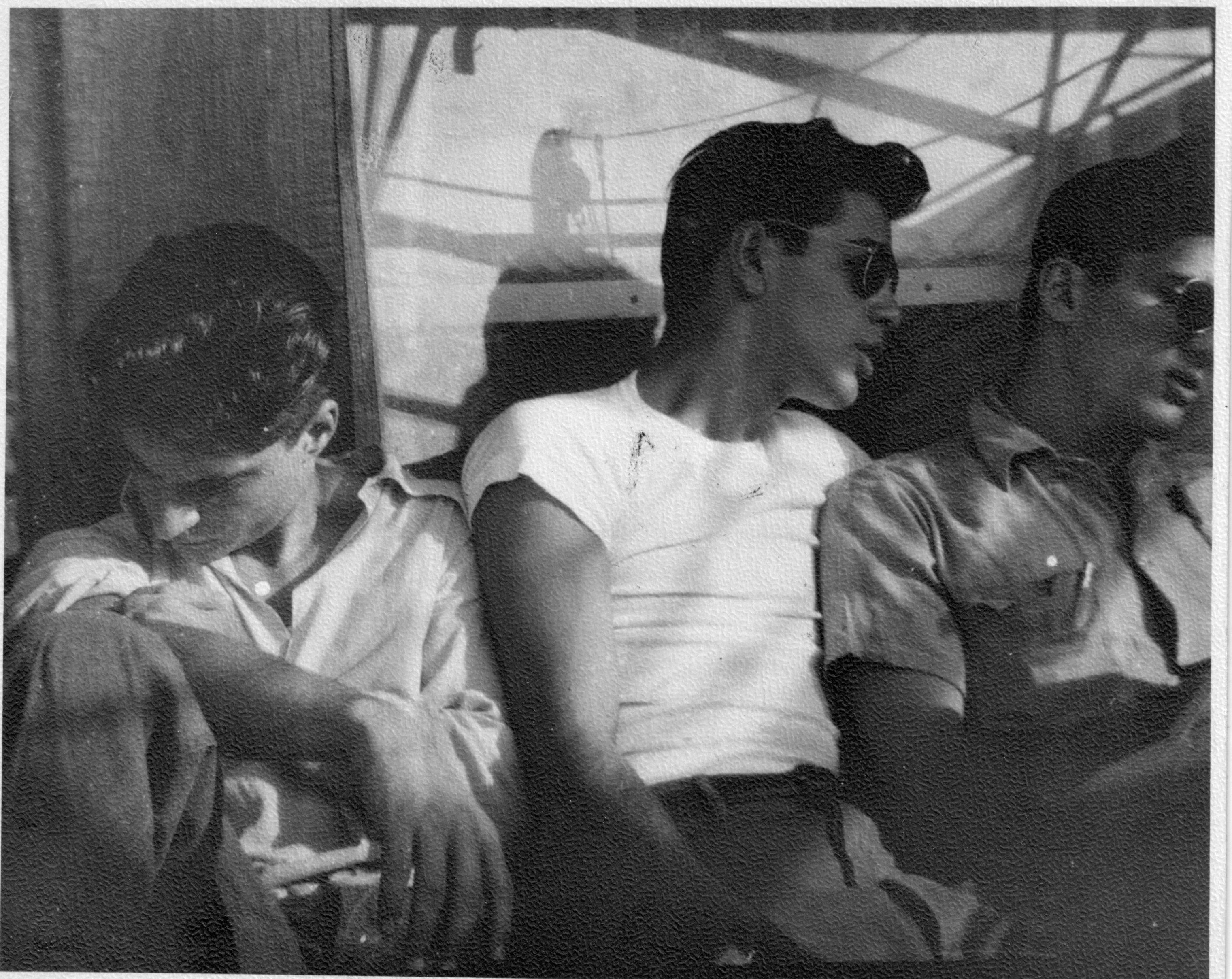

Armenian-American Repatriates Bobby (left), Paul (center), and Johnny (right) sailing on the Rossiya from New York to Armenia in 1947 - Photograph courtesy of Hazel Antaramian Hofman

As a young child, she always wondered why she lived in Yerevan when her father was born in the U.S. and her mother was from Lyon. Then she understood. With an historical-artistic project, Hazel Antaramian Hofman follows the footprints of those people, who, from all over the world, decided to migrate to Armenia after the Second World War

I was born in 1960, in Yerevan, Armenia, yet spoke little Armenian, and what I did speak was Western Armenian. As a young child, I always wondered why I came from such an exotic place when my father was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and my mother was from Lyon, France. Only after years of hearing stories did I realize that I was the product of two Armenian Diaspora post-World War II repatriate children, who were compelled by their father and mother’s emotive sense of hayrenik to leave one known cultural and ideological ground for another.

