Vondelpark, Amsterdam - fotoleren.nl

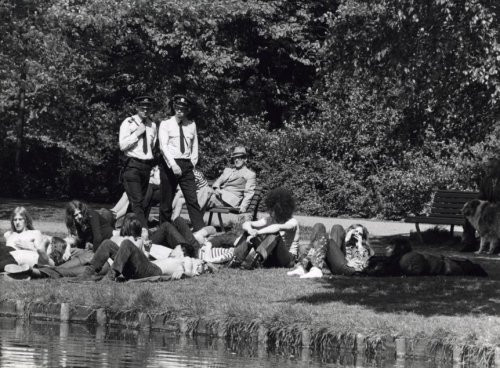

Vondelpark, a cult attraction for hippies from all over Europe. Azra went there too, along with Snježana, Cvele, Paja and Gorki who spent a summer there in the 70

As an adolescent, I managed to avoid the jobs that I detested at home - washing the windows, for example. But when I needed money to travel, for a week I would tirelessly wash all the windows of the Sarajevo trade union building – 60 metres long and two floors high. My friend Snježana and I wanted to go to Amsterdam together in the summer of 1973 and we earned the money we needed cleaning windows, a job we found through the Student Service which procured odd jobs for university students.

In Amsterdam we were heading for Vondelpark which, in the sixties and seventies, had become a cult meeting place for hippies and young people from all over the world. The right place for us – all flowers, peace, love and against any and everything. We often protested when we were young, not necessarily for real reasons.

In fact, for many of the youth in Yugoslavia the seventies and eighties were golden years. The universities and schools were excellent, open to everyone, and cultural life was flourishing. The same films and shows to be seen in western metropolises could also be seen by us in Yugoslavia. We read modern literature, listened to rock music and blues and could enjoy important exhibitions. Countless newspapers and magazines were published and novels and poetry translated.

But we were looking for something else, something which was later called “flower-power”, which for us meant absolute freedom, living in harmony with others and nature. And, according to an opinion which was widespread among the youth, to reach this you had to travel abroad.

Snježana, Cvele, Paja and Gorki

Snježana was the one to suggest Vondelpark. She was more informed and thought up our adventure. We saw each other in various cultural circles, participated in meetings and discussions, but she often finished by saying: “Yes, but this is nothing. We have to go abroad, to the west”. She was one of those talented people, who was successful at anything she tried, with well above average results. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, was an exceptional painter, but would have been an equally good poet or writer. Her parents were as rigid and ordinary as she was open and original.

Five hundred kilometres to the east, in Belgrade, three student friends, Cvele, Paja and Gorki, were saving up for the summer trip. Through the Student Service they too had a job they considered a gold mine. Periodically the government had to stock supplies for the national reserve – among other things tons of sugar were sent to a warehouse near Belgrade where Cvele, Paja and Gorki unloaded the sacks from the containers and stacked them.

Later, when we met them at Vondelpark, they told us how they carried out the job: the sacks of sugar were of different weights depending on where they came from – from Hungary they weighed 80 kilos, from Yugoslavia 50 and those imported from Cuba 100. Paja and Gorki took a sack, one at each end, and loaded it onto Cvele's back, so he “built” castles of sacks. They earned a thousand dinars a day. “We spent ten days working, then ten days getting our backs straight again” they said, laughing like mad as if they were telling a joke.

Hitch-hiking

Snježana and I had caught the bus from Sarajevo to Slavonski Brod, the Croatian town near the Highway of Brotherhood and Unity (Bratstvo i Jedinstvo), travelled by many cars in both directions, towards Western Europe or towards the Middle East. We were convinced it wouldn't be difficult to continue our journey hitch-hiking from there. In fact the people who gave us lifts were enthusiastic and I felt they appreciated what we were doing. Often as we chatted along the way most people agreed with our opinions, liked our choice and approved of our disobedience.

We could easily have paid for the journey ourselves - on that occasion it wasn't a question of money, but at that time for young people, hitch-hiking was the rule. Even our way of travelling was a demonstration of our choices, consistent with the ideology of the youth of the time, opposed to institutions, to formal culture, to the politicians, to market forces, against nuclear weapons and against war.

Vondelpark

We got there in two days, dirty, with crumpled clothes, greasy hair, grey-green backpacks bought at at deposits of military rejects: we were in perfect harmony with the other youth who thought like us and were meeting at Vondelpark.

The park was nice and big, with an artificial lake, trees and wide stretches of grass. Built in the eighteenth century, it must have been an elegant place in the English style, but in the seventies it had been “taken over” by young people resolved to change the world. Finally we were at the place where we imagined we would find total freedom. But freedom is not something instinctive or automatic. In that month spent in Vondelpark I understood that, to be free, you needed to have courage, be aware and able to manage your freedom.

