Precious wood logs in front of a sawmill - Photo by Marta Abbà

Despite the 2016 moratorium, illegal logging continues in Albania, fueled by corruption, weak law enforcement, and European demand, particularly from Italy. However, new EU regulations designed to combat this issue risk pushing small businesses toward timber mafias

Massacre. Those who have seen it with their own eyes and dare to speak describe it as a “massacre,” but most remain silent, nodding, communicating with glances, or lowering their eyes. “We saw them load a unique species of ancient beech, top-quality wood, onto their trucks. No rules were followed; they cut down whatever they wanted,” says Ahmeti Mehmeti, a forestry engineer who has worked for years as a freelance anti-deforestation consultant.

Andi Bego, a local specialist with the environmental NGO PPNEA , completes the description of the supply chain: “After illegally logging, they set fire to the area to erase all traces. The forests in this area (Bishnica, west of Pogradec) are also used for firewood, but most of it is exported to neighbouring countries.” He mentions Italy and Greece, though he has no proof beyond vivid images etched in his memory: “After 2005, massive illegal logging began, and it continues today, growing and undisturbed.”

In this remote area, one of the few where something still remains, there are no records. The available national data support Bego’s claims, as do satellite images, but the trail of the sacrificed logs goes cold.

The central government and the European Union legislate from afar, from above, and their bans ineffectively gloss over local dynamics, revealing their unaware fragility in the face of the persistent demand for wood directed at this country.

A porous moratorium

According to INSTAT , between 2018 and 2023, Albania lost 320,000 hectares of forest and pastureland (18%), including 82,000 hectares of “pure” forest (7%). In 2023, Global Forest Watch reported a loss of 2,200 hectares, equivalent to 1.01 Mt of CO₂ emissions, marking the “final sprint” of a “massacre” ongoing for over 25 years, largely ignored and facilitated by poor local traceability.

In 2014, the issue gained brief attention thanks to the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network , which reported “1.3 million cubic meters of trees illegally felled in 2011.” But that was an investigation about Romania; the Albanian data was incidental, much like the areas where Albanian forests continue to be illegally destroyed today. Everyone living there (and willing to comment) confirms this, painting a picture of local corruption supported by close collaboration with officials tasked with protecting the land, yet there is neither proof nor arrests.

In the official silence, the shrinking percentage of tree-covered land plays a solo tune, despite a 2016 moratorium (Law 5/2016 ) banning exploitation and prohibiting the trade and export of wood products until 2026.

Fines of up to 36,000 euros are imposed, except in three cases: cutting to meet local communities’ firewood needs, forest renewal and cleaning, or changes in land use.

Once the law was passed, government investment in the forestry sector plummeted: zero in both 2016 and 2017, according to INSTAT , and 220,000 euros in 2018 for “forest restoration.” Were those funds used to build roads to reach more remote forests?

Initially, the law seemed to yield positive results, but its limits became apparent over time. Reading the text closely reveals how predictable this was and why. There are no specific custom codes for the products banned from export, no limits on the amount of timber that can be taken “to meet residents’ firewood needs,” and no guidelines on per-person allocation.

Moreover, Albania lacks a national timber tracking system or a unified database to trace wood from harvest to sale. The devil hides in the details, generally, but in their absence, why bother hiding?

From the “outside,” few NGOs focus on this small country, which doesn’t impact any major player’s GDP. From the “inside,” few local organizations manage to both gain international attention and engage rural communities. All the more reason, then, why hide?

Alongside the moratorium, the government also made an institutional adjustment, transferring forest management responsibilities from central authorities to 61 municipalities, 33 of which, as of 2023, had no management plans, personnel, or monitoring equipment to implement them.

“Without a strong national framework to support them, this decentralization has clearly worsened the problem rather than solved it,” notes the Tirana Times in a recent article, explaining how the moratorium merely “pushed illegal logging into more remote areas.

Loggers have refined their methods to avoid detection (…) Instead of restoring order, it has cast the issue further into the shadows, making enforcement even harder. A blanket ban without institutional reforms, alternative economic incentives, and stronger enforcement mechanisms won’t address the root causes of illegal deforestation.”

They’re all called “Balkan forests,” but, as often happens with people, a tree’s fate depends on where it grows, with the difference that trees can’t move—except at the cost of their lives.

Albania faces a unique situation because “it’s the only country in the region with a moratorium and a significant portion of its forests (especially the most valuable ones) publicly owned, traditionally managed through management plans,” explains Davide Pettenella, professor of forest economics at the University of Padova , previously a FAO consultant in the Balkans. “This combination fosters the spread of corruption cases.”

