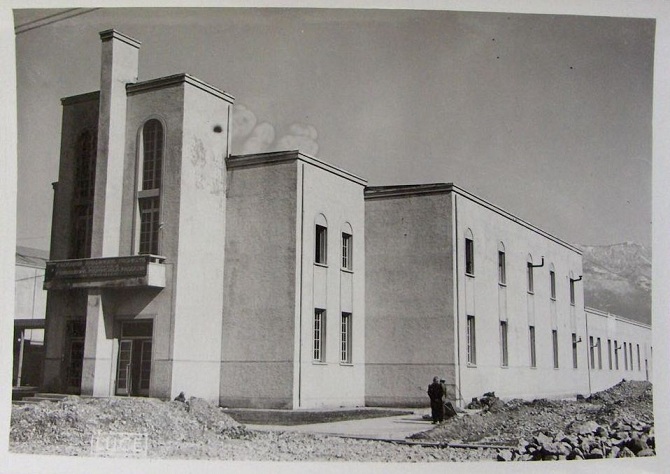

The National Theatre in Tirana (photo T. Mali)

According to the umpteenth architectural project of the Rama government, the building housing the National Theatre risks demolition. Once again, the history and memory of the country are in danger. A comment

Born in 1938 as an "Italian-Albanian club", the building that now houses the National Theatre was one of the first architectural interventions by Italians in Albania. The goal of the future occupiers – Italy invaded the country only in April 1939, after several years of economic and cultural penetration – was to monumentalise the centre of the capital, favouring fascist propaganda and more generally relations between the two countries.

Designed by architect Giulio Bertè a few steps away from what is still today Skanderbeg Square, the building was to be a large cultural and sports center, containing a cinema, swimming pool, and various dining areas. Since 1947 this structure has housed the main theatrical centre of Albania: the 430-seat hall of the National Theatre along with other smaller ones of the Experimental Theatre Kujtim Spahivogli, the last one inaugurated only last December. All this seems not to suffice for the Albanian authorities, who have announced the demolition.

Let's demolish!

According to a 2008 research by the Bari Polytechnical Institute , the building was made with prefabricated material in Milan – an experimental cement mixed with poplar fibers and algae, to be framed in a broader context of experiences between the two world wars. Known with the commercial name "populit", the building material was widely used until the 1970s. Today, the construction technique has ended up under accusation, leaving a halo of sudden danger around the building.

For the Albanian authorities, the building – which unfortunately over the years has undergone partial and inadequate maintenance – has suddenly become unaccessible, with the short construction time and the material used at the time making restoration futile. If the debate has raged for months, socialist premier Edi Rama intervened only a few days ago, to claim that he has followed the polemics "without particular attention" and state that the building "does not even have the standards of a municipal theatre" and that demolition is not negotiable. "The only regret is having lost so much time", he said. Socialist mayor Erion Veliaj agrees that not only the theatre has no monumental value, but the instability would endanger the staff and the audience. As if this were not enough, he added that the structure would contain traces of asbestos, and that over the years this has caused serious health problems to the actors.

While brandishing it like a hammer, neither politician mentioned that the research – which is, by the way, not a technical study, but an historical effort carried out in the context of a graduation lab – stresses the remarkable historical-documentary value of the building, due to experimental research on these materials carried out during the autarchic period, but also to the architectural character and the urban role of great interest: a sort of "island", estranged from its context, which even resisted the speculation of the 1990s. In short, the very study that describes the incriminated materials actually calls for the recovery of a fragment of historical memory and the reinterpretation of its urban function.

After all, as already mentioned by Albanian scholar Romeo Kodra , an example of Italian industrial architecture and early twentieth century Italian rationalism just cannot be razed to the ground without specific studies. Demolishing because of asbestos – instead of cleaning up – is equally absurd.

