Foto Luigi Lusenti

The Yugoslav dissolution wars are often considered a marginal chapter in European history, but the testimonies of many Italian citizens return the memory of conflicts that went far beyond the boundaries of the countries involved

When recalling Europe's recent history, Yugoslav dissolution wars are often forgotten, or recalled as the latest episode of violence in an ever-turbulent periphery of the continent. In European memory politics, Sarajevo peeks out on June 28th, 2014, centenary of the assassination that led to the outbreak of World War I. But the conflicts of the nineties – sometimes with the exception of the most tragic episodes such as the Srebrenica genocide – are struggling to find space in public commemorations, school curricula, or museum institutions.

However, recent research has shown how much the Yugoslav wars involved European public opinion and triggered a number of solidarity initiatives in several countries. Between 2013 and 2014, as part of the project "We were striving for peace", OBCT committed to reconstructing the engagement of Italian civil society in support of populations and to bring to light the memories of that experience, which are today preserved mainly at the individual level or in circumscribed settings. What emerges from the testimonies is a complex, multifaceted picture that opens up many issues. However, the overall choral narrative recalls in particular how much and how deeply Yugoslavia's conflicts were felt outside the countries involved, becoming part of the experience of many people in Italy and Europe.

A sea of relationships

A lot remains to be told on the relations between the two sides of the Adriatic in the second half of the 20th century. While the contrasts and tensions that characterised relations in some historical periods are often a matter of discussion – just think of the events of the upper-Adriatic border region – testimonies uncover a peculiar network of relationships and personal contacts.

The testimonies on the origins of the solidarity mobilisation of the nineties bring this network back to light: "At that time the Magistrala, the road that follows the coast from Trieste down, was very busy with vans, trucks of Italians carrying aids, perhaps through the contacts that existed before the war. It was one of the characteristics of the unique involvement of the Italians – many brought humanitarian aid to the people they knew, maybe from going on vacation there a year or years earlier".

While ties made by tourism come up in numerous stories, others are intertwined with political interest. An activist engaged from the early stages of the conflict gets emotional when telling: "The experience of Yugoslavia, with the construction of the movement of non-aligned countries, seemed to be a possible reference point for a different socialism, despite the shadows. So there was a fondness for Yugoslavia, which was partly human, because of the holidays, but also holidays came from this idea that Yugoslavia was a country to love".

Relationships resurface in the most diverse areas, such as those between twin towns dating back to the sixties. Another volunteer recalls: "Many of these relationships were born, in my opinion, more by chance than by ideology. For instance, Ancona and Split used to be twin-cities before the war; one of the first contacts to get mobilazed back then was Cgil, an Italian trade union which was twinned with a Split trade union. The people from Cgil went to Split and they were told to go south, to Makarska and Gradac". That is, to the first refugee camps.

The "war at home"

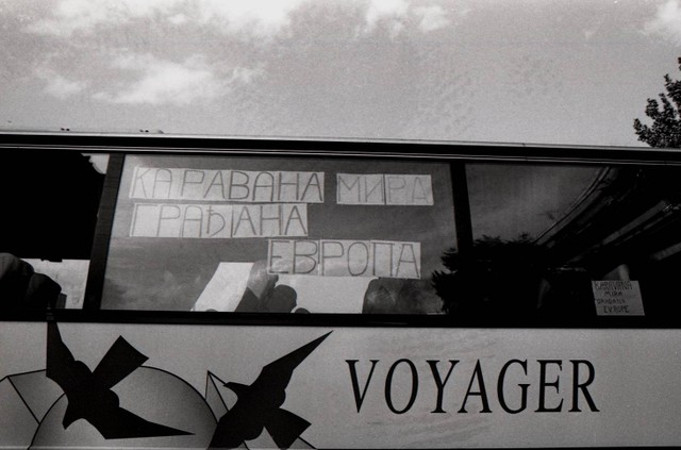

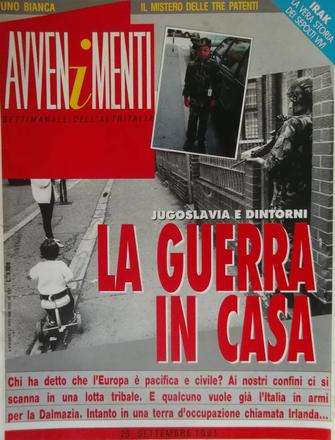

From the first days of fighting, the conflict in former Yugoslavia was perceived as a "war at home". The images that came live on TV in the homes of the Italians were recorded few miles away, producing an ever greater involvement in public opinion.

The testimonies recall a war experienced through a humanitarian attitude strengthened by geographical proximity: "For me it was inconceivable that children like mine, just because they were born on the other side of the Adriatic, had a destiny of misfortune", stresses a volunteer. Another explains: "I've always been pretty motivated in these things, I've always felt the urge to help others. But here there was more, because I was very attached, I had been in the former Yugoslavia, I had travelled there as a young man. So for me it could only be that way".

