Photo justplay1412/Shutterstock

A picture of the transformations of funding to Italian politics, from the introduction of direct public funding to political parties in 1974 to its abolition and the regulation of transparency in recent years

Accounting for the transformations of the financing mechanisms of Italian politics is not a simple undertaking, especially considering the fact that the country is among those in Europe that have most frequently modified the relevant legislation. Only in the last fifteen years, Italy has adopted eight reform laws on the financing of political parties, while the provision of a single text bringing together and coordinating the existing rules has not been implemented yet.

Trying to simplify the matter and identify the norms that have most significantly impacted the ways in which political actors are financed in Italy and the amount of economic resources actually available to them, we will focus on two main moments of transition. The first is the introduction of direct public funding to parties with the law 195/1974 (and further reform provisions), that made the State the main source of livelihood of Italian political parties, first integrating and then replacing self-support and private financing. The legislation introduced in 1974 did not set binding requirements for parties nor it regulated their internal organisational arrangements. Furthermore, there was no reliable system of checks designed to safeguard the legality of party revenues and transparency measures were limited, to say the least. Overall, in this first phase, the political party was appropriately described as an "undisciplined prince", who benefited from privileges without having to give anything in return.

The outcome of the 1993 referendum, as is known, did not change the substance of things. Despite the abolition of direct financing for ordinary expenses, the provisions introduced from that year appeared in continuity with the previous phase, particularly as regards the increase in the amount of public financing and the system of checks, still very poor.

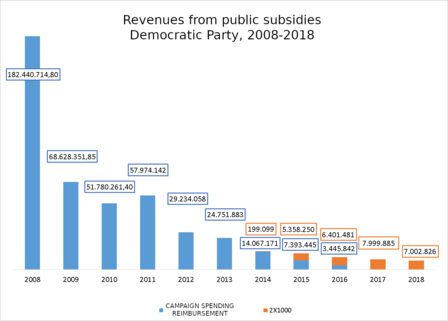

Starting from 2008, instead, the Italian legislator implemented a significant change of pace, with legislative corrections aimed at reducing the amount of reimbursements for electoral campaigns, which culminated with two radical reforms: the first, introduced by law 96/2012, halved the total amount of public grants for political parties, while the second, law 12/2014, eliminated all forms of direct public financing, leaving only forms of indirect public funding. The figure below shows, for example, the effects of the curtailment of public funding on the revenues of the Democratic Party over this last decade. Following the cut of the reimbursements for electoral expenses, which became effective starting from 2017, all is left are the proceeds from the voluntary destination of 2x1000 personal income tax, of considerably reduced scope compared to the previous years.

Alongside the loss of revenue from public funding, the two reform laws introduced the first provisions concerning the legal regulation of the party entities. Parties remain unrecognised private associations governed by the Civil Code, and therefore maintain a large part of their organisational autonomy, but have had to provide themselves with statutes drawn up by public deed in accordance with "democratic principles of internal life", the minimum contents of which are explicitly specified in the legislation. They must also submit their financial statements to the assessment of external auditors, publish accounting documents on their institutional website, and submit to the control of a new body responsible for annual reporting, the "Commission for guaranteeing the statutes and for the transparency and control of the financial statements of political parties".

Many see as paradoxical that the Italian legislator introduced a system of rules aimed at regulating the internal organisation of political parties (albeit in a way that remains not very penetrating) and that the latter have had to renounce the confidentiality of their financial management, reporting their financial statements to competent authorities and making their main incoming and outgoing cashflows accessible to the public just when public funding was cut. In fact, in the experience of other European countries, the interference with the organisational autonomy of political parties by the State has found justification in the introduction of public funding and certainly not in its abolition. The Italian context, on the other hand, has reversed the route in terms of the historically reticent positions on the introduction of a discipline of the internal order of political parties. The "prince", discredited and impoverished, now appears to have to navigate a considerably more regulated environment.

*University of Turin

This publication has been produced within the project ESVEI, supported in part by a grant from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the OSIFE of the Open Society Foundations. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa.

To Top

To Top