to reshape the administrative structure of the country; to declare a state of emergency; to dissolve the parliament and call for new elections; and to “legislate” through presidential decrees even in the fields of social and economic rights. This is an important concentration of powers that has no equal in any other system: neither the American nor the French president is that powerful.

Mustafa Şentop, a prominent AKP lawmaker and father of the constitutional reform, claimed it was necessary to eradicate the means of control that Western powers exercise over countries like Turkey, thanks to constitution charts written during the Cold War. This new system is claimed to lead to more independence...

Since 1982, the Turkish constitution has been modified several times. Out of 177 articles, 119 were changed. This means that almost 3/5 of the constitution has been reviewed.

It was drafted under the military rule. However, the 1982 constitution partly incorporated a system that had already been in place since the 1961 constitution, which established the National Security Council, the Constitutional Court, the High Council of judges and prosecutors, and the Supreme election council. The Turkish armed forces were involved in the process of selection and appointment of members to these institutions. The 1982 Constitution strengthened the military implication in the state’s civilian institutions.

The reforms, needed to reduce the influence of the army over the political and civilian life, were undertaken by successive governments in the 2000s, mostly under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). This process was slowed down as of 2011 and halted in 2013, following the Gezi protests and the corruption charges against Erdogan, that AKP rulers regard as a plot by the members of the now outlawed Gülen movement.

Instead, the changes that occurred since and after 2013 have not improved the civilians' life in the country. As I said before, the independence of the judiciary has always been threatened in Turkey by those who really hold the power, be it the Kemalists, Gülenists, or any other influential group. Today, with the new government system, the president appoints directly or indirectly almost all the members of the Constitutional court as well as the Council of judges and prosecutors, in charge of appointing, promoting, and dismissing judges and prosecutors in the country.

One of the issues in the current campaign is the ownership of the Turkish media outlets, believed to be under near complete control of government-friendly business groups. This affects both the electoral campaign and the exercise of the civil and political rights by citizens...

The concentration of the media outlets in the hand of pro-government businessmen is not something new in Turkey. Back in the 1990s, Aydın Doğan bought several media outlets including the daily Hürriyet and I recall that a huge public outcry followed, claiming that this would allow the then government to control the media in Turkey.

Today, Doğan sold its media outlets to the Demirören group, considered close to Erdoğan and the AKP. Business-wise, it may be a clever move by Doğan, threatened by the government due to some unpaid tax issues. It may also be a clever commercial move on the side of Demirören. The real problem is that some groups obtained a quite large part on the media market. However, the Competition Board does not see any risk of abuse of dominant position in that. Questions arise around the independence of this autonomous regulatory body, as the appointments to its board are made by the government. In a system where the government has an appointment power to institutions like the Competition Board or the Constitutional Court, it is hard to imagine them going against its will.

Some analysts argue that Turkey is heading toward a two-party system, thanks to the alliances that the parties formed ahead of the snap elections on June 24th...

In Turkey, we have a proportional representation system that does not allow a two-party system, despite the presence of a 10% threshold. Seeing a two-party system now is even more unlikely, as the alliances actually allow almost all small parties to get seats in the parliament. We can say that the new law on electoral alliances helps to create two poles, but not a system with two parties. Today we have two political poles: on the one hand the AKP’s alliance with the Nationalist Action Party (MHP), on the other hand the alliance between the Kemalist centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP), nationalist Good Party (IYI), and islamist Felicity Party (SP). The pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) is a third actor on its own.

The real game-changer would have been the removal of the 10% threshold, but parties found a way to overcome this problem through alliances. At the end of the day, we may have up to eight parties in parliament: three in one alliance (AKP, MHP, and some names from the Islamist-nationalist Great Union Party-BBP included in the AKP lists) and four in the other (IYI, CHP, SP, and some names from the Democratic Party-DP included in the CHP lists), plus the HDP. However, no obligation binds them to act together after the elections – they just signed protocols that they can abandon right after!

What is the general mood of the country approaching the June 24th elections?