The post-WWII repatriation movements uprooted many Armenians from all over the world: France, Lebanon, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Syria, Bulgaria, Romania, Palestine, the United States, even some from Sudan, Iran, Iraq, India, Uruguay, Argentina, and China. It was an orchestrated campaign to repopulate what fraction that remained of a vast land well-documented as the ancestral home of Armenians from the time of Darius the Great. The repatriates were headed not to the romanticized, vast ancient land of their forebears, but to a “sovietized” Armenia under Stalin. It was a migratory event complete with personal and spiritual dispossession, and cultural disparity.

After World War II, Soviet-Turkish relations were stressed. Demands were made by the Soviets for the return of the Armenian provinces of Kars, Ardahan, Erzerum, Trebizond, Van and Bitlis from Turkey to Soviet Armenia. These were lands that were historically Armenian and, from 1878 to 1918, were under Russian rule. For two years, from 1918 to 1920, Armenia enjoyed a modern independence. The idea of returning these disputed territories to Soviet Armenia was important to all Armenians, including those living in the Diaspora. The Soviet claim to these lands was a political push that acted in concert with the aspirations of the Armenian Diaspora. The repatriation movement was another facet of the Armenian people’s historical memory of Genocide, abandonment, and forced emigration from the Ottoman Empire during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Ultimately, shifts in alliances after the Second World War between the Soviets and the West, notably the United States, and the West and Kemalist Turkey sealed the fate of these lands.

Many Armenians in the Diaspora maintained a strong connection to their Christian faith and devotion to their heritage, establishing Armenian churches and schools in their host countries. Given the propensity for religious devotion by the Armenians abroad, Kremlin domestic policy began stressing the concept of homeland after 1941. Communist ideology was downplayed in favor of Armenian patriotism and the Church. The Soviet maneuver to secure the backing of the Armenian Church was a critical aspect of its propaganda process. Armenian clergy became involved in the plea to Armenians worldwide to return to the “fatherland.” The new Catholicos, Georg (Kevork) VI, who was elected in 1945 by the Ecclesiastical Conclave in Soviet Armenia made his worldwide appeal to Armenians to return “home.” In reality, any support that was given to the Armenian Church by the Soviet state was politically motivated. It did not negate years of Soviet erosion of the church nor the continued persecution of that institution. Soviet culture changed much in the way of Armenian tradition including the union of the Armenian people and their religious faith, the major social institution that has held the Armenians together as a people for millennia.

The Republic of Armenia was in a state of extreme poverty after World War II. By November of 1945, Stalin authorized the return of Armenians to Soviet Armenia with the incentive of bringing in new life in the construction, vitalization, and economic development to a destitute Soviet Republic. Armenian nationalistic organizations, political parties, and religious leadership organized efforts of the repatriation. The Armenian Repatriation Committee stressed the need to nationally support the country of Armenia while downplaying the reality that Armenia was now a Soviet-dominated country.

The basic repatriation story is riddled with individual twists and turns, but in most cases, there was a common thread: more often, a nationalistic, or at times, a socialist-leaning decision was made by a patriarch or a matriarch, who uprooted their family in response to an emotional global appeal encouraged by Soviet propaganda. The call to Armenians worldwide was a maneuver to attract young people of child-bearing ages; to secure skilled workers and professionals from developed countries; and to obtain new technologies and products. Encouraged by promises of free housing, land to build upon, and job opportunities, those who left the Diaspora made their life-altering move with false hope. Upon their arrival, they witnessed unimaginable social and economic conditions, with no opportunity to leave the Soviet bloc Armenia or regain their confiscated citizenship papers. The collective social memory of many hayrenadartsner was one of betrayal and deceit under the guise of a patriotic call. Those who survived the times would later tell stories concerning backward social economics, disease, discrimination, psychological anxiety, and physical brutality encountered under the Soviet system. Zabel (Chookaszian) Melconian, a twenty-three year old New York native left the United States in 1947, to support her father’s decision to move to Armenia. After experiencing abysmal living conditions, she recalls trying to warn her relatives in America not to come to Armenia by sending them cryptic messages in outbound letters, which were routinely censored.

Scholarly articles, lectures, and testimonial documentation have only begun to shed light on this period in Armenian history. Crosby Phillian, a native New Yorker, who left the United States in 1949, at the age of sixteen, says that “survival” was the sole mantra of many repatriates who when living in Armenia had to sell their personal belongings on the black market for a few rubles in order to eat for the week. The sale of goods on the black market became a ritual every Sunday. Anxiety-ridden akhbars were at the mercy of those who had some money and knew how to work the system. Phillian, who currently lives in France, also notes that the unwritten law in the Soviet Union at the time seemed to be standing in long lines to buy basic food items, such as bread, meat, or cheese. Bursting crowds, arguments, and physical fights were not unusual occurrences in these lines. There was even an occasional death. Phillian remembers when a man, who was trying to simply buy some cheese, was killed by a woman’s shoe heel striking his head.

