Doboj, Bosnia and Herzegovina, May 2004 (© Dejan-Milosavljevic/Shutterstock)

Six years ago, Bosnia and Herzegovina experienced a catastrophic flood. Today the country remains among the most exposed in all of Europe. Efforts have been made to reduce these risks, but they are often limited to international projects, without local institutions really taking charge of them

May 2014. The "Tamara" low pressure area raged on the Balkan peninsula. In a few days a quantity of rain fell that had not been seen for 120 years. The mountains of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the country most affected together with Serbia, were affected by about a thousand landslides while flash floods descended from the steepest slopes. In a short time the waters swelled the Bosna, the Drina, the Vrbas, the main rivers of the north, and from there they headed towards the Sava, which should have conveyed them to the Danube and the Black Sea. But even the Sava was in the grip of an unprecedented flood. Unable to flow further, the water overwhelmed the densely inhabited valleys of the two countries. Farms, inhabited centres, factories, roads ended up underwater. Even minefields: an unknown number of devices were dragged elsewhere, to unknown and therefore more dangerous places. The flood would cost Bosnia and Herzegovina 25 direct casualties, and 15% of GDP. One million people would be affected, thousands of them would leave their houses.

Long coexistence with floods

The devastations of 2014 made it clear that tackling natural disasters should be a top priority. Yet, for the country, the destructive floods are certainly not new.

As anyone who has read "The Bridge on the Drina" – one of the country's symbolic novels – will remember, this was not the first time that the historical events of this land revolved around the changing moods of its rivers. The most serious flood before 2014 dates back to 1896, at the time of the Austro-Hungarian occupation. Since then, however, the floods have never stopped causing damage – at least five times in the 1900s. The 21st century started recently, but the bill is already high: in 2004, and especially in December 2010, serious damage was recorded. Things did not go down smoothly in 2019 either.

The frequency of floods in recent years appears to be in line with many studies on climate change, which for the region indicate a decrease in rainfall, but also an increase in extreme phenomena concentrated in a short time.

Although the Western Balkans are the scene of even more destructive events such as earthquakes, floods represent the most concrete risk. In fact, they occur more often and affect the most populated and most economically viable areas. According to a World Bank study, a major flood (with a 100-year turnaround time) would affect 14% of the country's population, causing damage equal to 14% of GDP. The average in the Western Balkans, although high, currently stands at around 10%.

The risk is not the same for everyone

Natural disasters are by no means "democratic": they affect some categories more than others. Both during and after the emergency, women are more exposed than men: more often at home, more often financially dependent on husbands, and burdened with the care of even more vulnerable family members. It is even worse for the disabled, minors, the elderly, and minorities such as the Roma – not to mention the many migrants currently in the country hoping to cross the borders of the European Union.

Bosnia has another exposed category – the people forcibly relocated after the war, in little or no planned settlements, and without large social networks to protect them. According to a UNDP report, in some municipalities even 100% of the families who lost their homes belonged to this category. In 2014, the condition of many people who already lived at the limit of the poverty line worsened further, accelerating the constant emigration from the country. Some consider them the first climatic refugees in Europe.

The two entities into which the country is divided are exposed to floods in very different ways. Republika Srpska, where production activities are concentrated in the valleys of the most restless rivers, and poorest in infrastructure, sees 6% of GDP at risk each year. The figure even rises to 20% for larger floods which, fortunately, are expected to occur once every 10 years.

A heavy legacy

As in most of Europe, the flood plains of the Balkan rivers – a natural relief valve for the floods – have been gradually swallowed up by concrete. For Bosnia, with the wild urbanisation and illegal construction that after the war led thousands of people to move to exposed areas, the situation is even more serious.

During and after the conflict, moreover, many defense works – embankments and canals, but also urban water control systems – and monitoring stations built in previous decades fell into disrepair, when they were not deliberately destroyed.