EUTR, Europe’s veil over Albanian deforestation

Those hoping that the nearby European Union’s commitment to fighting deforestation would lead to improvement, if not a turning point, were mistaken. Neither the current EUTR (European Timber Regulation), in force since 2013, nor its evolved version, the EUDR (Regulation on Deforestation-free Products), which requires geolocation for every log imported into the EU, seem to have dented the effectiveness of the national deforestation mechanism.

Pettenella confirms this, explaining that even the latter “won’t impact corruption because it only addresses the legal origin of timber felled in forests, while the phenomenon involves the entire timber value chain, from forest to the sale of processed products. A significant portion of corruption occurs downstream of logging when timber is checked at checkpoints, measured, sold, exported… It’s clear that if timber from corrupt practices costs less than the proper market price, there’s an incentive to cut more, putting greater ‘pressure’ on forest owners.”

“Looking at official statistics, timber production data don’t match actual consumption,” the Tirana Times further notes, highlighting the scale of an underground economy that provides “short-term financial relief in Albania’s most remote areas.” These are national dynamics, but they are fueled by and feed off the international market.

It’s this market’s “pressure” that Pettenella refers to and that, according to several experts, could explain phenomena like document triangulation. Nothing new in the import-export world, despite the moratorium and EUTR, also because “in practice, the export of wood-based products previously imported into Albania isn’t banned, justifying potential commercial flows to Italy or other foreign countries,” explains Angelo Mariano, an expert in due diligence, EUTR, and EUDR at Conlegno .

It’s no coincidence that Mariano mentions Italy, as this country has long stood out as Albania’s top timber importer. The trade volume in the wood sector between the two economies is negligible for Italy (according to Assolegno , Albania is the 34th supplier for Italy’s wood macrosystem, which, in the first four months of 2024, imported 1,579.02 million euros from the EU and 345.86 million euros from outside Europe), but for Albania, Italy’s hunger for wood is vital.

According to the World Bank , in 2022, Albania’s exports were driven by Italian demand, accounting for 61% of the share, followed by Greece (15%).

These figures capture the legal and overall trade in the sector. Neither the moratorium nor the EUTR prohibits Albania from exporting products made with foreign wood, and the country’s relatively low labour costs would justify this dynamic.

To better understand what happens to the precious beech, which locals claim continues to lose ancient and valuable specimens, the UN Comtrade database shows flows of raw wood (Hs 440392) exported until 2015, including to Italy, followed by only sawn and cut wood (Hs 440792), which still reaches Italy without any post-moratorium or post-EUTR decline.

Timber flows but paper-based controls

Despite the halt in the legal outflow of raw wood, the continued export of lightly processed beech raises suspicions of ongoing triangulation, and Pettenella and Mariano’s words fuel these, confirming the ineffectiveness of EUTR (and EUDR) controls on this hypothetical black market between Albania and Italy.

The focus of regulators and law enforcement is almost solely on due diligence documents. In Italy, the Carabinieri Forestali check these at operators importing wood and wood products to verify their legal origin.

If everything is in order and they’re registered with the National EUTR Operators Registry , there are no fines and only an extremely slim chance of direct checks on “foreign” wood. The EUTR implementing decree, approved by MIPAAF on 19/9/2014, mandates checks only on a sample basis and two years after the product enters the EU (unless explicitly requested for strong reasons). Time passes, and suspicions linger.

Scanning the list of Italian companies in the sector doing business with Albania, one based in Zogno (Bergamo) stands out: Minelli Group .

Founded in 1937 as a firewood company, this family-run business now focuses on high-quality wood products, such as handles for brushes, knives, and brooms, stocks for sporting and recreational rifles, dowels for furniture, and components for wooden toys.

In 2014, at a Confindustria Bergamo conference, then-chairman Adriano Minelli spoke of a joint venture with Alhxef , a company based 20 kilometres from Tirana. The Corriere della Sera Bergamo reported it in local news, quoting him: “In Albania, we source beech wood directly, which, for low-cost products, is processed on-site.”

This was pre-moratorium, all legal, but post-moratorium, in 2024, BergamoNews confirmed the business in Albania, alongside recent export trends, much of it directed to the USA, where there’s also a branch in North Carolina.

Also post-moratorium, but back in 2017, Import Genius commercial data show five shipments from Alxhef to Minelli USA, mostly pallets and raw beech wood, via Gioia Tauro. If Albania can no longer be a “beech source,” what is it for Minelli Group?

When asked, the company explained that the choice was made “due to significantly lower labour costs, to remain competitive in certain markets,” and Alxhef has always been a mere “supplier of raw and semi-finished beech components, processed in Italy into products sold in Europe and the USA.”