In addition, the impression was widespread that the events somehow concerned the whole continent: "I think the Yugoslav question really struck all of Europe. In the sense that the idea that a war in Europe had broken out after World War II, I believe, shook all people with a civil and political conscience and with a personal sensibility of a certain kind. So solidarity was huge. We also crossed a convoy that came from Scotland: they also brought humanitarian aid, a convoy of Scottish miners who remembered that aid and solidarity had come from Yugoslavia in Thatcher's dark times".

Driven by proximity, many approached the Yugoslav war conditioned by difficulties of interpretation, partial visions, and settled clichés of a distant, "other" world. The engagement of many Italian volunteers was affected by such approaches, but at the same time pushed many to deepen the knowledge of the territories beyond the Adriatic: "The thing that struck me so much – I had never been in Yugoslavia – was to find a people, people, very similar to us. Beyond the language and few other things. This impressed me. To see a war of that kind affecting those people".

Which Europe?

Direct engagement in the war context put many people in the position of confronting the supranational institutions active in the conflict. The "hour of Europe" had come, but the European community's response was far from effective. During the conflict, many people from different backgrounds and political convictions questioned the role and significance of European institutions and the political destiny of the continent.

Volunteers realised how urgent and serious were Europe's issues and inactivity: "Europe was still at that time, it just did not know how to move. In the sense that there were problems in Europe: France and England defended Serbia, Germany defended Croatia. So it was a European conflict rather than just of the former Yugoslavia".

Volunteers and activists questioned Europe's responsibilities in the conflict: "For me personally, there was a clear perception of how close they were to us, and how we too had responsibilities beyond Italy's history in Rijeka and Croatia. It was immediately clear that Europe was not prepared for such a thing – immediately giving the green light to the Republic of Slovenia seceding, the Vatican's intervention for Croatia, it was clear that there were big responsibilities".

At the same time, in many circles of mobilisation, confidence strengthened in grassroots international diplomacy: "All those young people that went there thriving on mere solidarity. They were all animated by wanting to reunite, rebuild relationships and communities. They were, I think, the only true Europeans. Europeans in the institutions either took somebody's parts or complied with international power games”.

The impact of this direct experience emerges from the interviews: "It seemed to me that "Europe as a concept" was there. I came back here with the feeling that I had been in Europe. The niche, the exception of well-being was here, while history's central place was there. We felt that the war would have dramatic consequences, that it could not but change the concept of Europe".

In some cases, this translated into an attempt to put pressure on European institutions, as recalled by an activist in favour of deserters who fled the conflict: "For the reception of conscientious objectors, we participated in a European forum and a collection of signatures, which was then submitted to the European Council in Strasbourg for the recognition of the right to conscientious objection in the republics of the former Yugoslavia". An attitude that found expression in Alexander Langer's commitment "Europe is born or dies in Sarajevo" .

The collected evidence suggests looking at Yugoslav wars from a wider perspective than we usually do. There is a collective memory of conflicts, nourished by experiences, biographies, ties that involved thousands of people and rarely find space in the public memory of those events. The violence and the drama of the conflicts of the nineties did not only shake the countries emerging from the Yugoslav dissolution, but also had a strong impact on many Italian and European citizens, that often translated into awareness and mobilisation at the international level.

Ricerche

- Marzia Bona (2016), "Gli anni Novanta: una rete di accoglienza diffusa per i profughi dell'ex-Jugoslavia ", Meridiana - Rivista di Storia e Scienze Sociali, n. 86.

- Marco Abram, Marzia Bona (2016), “Sarajevo. Provaci tu, cittadino del mondo. L’esperienza transnazionale dei volontari italiani nella mobilitazione di solidarietà in ex-Jugoslavia ", Italia Contemporanea, n.280.

- Marco Abram (2014), "I territori italiani nella mobilitazione civile per la ex-Jugoslavia: i caratteri dell'esperienza trentina", Archivio Trentino. Rivista interdisciplinare di studi sull'età moderna e contemporanea, n. 2.

- Christine Schweitzer (2014), "A European Anti-War Movement. The Response of European Civil Society to the Conflicts in the Former Yugoslavia", in Bettina Gruber (a cura di), The Yugoslav Example. Violence, War and Difficult Ways, Münster, Waxmann.

- Vesna Janković (2012), "International Peace Activists in the Former Yugoslavia. A Sociological Vignette on Transnational Agency", in Bojan Bilić, Vesna Janković (a cura di), Resisting the Evil. [Post-]Yugoslav Anti-War Contention, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaf.

This publication has been produced within the project Testimony – Truth or Politics. The Concept of Testimony in the Commemoration of the Yugoslav Wars, coordinated by the CZKD (http://www.czkd.org/ ) and co-funded by the Europe for Citizens programme of the European Union . The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.

To Top

To Top