Between 2003 and 2009, Turkey went through an exceptional period in which we felt the possibility to overcome issues that had affected us for decades. I see a breaking point in 2008. Until then, the AKP was defined as a conservative non-nationalist party. In 2007, a “liberal” constitution drafted by Professor Ergun Özbudun’s team on behalf of the AKP was sharply rejected by the opposition parties. Then, right after the closure of the case against the AKP, the party adopted a defence line against the traditional power-holders: military, Kemalist bureaucracy, and academia.

Nowadays, all parties suffer from nationalism. It seems that the real winner is nationalist MHP’s leader Devlet Bahçeli: although his party lost a big part of its support in voting intentions following the creation of the IYI by MHP dissidents, his ideas are endorsed in various fields by the AKP leadership. Bahçeli’s political discourse (his historical references, the threats and fears he often expresses) is now voiced by President Erdoğan. Today, Bahçeli’s views have a radical impact on Turkey’s political and diplomatic choices.

A final remark about the opposition’s alliance: the views of the MHP dissidents that recently set up the IYI do not diverge in essence from those of their former MHP comrades. They differ from MHP’s positions neither on the Kurdish issue nor on any security-related issue. So, in a way, the MHP is within both alliances. The only outsider, the HDP, is also problematic since it was initially conceived as a Kurdish political movement in Turkey and is still defined as such by a large part of the Kurdish (and also non-Kurdish) population. The whole country is unfortunately trapped in a nationalist paradigm, with no real alternatives offered.

These consultations will also elect the next president and new names came to the scene to challenge Erdoğan's rule...

Meral Akşener is one of them, but she's not new to politics. She was Minister of Interior in the 1990s, the years of bloodshed in south-east Turkey, and she's a known as “Asena”, the female grey wolf symbol of Turkish ultra-nationalism.

Another key IYI personality, Koray Aydin, in charge of the party’s central and provincial organisation, is a hard-core nationalist brought up inside the MHP’s youth branches. The reality is that Akşener gained popularity because opposition voters started comparing her with CHP chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who is considered to be too soft, while Akşener is seen as a real fighter.

Lately, the CHP announced that Muharrem Ince will run for presidency as CHP candidate. Ince is also known as a real fighter: he comes from Anatolia, he speaks “the language of the ordinary people”, he is good in polemics, he is neither Alevi nor Kurdish – something that unfortunately still matters in Turkish politics. Yet, he is also well seen by Kurds, since he voted against lifting immunities of HDP lawmakers in the parliament – one of the few from CHP. I believe he has an attractive profile for many voters.

Is there any real challenge to the AKP's dominance over the Turkish political Islam?

The topic of the AKP dominating the entire conservative camp would deserve an entire book itself. I believe the candidacy of Abdullah Gül (an AKP founder and former president of the Republic) would have been a game-changer, but he didn't put himself forward, so I would not comment on him too much. All I can say is that Gül is a very careful politician and he would not have let his name circulate for so long if he hadn't been really considering to run. His main flaw seems to be a lack of, I would say, “bravery”... he did not get on the stage at the right moment.

What is missing in Turkey's political landscape?

We need a party with a strong pro-European, democratic agenda, backed by the pro-Turkish groups in Europe. The CHP has never been a real liberal party, although I see efforts by the current leadership to update the party’s policies in a more liberal sense.

The HDP, categorised from the start as an ethnic party, has never been able to remove this nationalist “etiquette”. It is also seen by large part of Turkey’s population as an entity supporting terrorism. Internal struggles certainly play an important role in the party's failure to fully detach from the allegations of support to terrorism and become more of a “Turkey’s party”. I shall say that, since the Gezi events in 2013, more and more Turks have seen in the HDP a more “democratic rights for all” oriented movement, but this is certainly not enough.

Having already said my views about the IYI and MHP, it is therefore not wrong to say that today there is no political entity that can genuinely endorse a Europeanisation agenda. We shall hope for a democratic way out from the nationalist, anti-democratic environment and remind every one of Turkey’s long commitment to European/Western/Universal human rights and democratic values.

To Top

To Top