My own personal memory of life as a child in Armenia is limited and untainted by the social conditions experienced by my elders. Later in my life, when I listened to family stories, I knew that there was a painful difference in the cultural experiences of my parents between the times they grew up as youth outside of Armenia and later as they matured during their formative years in Armenia.

Upon reflection, I can only imagine the culture shock witnessed by those who grew up in the late 1940s in the United States, where the sounds of Count Basie, Benny Goodman, and Frank Sinatra were popular, and the faces of Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart, Lana Turner, and Loretta Young dominated the silver screen. There were those however whose experiences were not all that bleak. At some point they knew how to work within the Soviet system. They found government work or had a lucrative trade or profession that allowed them to cultivate a reasonably profitable place for themselves. Others knew how to work the system by bribing officials. But there were those who suffered greatly. They fell into states of poor health, and extreme stress and poverty. The bleakest experiences however were those who were exiled from Armenia to Siberia or Central Asia, never to return. Given the disparity of life before and after the post-WWII repatriation, how does one capture the innocent memories of those children born in Armenia to repatriates? These were the young children, born to akhbars. Ignorant of the plight of their family’s situation, these children grew up among the children of the dekhatseez, the generational Armenians from the area. Never really fitting into native Armenian life, many children of akhbars later experienced their own social discrimination, life-threatening illnesses, and degrees of poverty.

The feature

A century ago, the Armenian genocide marked the end of the Turkish-Armenian cohabitation in Anatolia and entrusted the Arabian Levant with the destiny of the survivors. Aleppo, Damascus, Baghdad and Amman thus became the bosom of the Armenian diaspora.

It is in Lebanon, though, where the highest peak of understanding is reached between the Armenian exile and the Arab world. The Diaspora University is founded in Beirut, Armenian awareness and political claims rise, the myth of the return survives and is renewed, the soul of the largest Armenian community in the Middle-East expresses itself. It is from Beirut that the diaspora spread to Europe, United States, South America and Africa.

Paolo Martino departed from Beirut and, through Eastern Turkey, Jordan and Syria, he reached Yerevan, the capital of Mother Armenia, so evoked yet such a stranger. The report From the Caucasus to Beirut runs over the umbilical cord of the diaspora through places of escape and exile. In the background, an Arab Spring-stricken Middle-East, the most powerful wind of change that has ever blown over those skies.

My questions continue to abound: how does one reconcile the profound loss of cultural freedoms and mistrust of repatriate American-Armenians amidst the Cold War, or how did Christian Armenian repatriates handle the religious suppression in a Soviet Armenia? To understand and to retell the story, I turned to ethnographic research and to my art. In 2010, I began personal interviews and the collection of family photographs, memoirs, and travel papers. Based on these sources along with historical documentation, my interest was to capture this multi-faceted story through paintings, drawings, and installation art, as an expression and interpretation of social experiences. When author and family friend Tom Mooradian visited Fresno in the Fall of 2009 (and then later in 2011), during the promotion tours of his memoir, Repatriate: Love, Basketball, and the KGB, I found that we shared each other’s understanding that there were more personal histories that needed to be documented. But as I indicated to Tom, my goal was not to write people’s individual biographies, but to use imagery and text to narrate the story of the late 1940s repatriation within the manifold of twentieth-century Armenian history. Not only would I better understand my own early personal story, but I would be able to collect oral history to artistically interpret the culture shock, loss of freedom, and the ideological turmoil that shaped the historical time of the akhbars.

In December 2011, I traveled to Paris, France, to make contact with old family friends who had repatriated in 1947 and left Armenia in 1966. Stories about the post-war departures from France to Armenia were convoluted, depressing, and at times surreal. Over six decades have passed since a bizarre stand-off at the Marseilles port just days before the Russian repatriation ship set sail on December 24, 1947. Stranded aboard the Pobeda, three hundred French-Armenians awaited their travel plans. They were denied permission by French authorities to sail from Marseilles and subsequently told to disembark. The ship eventually set sail with 1,122 Armenians, without the 300 French-Armenians who the French considered part of their citizenry. Twelve-years old at the time, Virginia (Hekimian) Antaramian, who was born in France to foreign born parents, recalls several sketchy events of that day. She remembers being surreptitiously guided to the ship by her communist Uncle Hagop Chiljian like many other French-born children of French-Armenians, then waiting in hiding onboard expecting to be joined later by her parents. For the French, who lost many citizens in the war, it was a matter of safeguarding their young populace. Virginia heard about other children who were placed in a similar situation. They were covertly taken to the main ship in small boats in the middle of the night to get on board without knowledge of the French authorities, or were carted in large crate boxes to the Pobeda. Ultimately, those who were not originally given permission to sail from Marseilles were allowed to leave France.