The Balkan rivers do not care about the international or internal borders that divide Bosnia into two entities and numerous cantons, realities with their own regulations. Fragmentation hampers a river basin-based approach, the only one effective in river management. This also affects the databases, which are essential for correctly assessing the risk. Often incomplete, they are dispersed in the myriad of local institutions or held by meteorological institutes in perpetual deficit, and therefore reluctant to share them for free.

Change of pace, in the footsteps of the European Union

Bosnia and Herzegovina, like its Balkan neighbours, has adhered to numerous international programmes and conventions for the mitigation of natural hazards – an approach that, at least in theory, shifts the focus from emergency to prevention and frames the problem in the wider context of sustainability. The most concrete frame of reference is the European Union: Bosnia and Herzegovina has adhered to the 2007 Flood Directive, and also the structure of the Bosnian Civil Protection, operational since 2008, follows that of the EU.

However, there are many obstacles between intentions and concrete action. Even more than economic and technical, the first problem seems to be cultural.

"Politics struggles to keep up with the current vision of sustainable development, and therefore implement the appropriate reforms, both economic and public sector", comments Almir Beridan, a legal consultant who deals with disaster reduction in South-Eastern Europe. "Good quality funding and data are tools that need to be used for more efficient state management".

To put a strategy into practice, you need a risk analysis, and to get it, you need detailed hazard maps. But to track them you need a good quality database, a certain number of collaborators, adequate financing – all things in short supply in the country.

Commitment should translate into concrete, lasting action: drills, training opportunities for staff, and the possibility of getting out unscathed from one of the most complicated bureaucracies in the world. Yet, according to many experts, administrators have failed to put prevention among the priorities.

Despite these difficulties, important results have been achieved. In 2012 and 2015 two fundamental documents were drawn up – an Assessment for Natural Risks, and a specific one for floods and landslides in the construction sector. An action plan was then drawn up to move from analysis to effective risk reduction.

Then there were some projects, aimed at specific river basins. The International Sava Commission has been dealing with the most important river in the Western Balkans since 2005 and has developed modern water monitoring systems and a flood management plan spanning over four countries.

On the Vrbas River, which flows through Jajce and the capital of Republika Srpska Banja Luka, a project under the auspices of the UN has led to modern monitoring networks, drills, and a management plan. Other similar current or recent initiatives concern other rivers, also shared with neighbouring countries.