New project, old acquaintances, no competition

Moreover, as is often the case, "security" is the excuse thrown to the people, but the real reasons that make the demolition of such a valuable object so much "necessary" reside elsewhere. The project presented by the Albanian government for the intervention on the entire area of the National Theatre is signed by the Bjarke Ingels Group, an avant-garde architecture firm in Tirana, already known for winning a competition in 2011 for the construction of a large cultural centre. The project was then set aside due to the interruption of the Rama administration after the administrative elections of the same year. Since then, in the country "redesigned" by the marker of the premier-artist, some instruments of regularity and transparency – certainly often and willingly purely formal in Albania, but in place anyway – have been systematically avoided, such as public tenders and competitions, and this time the Danish starchitect came to Tirana on a "direct call".

In fact, only some eye-catching renderings were made of the new headquarters of the National Theatre: most of the elements are not yet known to the public. We already know that the new theatre will have a 620-seat main hall and three smaller rooms. From one of the slides, however, it is clear that three new buildings will join the new theatre, overlooking one of the few pedestrian streets of the city, already suffocated by impressive hotels and shopping centres. "Of course, the company will not come to build the theatre to go bankrupt", was the premier's only comment.

The 3 Ps of the socialist government

Also for the project of the National Theatre, the Albanian government has activated the formula of public-private partnership – an instrument that aims to finance large public constructions with private investments, yielding land or other public resources to contracting companies.

In March, the International Monetary Fund asked the Albanian government to suspend the construction of works through this formula, since the institutional framework for it is considered too improvised and fragmentary. According to the IMF – which, we remind, is not exactly a den of artists obsessed by historical memory – "all the concessions, including those related to the big projects recently approved, are the result of a process that is not really formal" and would require therefore a more careful analysis of costs and profits as well as greater attention to public debt.

This lack of transparency on concession contracts and the absence of an investment strategy has fuelled many criticisms even within Albania. If one lives in Tirana, he has the feeling that, since when the government and the municipal administration are both controlled by the socialists, the cement has been pouring more than ever. According to data from the Albanian Institute of Statistics (INSTAT), with the Rama-Veliaj tandem, only in 2017 231 building permits were issued in Tirana, with an increase of 118% compared to the previous year – all in spite of the electoral promises of moratorium and "zero new buildings" by the mayor of Tirana.

The transformation of the capital and the capitulation of institutions

The demolition of the National Theatre would not be the first intervention that upsets the urban layout of the "Italian Tirana". In 2016, again to guarantee "dignity" and "better working conditions" – for the Football Federation and the Albanian national team – the Rama government decided to bring down the stadium "Qemal Stafa", i.e. the final part of what used to be the monumental "Avenue of the Empire", the boulevard that even today crosses the city centre. Demolished in spite of numerous opposing voices, a new stadium is under construction in its place, but also a building with 24 floors in addition to the 7 of the stadium – a space clearly used for commercial purposes by the private company that will finance most of the works, always in the name of the 3 Ps.

It is significant that a government that has been riding the waves of legality since gaining power, with the slogan "we make the state", imposing compliance with the rules and laws notoriously evaded by both citizens and institutions, is so casual in the cancellation of theatres and stadiums from the list of monuments protected as cultural assets , evidently for the sole purpose of paving the way for their demolition. Such a dance of revocation of protections and issuing building permits reveals how laws and regulations respond first of all to political and economic interests, and raises serious doubts about the way in which the architectural heritage and the common goods of the country are managed, today more than ever at the mercy of the interests of a few.

Need for clarity

The overlapping of feelings and viewpoints around a particularly complex and sensitive case inevitably generates a lot of confusion. Some demand dignified spaces for the National Theatre and propose risky alternative projects, some call for preserving the heritage and memory of the place and stopping speculation, some protest against the appropriation of public spaces in the historic centre of the capital. In this context we should question the arguments presented to justify the demolition of the building at all costs, we should question the a priori positions favourable to any conservation, we should question the formula through which works will be financed, and reject the arbitrariness with which the project has been conceived and imposed on the citizenship as much as the emotions linked to the memory of a place that is lost if it is not transformed.

We need communication and transparency or, in other words, a responsible and European debate and ruling class.

To Top

To Top