As stories go, there was also the romantic encased within the surreal. It was the determination of Hagop Dertlian, a staunch Armenian communist to take his wife and four of his five daughters to Armenia. Living on the outskirts of Paris, twenty-year old Esther, the second eldest of the five girls, became emotionally torn when she had to leave her beloved city of Paris so that she could emotionally support her mother and younger sisters, who all reluctantly traveled to Armenia in 1947. Around this time Esther’s oldest sister, Armenouhi, had moved to the United States when she married an American soldier after the war. Their third sister, Alice, who at the time of the departure to Armenia was not prepared to leave Paris, stayed in the city for a short before leaving for the United States to join Armenouhi. It was in Armenia however where Esther met and married the love of her life, Dickran Sahaguian, a French-Armenian. The irony is that these two had lived for many years in the same small Parisian suburb prior to the repatriation, but had never met until their lives entwined in Armenia after 1947.

Other stories strike a more somber chord. The mother of Virginie, Dirouhee (Samuelian) Hekimian, an educated socialist who after convincing the family to repatriate from Décines, outside of Lyon, France, to Armenia in 1947, suddenly found herself confronted by the grave illnesses of her husband and two children three years later. To survive she sold all of the family’s valuable possessions on the Soviet black market for a petty amount of rubles. The family lived in poverty for many years. Their living conditions amounted to a cesspool for contracting diseases. Her daughter, Virginie, was diagnosed with typhoid, while her son, Massis, only five-years old at the time, developed severe dysentery as her ailing husband was lying in the hospital. Virginie recalls how much her religious mother suffered and how she prayed fervently every night for miracles.

In March of 2012, I took my second journey to collect stories and photographs for my project. I went to Yerevan to visit an old family acquaintance and her family. She was not part of the repatriation, but during her younger years she had befriended many Armenians who came from America and France. As we gathered for our evening meals, neighbors or workplace friends, people who either remembered stories of repatriates or were themselves children of repatriates but never had an opportunity to leave the country, came to tell stories. The most interesting stories shared were those of the unrecognized contributions in technology and specialty trades that Armenians from the Diaspora made to Armenian society. All in all, the cosmopolitanism of Yerevan was born from those Armenians who came from the outside.

All advanced technology from America was valuable and sought after by Armenian repatriate organizers and the Soviets as part of their effort to rebuild and advance the underdeveloped country of Armenia. So much so was this objective that the Soviet government funded extravagant travel for many repatriates who would be arriving from well-developed countries. Among the cargo brought to Armenia from the United States, were the latest in American automotive and home appliance technology. While not many Armenian-Americans left for Armenia after World War II, there were two repatriation caravans from the United States. The first was in 1947, and the second caravan in 1949. The Antaramian brothers, Paul and Massey, were joined in Armenia by their parents, Asadour and Seranoush, and their two younger brothers, Anto and Perry, after their Wisconsin farm sold. Paul remembers the family bringing with them from the United States to Armenia, all types of construction and household supplies, tools and machines, including lumber, windows, door knobs, hinges, screws, wires, and nails with the intention of building a house. Their cargo also included washing machines, stove-oven ranges, refrigerators, a tractor, and a Nash Motors automobile called the Ambassador. Other Armenian-Americans also brought automobiles, such as the General Motors Buick and the civilian version of the “Jeep,” by Willys-Overland Motors. Deran Tashjian, Armenian Repatriate of 1949, originally from Watertown, Massachusetts, remembers his father bringing their Buick Roadmaster to Armenia. It was a car coveted by Soviet officials, who kept badgering Deran and his family to release the car to the government. Deran remembers how under threats of being exiled his family eventually relinquished the car to communist officials.

I have just begun my artistic journey of the postwar Armenian repatriation. From my visits thus far I have collected over 45 black and white photographic images of repatriate children and families taken in Armenia from 1947 to 1966. The photographs collected are to be complied in a database for my artistic interpretation as well as archival documentation. In a mélange of drawings, paintings, and installation art scheduled for exhibition in Spring/Summer 2013, the imagery will be used to interpret the cultural, social and economic situations of that period. I am also documenting short stories that narrate the circumstances and emotions of the people who experienced the events during this particular episode in Armenian history. Clearly, it is another facet of the social aftermath of the Armenian Genocide. I am interested in collecting more photographs and interviewing more people for their stories, so if you are a repatriate or know of a repatriate who may be interested in my project, please contact me at hazelantaramhof@yahoo.com, with “repatriate project” in the subject line. I would be pleased to discuss my project with you in greater detail.

To Top

To Top