Jozip Broz Tito

How many streets and squares in the former Yugoslav states are still dedicated to Jozip Broz Tito? A comment

Names of streets and squares accompany the daily collective experience of citizens – as often ignored, forgotten, or reinterpreted in their original meanings as put at the centre of debates and disputes. The recent case of Zagreb's Tito Square is just one of many examples.

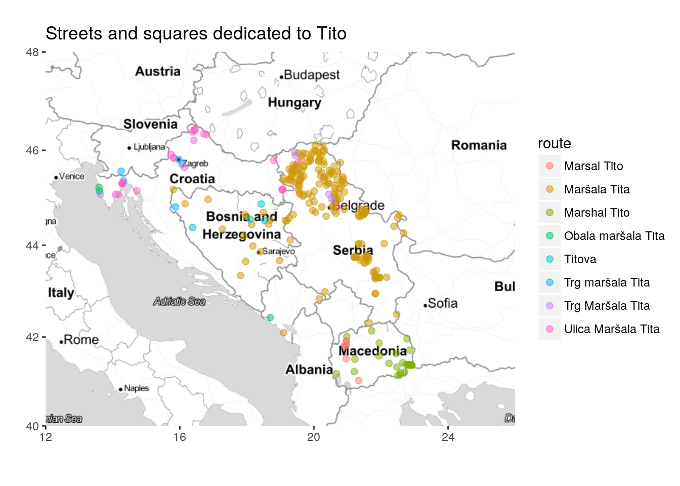

In the former Yugoslav countries, the focus is on the relationship with the recent past, and the figure of the leader who led the federation for 35 years is probably the most debated. Further confirmation came from the attention paid by South-East European media to the recent mapping of the streets still named after Tito , elaborated by Giorgio Comai, OBCT – a valuable effort that, thanks to large-scale data capture, provides an unprecedented picture and much food for thought.

Urban public space

Urban public space is a powerful channel for shaping politics and representation: renaming streets and squares is the quickest (and cheapest) method to this end. In the Yugoslav era, most towns featured at least one square or street dedicated to Marshal Tito. Some cities had even integrated Tito in their own name – see for instance Titograd, Titovo Užice, Titova Korenica, and Titov Veles. The end of socialism and the dissolution of the country have swept away such denominations, and the same has happened with the main arteries of the new national capitals: Marshal Tito street disappeared in Ljubljana and Belgrade, as did Marshal Tito square in Skopje. A street and a square survived, respectively, in war-torn Sarajevo and in the Zagreb of president Tudjman's national reconciliation.

However, the issue concerns hundreds of towns and cities. Traces of the socialist past were not erased overnight, and urban landscapes are still sites of confrontation and elaboration. In many cases, policy is conditioned or shaped by the needs of new national narratives; in others, the past is defended as an important reference for the present.

We are often accustomed to look at memory policy as something centralised, top-down, emanating from the political leadership of the state structure. Studying the maps of "Finding Tito" , on the other hand, enables us to look at local, regional, or city contexts. Managing toponymy is almost always up to local governments and communities, in a non-systematic process producing many different outcomes, all worth investigating.

Looking for Tito

Exploring the map, the attention is inevitably drawn to Vojvodina, as the autonomous region of Serbia is scattered with markers indicating the presence of streets named after the Marshal. In a territory where dozens of different national groups coexist, Tito's "brotherhood and unity" is still regarded as meaningful. Bigger cities like Novi Sad, Zrenjanin, Pančevo, Sremska Mitrovica, Sombor, and Kikinda have basically acted as in the rest of the country, erasing all references to the Yugoslav leader (with the exception of Subotica). Tito, however, remains remarkably present in small centres and in places where the revisionist process has been much slower due to lesser exposure to the "ethnifying" efforts of the official memory policy.

Another region that stands out for its peculiar concentration of Tito references is Istria (and Kvarner), where the Marshal is still featured in the names of streets, squares, and parks in coastal towns such as Koper, Pula, Umag, Novigrad, Rovinj, Poreč, and Rijeka. Here, reasons may be varied. First, Tito is regarded as the promoter of the reunification of the aforementioned territories with Croatia (within the Yugoslav federation) after the Second World War. In addition, even after the 1990s, the region has been characterised by a political orientation of regionalist or social-democratic nature, far from that of the revisionist Croatian right that most often promotes the removal of symbols of the socialist past.