On the moratorium, company representative Marcello Minelli denies that Albania was ever a beech source: “Alxhef was importing logs from abroad before 2016; we know they purchase from Montenegro and Kosovo, recently also from Greece.”

The misalignment of statements suggests tracing the supply chain backwards to Alxhef. Founded in 2001, according to Albanian public business registries, this company faced five seizures or administrative blocks between 2015 and 2022 and has always been authorized to provide “consulting and/or professional services related to forests and/or pastures” in Albanian territory. And it seems to still be doing so.

The silent pain of remote areas

In 2023, it began doing so for the Tropoja municipality, which didn’t sit well with the residents of the tiny village of Vrane e Madhe (within the Nikaj-Mürtur regional park). As soon as they saw loggers at work in their precious beech forest, they accused Alxhef and their municipality of illegal deforestation.

The only outlet to report on it, leaving a trace of the episode, was Citizens.al , documenting mutual accusations. Official documents show that Alxhef, as the sole bidder, won a tender in November 2022 worth 4,560,000 leke (about 46,000 euros) for six months for “firewood purchase,” and the following year, it repeated with a slightly lower value (4,370,000 leke, about 44,000 euros).

The treasury records transactions in its favour with matching dates for “heating services” from the Tropoja municipality and mentions transactions from other municipalities across the territory, including Elbasan, Kukës, and Pogradec.

The activities found in national databases are legal and legally declared—someone deemed them lawful—but the heated protest from the small village’s residents recalls the cracks in the moratorium highlighted by Tirana Times regarding the total absence of guidelines on per-person allocation or any limit on what qualifies as proper “firewood” use. There’s room for interpretation—and abuse.

When directly asked about Alxhef’s activities, CEO Xhafer Fiora states, “We don’t stockpile firewood; we have no contacts or contracts with companies in the sector. We’ve always imported material from Montenegro, Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, Greece—90% beech.”

And in Tropoja? Fiora confirms “complying with the contract, cutting only fallen, dry, or listed trees agreed upon with the Tropoja municipality,” specifying these are “closed contracts.”

However, on March 21, 2025, the Tropoja municipality confirmed via email that “A L Xh E F Shpk” is still operating in the area, denies issuing licenses for firewood cutting, and confirms holding public tenders for 8,489 cubic meters of wood total from 2020 to 2024. “Never had complaints from the Tropoja municipality or the Ministry of Environment,” Fiora emphasizes, overlooking those from the village residents reported by Citizens.al .

Once reached on-site, five hours by car from Tirana, exiting and re-entering Albania via Kosovo to shorten the route, none of the story’s protagonists could be found.

The angriest one has now turned to politics: elections are near, and he doesn’t want to revisit the episode. Near the area that became the stage for cross-accusations in 2023, we encounter a van with a group of youths warning against proceeding among the beech logs “because there’s a bear that’ll eat you,” and Pjetër Imeraj, Lekbibaj (Tropoja) administrator, who remains vague on the issue. Cutting, yes… massacre, no… local needs… Tropoja’s decisions.

Heading back toward the paved road, we meet two women who confirm the massacre. They’ve lived there forever and suggest the best route to leave—not because of bears: it’s getting dark.

What happened and is happening in the forests managed by the Tropoja municipality is revealed by satellites. They can’t assign blame but can show massacred areas and new roads for heavy vehicles appearing in the last five years—well after the moratorium took effect.