In our country there was the family or the state that thought for us and organised everything, or nearly everything, for us. During the first days Snježana and I wandered around, naively, here and there, without knowing what to do, approaching groups to listen to music or what was being said, watching what the others did; but we were still alone.

One morning while I was queuing to wash I heard someone speaking “our” language, that is Serbo-Croatian. Turning round I saw the three boys – tall, thin, with long uncombed hair and scruffy beards. “Hey, are you ours?” I asked. Once upon a time all we Yugoslavs thought of ourselves as “ours”, in the sense of fellow-countrymen, friends, relatives. We then, in the nineties, became bitter enemies. Today when I hear someone speaking “our language”, I'm careful not to reveal my identity. First I have to check from which of the ex Yugoslavian republics he/she comes to see if we are “ours” or enemies.

I liked those three straight away. Students from Belgrade: Cvele was of Bosnian origin, studying philosophy, Gorki engineering from Split (his father had named him after Maxim Gorky, the Russian writer and teacher), while Paja was from Čačak, a Serbian provincial town and he was studying medicine.

I introduced them to Snježana and saw that they were fascinated by her. They proposed we stay together, that is that we transfer to their camp. Snježana hesitated: “Not with ours, we're here to meet people from other parts of the world”, she whispered; but then she gave in and we went to camp with the guys from Belgrade.

The camp

Our group's position was a bit off centre, among the trees. The Belgraders were well organised with sleeping bags, a camping stove and a guitar. “Our group”, so to speak. Nothing was fixed or considered property – everything was in common. There was a continuous coming and going – some would sit down to chat or eat with us, some would stay to take part in discussions, some would lay out their things next to ours. And sometimes one of our group would go off and come back in the evening or the following day.

Our days were spent eating, drinking, sun-bathing stretched out on the ground, singing, listening to music, taking part in discussions about world affairs; and there was a lot of grass. They offered it to you and you shared it.

One day while we were discussing oriental philosophy, all sitting on the ground in a haze of smoke of grass, we saw two policemen coming in our direction. We stopped the conversation and turned towards them, waiting in silence to see what would happen. Nothing. They were two local students who, during the summer, had a kind of security role, like traffic wardens. They wanted to smoke grass – they knew we had it and they could get it free.

The hippy movement was not just grass, a useless, superficial whim. Our month of apprenticeship in Vondelpark does not represent it well either in form or in substance. Both the style and values have had a considerable impact on our culture; they had an influence on pop music, television, literature and art in general all over the world. Since the sixties many aspects of the hippy culture have become common dominion.

Returning

Paja was the first to leave – he had to study for a very difficult exam in anatomy. Then, from the world of “absolute freedom”, Gorky decamped with his guitar – before the beginning of term he had to spend a bit of time with his family in Split.

At the end of July it began to rain, turned cold and it wasn't much fun sleeping out of doors. Cvele had toothache, Snježana and I had to go home. We three went back together, hitch-hiking, naturally. We soon reached Cologne in Germany. Outside the town a fellow with a jeep stopped just to take us where he said it would be easier to get a lift, and in fact a lorry soon picked us up, all three in the cabin. The driver was German and I remember his nineteenth century moustache and red cheeks.

He didn't understand a word of English, French or Russian, the languages we three spoke. Whatever we said he smiled and nodded his head. Out of desperation I started listing a string of German words we used in Bosnia, as if they were ours, usually with the wrong pronunciation or change of meaning: rajsferšlus, špajz, špenadla, zihernadla, rolšuhe, drajfirtel, gojzerice, luster, nahtkasna. The German nodded at first, then understood the game and began to laugh out loud, bending forwards and backwards laughing louder and louder. We were scared stiff that he'd lose control of the lorry. Then he calmed down and raised his thumb to show he'd understood. With the help of hand signals we managed to tell him where we were going. Yes, he confirmed. Ok, he had understood. But first he would take us home, a farm near the German town of Essen, where his wife and three children, two boys and a girl, welcomed us with open arms.

We stayed there a whole week, without knowing their language. The family had an apple orchard, a small vegetable garden and poultry. Our hosts looked after us as if we were their own children, and for us that week was a kind of breathing space, after a month at Vondelpark, with its intense intellectual activity, protests, songs against war and in favour of peace, debates on how to set the world to rights, and, above all, sleeping on the ground.

Snježana painted portraits of their three children, Cvele got busy cooking, showing our hosts how to make the Bosnian mainstay - pita, and I helped the mother with little household chores. After a week the lorry driver, who had meanwhile been away another three days, took us back on his lorry, leaving us at a place where we could get a ride in the direction of home.

In two days we were in Zagreb. We were discussing how to go on, whether by train, bus or hitch-hiking, when Cvele noticed his tooth wasn't hurting any more. “You see, internationalism is harmful”, Snježana said ironically. “Better to stay in your own country”. We all burst out laughing. Not just for the joke - it was good to be back home again.