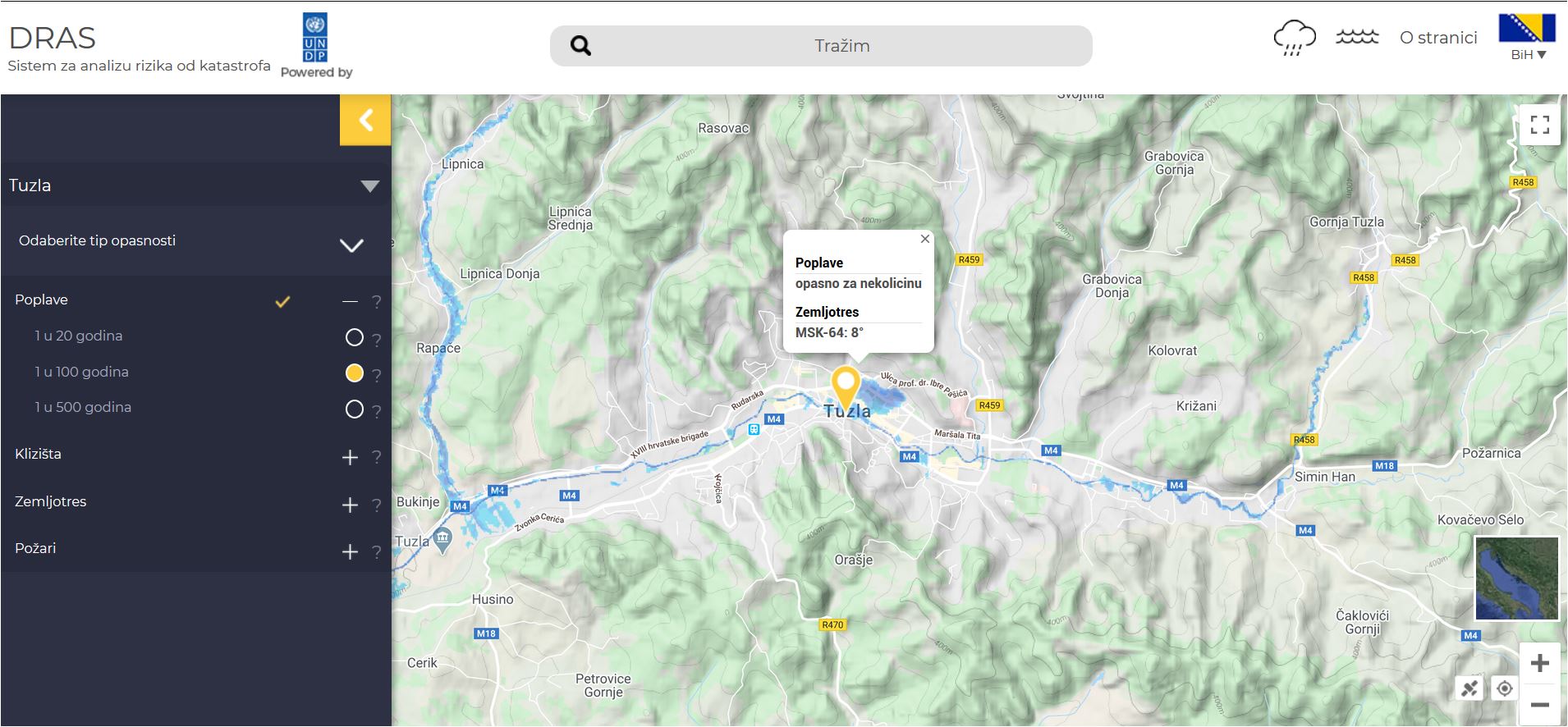

Then there is DRAS , an online information system for institutions and citizens: currently under expansion, it allows you to view risk maps and meteorological data in a very intuitive way.

Behind many of the results achieved there is the effort of institutions such as the UNDP – the UN programme for development – and international initiatives such as the DPPI , a project that seeks to harmonise the response to disasters in Southeast Europe. Funding also almost always comes from abroad, such as the 43.5 million Euros allocated by the European Union after 2014.

Until the country takes ownership, however, these promising projects risk remaining happy exceptions. International aid tends to focus on individual projects and cannot last more than a few years. If local authorities do not take up the task, its driving force is exhausted.

The situation in the country – endemic corruption and clientele, wild privatisations, and a constant reduction in services – certainly does not favour a climate of trust. The distance between the origin of the projects and the territories does not help either.

For their part, environmental NGOs have created an important movement in defense of the rivers and have little trust of the institutions that continue to allow a "tsunami" of new hydroelectric plants without batting an eye.

The Action Plan itself highlights that the efforts made are still not enough. Spatial planning, scholars say, should take on more importance and place more emphasis on risk assessment and management. Above all, it should be ascertained that it is actually followed. We should invest in technology and change urban planning laws, especially in Republika Srpska.

Raising awareness

With the coronavirus pandemic, the importance of risk management is as apparent as ever. The fallout from the emergency on civil protection mechanisms will most likely be huge, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Yet, there are still too many variables to predict what will change in terms of budget, staffing, and procedures.

Health emergency or not, it is about making choices, which depend on politics but are product of the country's cultural climate.

"The most important challenge for the future is to educate future generations about risks", adds Almir Beridan. "It is necessary that the public sector works, but that individuals too finally become aware of the importance of disaster mitigation and citizen involvement".

The crystal clear rivers are one of the best visiting cards of Bosnia and Herzegovina – the Neretva that flows to Mostar under the Old Bridge, the clear sources of the Bosna, the streams that make it one of the world's rafting paradises. There is no miracle recipe for zeroing the risk, but it can be managed in an intelligent way, according to criteria discussed and shared as much as possible within the country. Only in this way can the rivers of Bosnia be remembered for their extraordinary beauty and not for the pain caused by their floods.

To Top

To Top