If looking at Lika and Dalmatia, however, almost every trace of the Yugoslav leader is lost – the last big town to give up on its Marshal Tito street was Sebenico, in 2015. These are areas that were particularly affected by the conflict of the 1990s. At the time of the Krajina Serb Republic, separatist administrations committed to redefine the toponymy to enhance the "Serbian nature" of the territory, while a parallel operation was conducted in areas under Zagreb's control. In 1995, the Croatian recapture of Serb-controlled territories did not put back the clock. In this process of double erasure, the small centre of Donji Lapac holds on to its Marshal Tito street, standing out as the only exception in this part of the country.

Similar dynamics have emerged in Kosovo, where the tormented events of the last decade of the 20th century have erased the name of Tito from the maps. This is best illustrated by the case of Prishtina's old "Maršala Tita", a major pedestrian street in the city centre. Renamed Vidovdanska in the early 1990s (in memory of St. Vitus' Day and the Battle of Kosovo Polje – the Serbian national myth), it became Boulevard Mother Teresa after the 1999 conflict, in honour of the famous nun and missionary, born in Skopje by a family of Albanian-Kosovar origins.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the affirmation of Republika Srpska's national identity has long led to the disappearance of references to Tito within the boundaries of the entity governed by Banja Luka. Significant exceptions remain in war-torn Srebrenica and Kozarac, characterised by the significant presence of the Bosniak community and the attention of international observers. In the other entity, the Federation, the Marshal is still featured in the main "multiethnic" cities such as Sarajevo, Mostar, Tuzla, and Zenica (with the exception of Travnik), in the densely populated cantons of Tuzla and Zenica-Doboj, while he seems to have almost completely deserted the more rural areas.

The patchy distribution that characterises the Macedonian territory largely reflects the country's political context, marked by divergent attitudes on Tito's memory and the Yugoslav experience. It was during the socialist era that Macedonia had its borders, institutions, and national identity recognised for the first time. However, other narratives insist on the need for a complete break with that past. Divisions within society and among the main parties are reproduced locally, conditioning the toponymy.

Returns

What "Finding Tito" cannot tell us, however, is the historical depth of the phenomenon and the different phases of memory policy in the region. While, on the one hand, it shows very effectively the results of "decommemoration" – to quote Srđan Radović, a scholar who has worked on the topic for a long time –, it does not detect the opposite processes of "recommemoration" and "return" of Tito.

For example, the Ljubljana case once again demonstrates Slovenia's conflicted relationship with its Yugoslav past. Marshal Tito street, the city's main artery in Yugoslav times, was renamed as early as 1991. In 2009, however, the local administration dedicated to Tito a new, long street leading from the suburbs to the centre. The decision was very controversial, and just a couple of years later – following appeals by some citizens – the Slovenian Constitutional Court deemed the reference to the Marshal unconstitutional as a symbol of a totalitarian system, repressive of human rights and freedoms.

The long avenue Josip Broz Tito in Podgorica is also the result of recent developments. The city, renamed Titograd in 1946, did not have a street dedicated to Tito in the socialist era. The one we find in today's maps of the Montenegrin capital is the result of a re-commemoration process in the mid-2000s. In other cases, the revision of the toponymy recognised the historical importance of the character, replacing however the emphatic "Marshal Tito street" of Yugoslav times with a more restrained "Josip Broz Tito street". Tito's birth town, Kumrovec, even renounced the famous nickname, sticking with a simple "Josip Broz" – a touch that ended up fooling the Google Maps query.

These dynamics show how much the public debate on Tito and, more generally, the socialist period remains open across the region, albeit with different tones. The very naming of former Tito Square in Zagreb was repeatedly supported, contested, and approved over the years before the recent removal. The matter seems far from closed, as more than a few have promised to act to bring the Marshal's name back to what they think is its rightful place.

The author suggests:

A book: Srđan Radović, Grad kao tekst , Bibiloteka XX vek. Belgrade, 2013.

A documentary: Nestanak heroja / Disappearance of Heroes by Ivan Mandić

(Serbia, 2009)