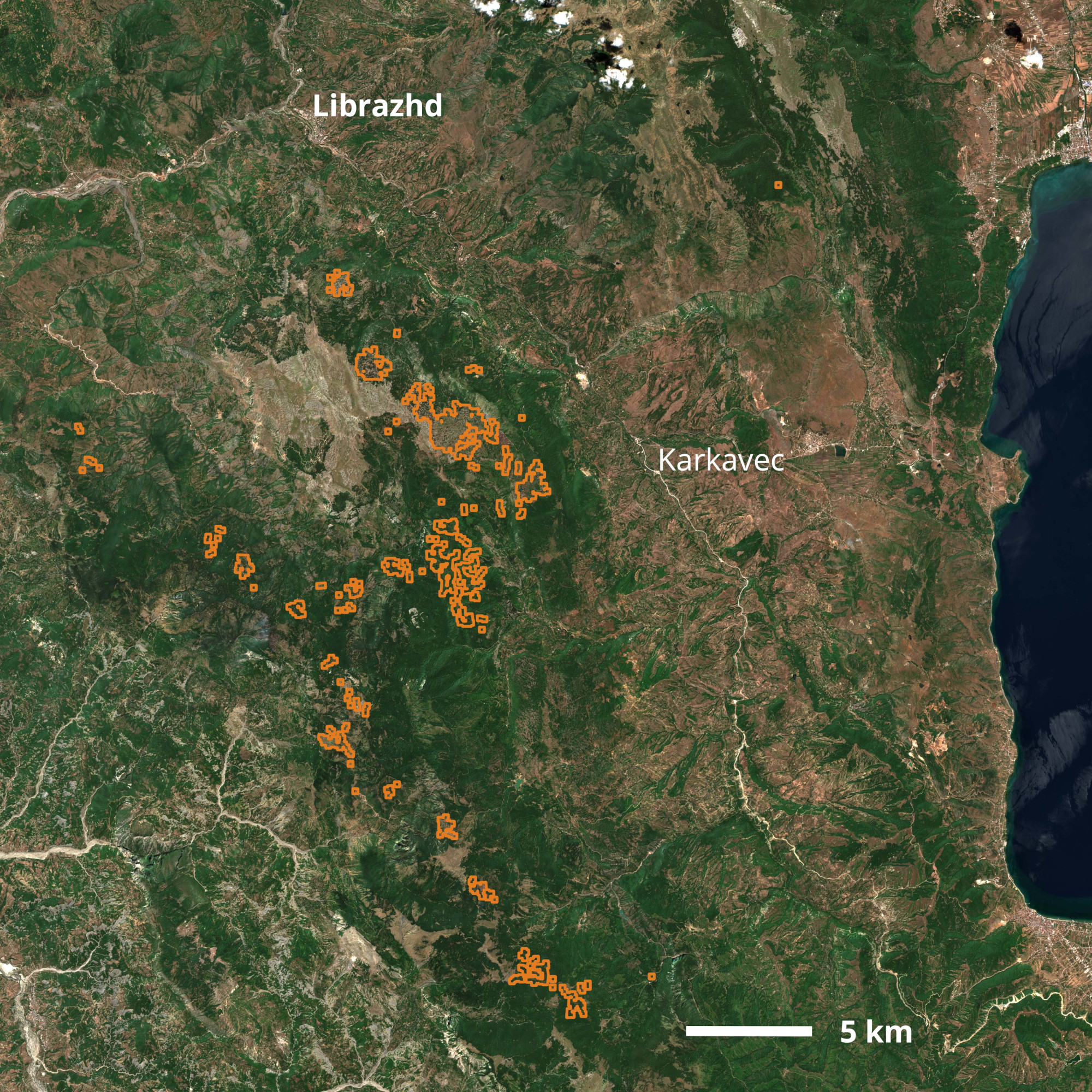

Flying over the country via satellite, it’s immediately clear that, in terms of massacre, the hardest-hit areas are around Pogradec. Here, total tree cover loss from 2017 to 2023 appears to be around 2,485 hectares.

Fewer hours from Tirana but more hectares of forest seem to have vanished during the moratorium. These are vast areas, hard to imagine sacrificed solely for local firewood consumption, but proving otherwise is difficult without a clear official quantity limit.

Estimated areas with high deforestation in the area between Librazhd and Pogradec after 2016

The satellite’s eyes and the words of Shpëtim Lato, administrator of the small village of Velçanit, 40 km south of Librazhd, remain. Reached via a 4x4 driven by a local, Lato, in his bar-meeting room-civic centre next to the school, recounts:

“Illegal logging continued until two months ago. I reported this phenomenon and met with people at the Pogradec municipality, but they told me they couldn’t do anything because the illegal loggers have strong political connections,” he says. “But I must admit, since then, we haven’t heard the sound of electric chainsaws. I truly hope this ‘silence’ lasts.”

What lingers, for far too long, is the silence enveloping Albanian territory when one tries to discuss illegal deforestation. A silence that echoes internationally and challenges Europe and its legislation against this phenomenon.

The dynamics uncovered by visiting and scouring the country’s databases, the incomplete puzzle pieced together by investigating the business case between Albania and Italy—between Minelli Group and Alxhef—don’t definitively prove any responsibility on their part, but they reveal many unanswered gaps and the difficulty of obtaining clear, complete answers.

Still, the hope is that this isn’t just an exercise in style, neither for the writer nor the reader, but a thorn in the side of those who govern and those who elect them. So that anti-deforestation laws stop being too-short, superficial blankets under which everything continues as usual, shifting to territories where reporting violations isn’t easy or convenient.

It continues, but a bit more in the dark, and this investigation aims to crack open a window and calls for keeping the light on.

This reportage was produced with the support of Journalismfund Europe

In collaboration with Elona Elezi , data reporting by Edward Boyda.

To Top

To Top